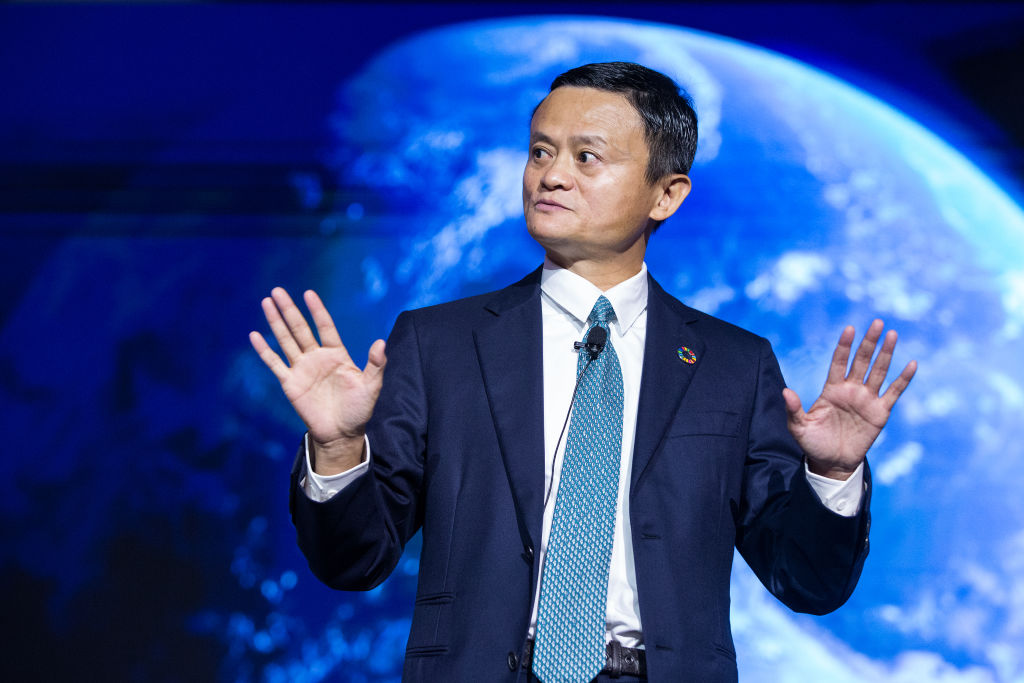

When China’s leader Xi Jinping late last year quashed Ant Group’s initial public offering, his motives appeared clear: He was worried that Ant was adding risk to the financial system, and furious at its founder, Jack Ma, for criticising his signature campaign to strengthen financial oversight.

There was another key reason, according to more than a dozen Chinese officials and government advisers: growing unease in Beijing over Ant’s complex ownership structure—and the people who stood to gain most from what would have been the world’s largest IPO.

In the weeks before the financial-technology giant was scheduled to go public, a previously unreported central-government investigation found that Ant’s IPO prospectus obscured the complexity of the firm’s ownership, according to the officials and government advisers, who had knowledge of the probe. Behind layers of opaque investment vehicles that own stakes in the firm are a coterie of well-connected Chinese power players, including some with links to political families that represent a potential challenge to President Xi and his inner circle.

Those individuals, along with Mr. Ma and the company’s top managers, stood to pocket billions of dollars from a listing that would have valued the company at more than $300 billion.

During his eight years as president, Mr. Xi has sidelined many of his rivals, and his hold on power now compares to that of Mao Zedongr.

His initiatives have included campaigns against corruption, real-estate speculation and other high-risk financial activities. Mr. Xi has used the antigraft crusade to target both actual corruption as well as to strengthen his own hold on power. Ant’s IPO plan represented the kind of payday and accumulation of wealth that Mr. Xi has long frowned on.

An Ant spokesman said in a statement that the details of Ant’s shareholding structure were fully disclosed in the group’s prospectus and in its public business registration records.

Before the probe, regulators at the central bank were already worried about Ant’s business model. The company owns a mobile payments app called Alipay that is used by more than a billion people. It gives Ant voluminous data on consumers’ spending habits, borrowing behaviors and bill- and loan-payment histories, which the company has used to build a financial-services giant.

It has made loans to close to half a billion people, operates the country’s largest money-market fund and sells scores of other financial products. But it hasn’t had to follow the tough regulations and capital requirements that commercial banks are subject to. It makes profits from the transactions, while state-owned banks supply the majority of the funding and take on most of the risk.

“On one hand, you got a bunch of individuals potentially amassing large amounts of wealth,” one of the people familiar with the probe into the shareholders said. “Then on the other hand, much of the risk has been transferred to the state side.”

In a late-October speech, Mr. Ma harshly criticized regulators for rules he said were unnecessary and held back technology innovation. He infuriated top financial officials—some of whom were in the room for the speech.

The public blast of the state’s regulatory powers, coupled with the investigation into Ant’s ownership structure—which had started even before Mr. Ma’s speech—formed the basis for Mr. Xi’s decision to shut down Ant’s IPO and force the company to scale back lending and other banklike services, according to the people familiar with the probe.

Mr. Xi at the same time launched a campaign to rein in China’s technology sphere overall to prevent big firms like Ant from using their size and their troves of consumer data to engage in anticompetitive practices.

The moves indicate that after years of using a light hand with tech entrepreneurs, Mr. Xi is making greater demands for them to be aligned with the political priorities of the day.

Alarm bells

Some of Ant’s investors and the way their stakes were structured set off alarm bells as regulators dove into the details of the prospectus, the people familiar with the investigation said.

One is Boyu Capital, a private-equity firm founded in part by Jiang Zhicheng, the grandson of former Chinese leader Jiang Zemin. Many of Mr. Jiang’s allies have been purged in Mr. Xi’s anticorruption campaign, though he remains a force behind the scenes.

Another stakeholder with ties to Mr. Jiang, part of what is called the “Shanghai faction,” is a group led by the son-in-law of Jia Qinglin, a former member of the Politburo Standing Committee, the top echelon of the Communist Party.

Other backers seen as problematic include a real-estate developer who benefited from peer-to-peer lending schemes years earlier—schemes that nonetheless caused scores of investors to lose their life savings when they went bust, the people familiar with the probe said.

Mr. Ma’s connection with Jiang Zhicheng, a Harvard-educated “princeling,” as the offspring of China’s leaders are called, goes back to the years when Mr. Ma was expanding Alibaba Group Holding Ltd., the e-commerce giant that is the source of his wealth as one of China’s richest people, and that eventually spawned Ant Group.

In 2012, the younger Mr. Jiang, also known as Alvin, helped Mr. Ma negotiate a deal to buy out half of Yahoo’s stake in Alibaba. A consortium of investors consisting of Mr. Jiang’s Boyu, China Investment Corp., and the private-equity arms of China Development Bank and Citic Group, all with strong political ties, financed part of the $7.1 billion needed. The nearly 5% stake in Alibaba the consortium received in return soared in value when the company listed on the New York Stock Exchange two years later.

Boyu became one of the early investors in Ant in 2016—although this time in a more roundabout way. Its base in Hong Kong was a potentially sticky issue at a time when Chinese regulations restricted “offshore,” or outside the mainland, ownership of payment services, a core part of Ant’s business.

According to commercial records viewed by The Wall Street Journal, Boyu first set up a subsidiary in Shanghai, which invested in a Shanghai-based investment firm. That firm then invested in a private-equity firm called Beijing Jingguan Investment Center, which in turn bought shares in Ant.

Beijing Jingguan is listed as one of 16 investors that provided a total of 29.1 billion yuan, or about $4.5 billion, to Ant in 2016. It also joined another group of funds that invested 21.8 billion yuan in Ant in 2018. Both investments gave Beijing Jingguan a nearly 1% stake in the company, according to Ant’s IPO document, putting it among its top 10 shareholders. The prospectus doesn’t mention Boyu’s involvement with Beijing Jingguan.

Mr. Jiang and other Ant investors mentioned in this article declined to comment.

Another stakeholder behind layers of investment vehicles is Beijing Zhaode Investment Group, controlled by Li Botan, the son-in-law of Mr. Jia, the former Politburo Standing Committee member with strong ties to Jiang Zemin.

Among China’s business and political elites, Mr. Li is best known for having helped establish in 2009 the Maotai Club, a private club in a historic house near Beijing’s Forbidden City that had been a haunt for princelings and their patrons until recent years.

Since he took power in late 2012, Mr. Xi has directed his ire at corruption in the party and the tales of members’ lavish banquets and harems of mistresses that had turned ordinary Chinese into cynics. Events like those held by Mr. Li’s Maotai Club were seen by the leader as harmful to the party. “You people, you either eat and drink yourselves into the grave, or die between the sheets,” he said at a meeting with senior officials earlier in his tenure, according to people briefed on the remarks.

Mr. Xi had little interest in having the Ant IPO funnel enormously lucrative financial stakes to well-known Chinese princelings, the people familiar with the probe said. For the leader, that could only widen the income gap and hurt his initiative to reduce poverty.

‘Red capitalist’

To fend off growing regulatory pressure as Ant became bigger, Mr. Ma made stakes in Ant available to an array of state stalwarts such as the national pension fund and China Investment Corp., the country’s massive sovereign-wealth fund, as well as its largest insurers.

Having such “strategic investors” on board—all poised to profit from the IPO—helped Ant’s stock-listing application sail through various levels of securities regulators last summer, the people familiar with the matter said. The application was approved in a month.

“Jack is very politically savvy,” said Gary Rieschel, a venture capitalist who helped manage Softbank’s investments in Asia in the early 2000s. “But if he hadn’t made them all rich, that wouldn’t have mattered.”

Over the years, with the political connections he garnered, Mr. Ma had become one of the most prominent of the “red capitalists”—tycoons with strong links to rulers—that have been a fixture of Communist reign in China.

For instance, after the 1949 takeover, the party turned to wealthy industrialist Rong Yiren to get the war-torn nation back on its feet. Giving business magnates some leeway and support also has worked in Beijing’s favour. Soon after China started to revamp its planned economy in the early 1980s, Liu Chuanzhi founded what is now Lenovo Group, the world’s largest maker of personal computers, with a loan from the government.

Mr. Ma, 56 years old, started Alibaba in 1999 in his apartment in Hangzhou, the capital of economically vibrant Zhejiang province. Softbank’s chief executive, Masayoshi Son, famously invested $20 million in Alibaba after a short meeting with Mr. Ma a year later. “I could smell him,” Mr. Son, known as a risk taker driven by instinct, recalled in a public talk in 2019. “We’re the same animal.”

The value of Zhejiang’s entrepreneurialism wasn’t lost on Mr. Xi, who ran the province from 2002 to 2007 and encouraged companies like Alibaba to expand.

Freewheeling finance

Some backers found among the layers of Ant’s shareholders highlighted the freewheeling attitude to internet finance, or fintech, the people with knowledge of the probe said. One was the real-estate developer Wang Xiaoxing, who raised funds from peer-to-peer lending firms that regulators say channelled the life savings of some mom-and-pop investors into high-risk financing schemes.

When those lending schemes went bust in the past few years, Ms. Wang found her way to invest in Ant through a private-equity fund set up by China International Capital Corp., or CICC, a leading Chinese investment bank.

Some of Mr. Ma’s longtime friends also gained stakes in Ant through various investment vehicles. They include some of China’s wealthiest individuals, such as property tycoon Lu Zhiqiang; Shi Yuzhu, chairman of the online gaming firm Giant Interactive; and Guo Guangchang, co-founder of Fosun International Ltd.

Mr. Guo’s Fosun, along with several other highflying private companies that took out large loans to finance overseas buying sprees, landed in hot water a few years ago for taking on too much debt. Regulators launched a series of investigations that curtailed the companies’ ability to borrow, shaking China’s business elite.

At a Beijing forum on Oct. 24—the same day Mr. Ma made his critical remarks at a Shanghai venue—Pan Gongsheng, a deputy governor at the People’s Bank of China, hinted at concerns over the nature of Ant’s owners.

“Some nonfinancial companies have blindly expanded into the financial industry,” Mr. Pan said, according to a transcript of his speech at the forum hosted by the prestigious Peking University. “Their shareholding structure and organizational structure are complex, and there are even prominent problems such as cross-shareholding, false capital injection and huge capital extraction,” he added.

Mr. Pan’s remarks were aimed squarely at Mr. Ma’s Ant, people close to the central bank said.

“Shareholding structure is one reason why we need to regulate firms like Ant,” an official at the central bank said.

For years, the kind of innovation Mr. Ma brought into the Chinese economy was in line with the leadership’s goal of turning China into a tech powerhouse. In recent years, Alibaba has also ventured into artificial intelligence and cloud computing, both deemed as key to China’s future.

There was some grumbling among officials in 2014 that Mr. Ma took Alibaba’s listing to New York, but the political environment was still encouraging, as evidenced by official moves to liberalize China’s currency and boost stock investing.

In 2015, that changed. Chinese stock markets crashed as a slowing economy popped a debt-financed stock boom. In the years since, the policy pendulum has shifted in favour of the state sector.

Mr. Ma had planned to list Ant on the new tech-oriented STAR Market in Shanghai, along with the market in Hong Kong, in an effort to please top leadership, according to people close to the company. The STAR Market was developed at the behest of Mr. Xi to create a Chinese stock market for tech firms that would rival Nasdaq.

The gesture did little to ease officials’ concerns about the billionaire’s plans.

Ant will now be restructured mainly as a financial firm subject to the kind of capital requirements applied to banks. The more stringent rules mean the firm may have to raise funds to beef up its capital base, opening a door for big state banks or other types of government-controlled entities to buy stakes. Existing shareholders’ stakes could be diluted as a result.

Ant’s key shareholders, senior managers and directors are also expected to be vetted by financial regulators, who will focus on examining their qualifications and sources of capital.

The officials close to the probe said it would take some time for Ant’s restructuring to be completed. “Whether the company can revive its IPO or not is not within the scope of the high-level government agenda right now,” one of the officials said.

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide.

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide.