As Generation X Approaches Retirement, Reality Still Bites

The ‘forgotten generation,’ born between 1965 and 1980, launched their careers at the start of a massive shift in how Americans work.

The ‘forgotten generation,’ born between 1965 and 1980, launched their careers at the start of a massive shift in how Americans work.

The oldest members of Gen X are turning 60 next year. Many can’t afford to stop working any time soon.

Born between 1965 and 1980, Gen Xers launched their careers at the start of a massive shift in how Americans work. Companies moved from pensions that promise steady income after years of service, to plans such as 401(k)s that place employees’ retirement destiny in their own hands.

Some Gen Xers were hit hard in their prime working years during the 2008 financial crisis. Others are still paying off student debt. Their children are increasingly living at home well into adulthood, while their own aging parents often require care. Few believe they can rely on Social Security to make ends meet later in life.

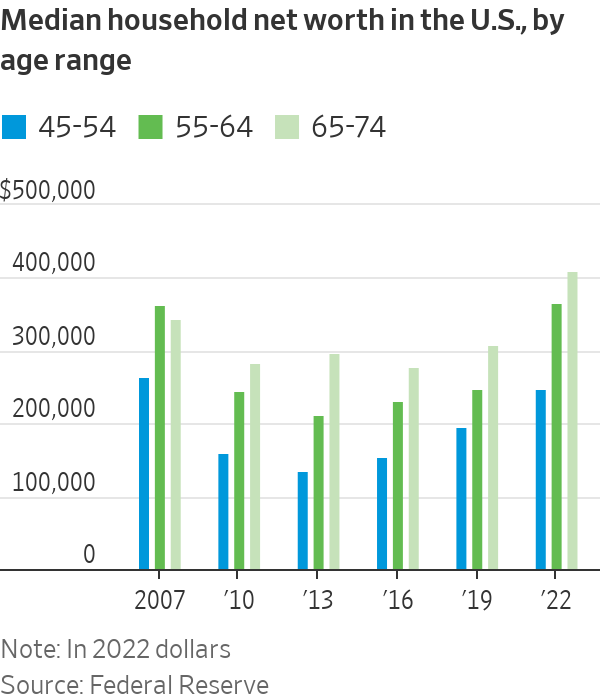

By some measures, Gen Xers are worse off financially than their baby boomer predecessors. The median household net worth of Gen Xers between 45 and 54 years old was about $250,000 in 2022, about 7% lower than that of baby boomers at the same age in 2007, according to inflation-adjusted Federal Reserve data. That was the only age group that experienced a drop in median wealth over the 15-year period.

David Bryan, 55, earns about $35,000 a year as a school-bus driver and lives on Tybee Island, Ga. He doesn’t own property and has about $100,000 in retirement savings from his previous jobs as a railroad conductor and a researcher at a college foundation.

It’s a different life than that of his parents, who worked for decades for the sheriff’s department and the post office and received steady pension checks when they retired.

“As long as my body will let me, it’s better I keep working,” said Bryan.

The roughly 65 million Americans in Gen X are sometimes referred to as the “forgotten generation,” sandwiched between the larger and louder baby boomer and millennial generations. They are also called the “latchkey generation,” often coming home from school as children to an empty house. Goldman Sachs Asset Management in a recent report called Gen X the “‘401(k) experiment’ generation.”

For decades, employers often supported loyal workers in old age through traditional pensions with set payouts for life. The advent of the 401(k) system pushed the responsibility on to the individual—and Gen X was caught squarely in the transition.

“Gen X is the first generation where they were mostly expected to figure out their retirement on their own,” said Jeremy Horpedahl , an economics professor at the University of Central Arkansas and director of the Arkansas Center for Research in Economics.

The early champions of the 401(k) never thought that it would become the dominant way most Americans save for retirement. It is named for a line in the tax code changed in 1978 that gave executives a tax-free way to defer compensation from bonuses or stock options. Human-resources executives and economists jumped on the 401(k) as a way to encourage saving for rank-and-file employees.

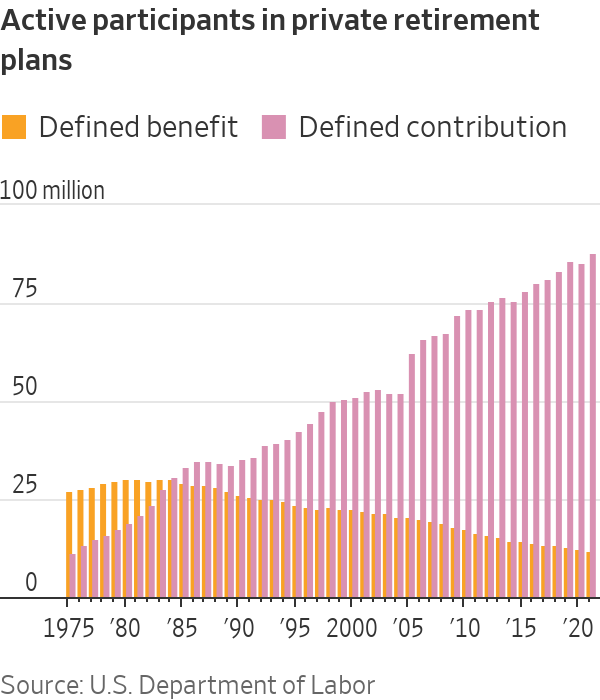

By the mid-1980s, the number of active participants in defined-contribution retirement plans—such as 401(k)s—overtook those in defined-benefit plans—such as traditional pension plans—in the private sector. Now, private pensions are rare.

When Gen Xers entered the workforce, the 401(k) was a new concept. Features such as automatically enrolling employees in a workplace plan and automatically increasing contributions every year didn’t become commonplace until later.

Other common private retirement savings tools were also introduced in the last half-century. The individual retirement account—a tax-deferred investment vehicle—was authorised in 1974, while the Roth IRA—funded with posttax money, but tax-free when withdrawn—was established in 1997.

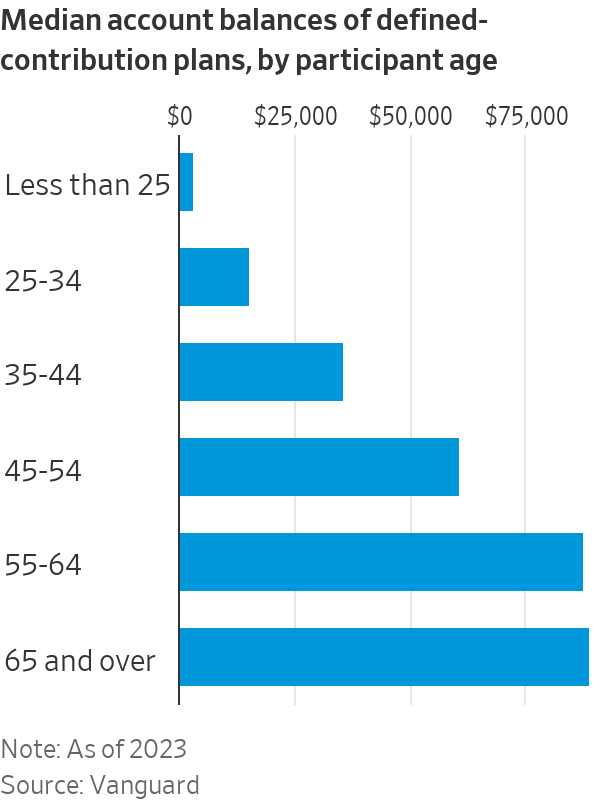

Gen Xers between 45 and 54 years old had a median account balance of roughly $60,000 in defined-contribution retirement plans at Vanguard Group in 2023, according to the firm. For most Americans, that is well below the target some financial experts recommend of having roughly six times one’s salary saved for retirement by age 50.

John Kotrides, a 54-year-old living near Charlotte, N.C., had contributed to 401(k)s ever since he started his career in banking about three decades ago. But whenever he moved to a different employer, he usually cashed out his 401(k) because there was a more urgent expense, such as a home repair or moving costs.

Keeping the money invested in the stock market didn’t seem worth it after witnessing crashes like the bursting of the dot-com bubble. Retirement seemed far away.

“You no longer have a generation of people whose employer took you from your first job into your retirement,” he said. “When we were offered 401(k)s, I don’t think that was a great deal.”

Kotrides says he doesn’t have much in retirement assets, besides the home he owns, where he lives with his wife and two daughters, who are 12 and 20 years old. After quitting his job as a mortgage lender during the pandemic, he now works as a bartender part-time and earns most of his money making social-media content, mostly nostalgic videos about the 1970s through 1990s. He likes having more time to spend with his family.

“This is basically my retirement plan,” he said. “I truly assume that I’ll continue to work to provide for my family as long as I need to.”

Even those who have benefited from the 401(k) system say it hasn’t been easy.

Scott Zibel, a 56-year-old in Leominster, Mass., started putting money in a 401(k) when he began working at a grocery store at 15. His father encouraged him to contribute. The account grew as he continued working at the store through college and became a manager. In his early 30s, he became an English teacher and expects to receive a pension after retiring.

When the stock market crashed in 2020 at the onset of the Covid pandemic, he and his wife pulled the money in his wife’s 401(k) out of the market and into a money-market fund. Now they have reinvested the money, but put a greater portion of it into bonds than before.

“I’m grateful for the 401(k), but there’s no guarantees as well,” he said, estimating his household retirement savings at a little over $1 million.

Zibel feels prepared for retirement but says he has to live frugally to save. He has driven the same car for 12 years and has avoided pricey expenses such as new carpeting for his 30-year-old home.

“My wife and I have done so much planning for the future with our money, it’s made living in the now difficult,” he said.

For some Gen Xers, the 2008 financial crisis was a hit that took years to recover from.

Around 2007, Darling “Diva” Moore was at the peak of her career as a managing partner at a title company in West Palm Beach, Fla. Then the housing market collapsed and her company went under. She couldn’t make rent on her apartment and had to crash with her significant other at the time, sometimes turning to sleeping on the beach or in the car.

“The Great Recession changed everything for us,” said Moore, who is 57. “After that, I don’t know how many Gen Xers trusted that system.”

After settling in Denver, more than two years went by before she landed a new job. She went back to school, getting an online bachelor’s degree in business management and master’s degree in human relations and organisation development. Now she is self-employed as a career counsellor.

As she is approaching her 60s, Moore is trying to locate money she contributed to various 401(k)s from jobs earlier in her career. Whenever she switched jobs, she didn’t rollover her balance to an IRA or new 401(k), so those accounts are scattered across plan providers. “In the ‘90s, they didn’t make it easy to find out where that money is,” she said.

She is also contending with student debt from a for-profit associates-degree program she completed in her 20s that has swelled to nearly $90,000 from around $27,000 due to interest.

More than a quarter of U.S. households led by Gen Xers between the ages of 45 and 54 had education loans in 2022, compared with about 15% of baby boomers at the same age in 2007, according to Fed data.

Soaring tuition costs, sky-high rents and other inflationary pressures for Gen Z are also Gen X’s problem. Many Gen Xers have forked over tens of thousands of dollars for their children to attend college. Young people are also increasingly living with parents, or relying on them for financial support, well into adulthood .

Pamela Likos’s 21-year-old son lives at home with her in the suburbs of Madison, Wis., while another son and daughter are at college.

“My kids are still definitely not grown and flown,” Likos said.

Some Gen Xers are simultaneously caring for aging parents, who are living longer than previous generations.

Likos isn’t in that situation yet, but her stepmother, who has Alzheimer’s, and her father are in their 80s.

“I need my parents to hang on healthwise for another five to 10 years because we are not ready to help financially, really,” she said.

Likos, who is 54, was the first person in her family to go to college, but didn’t work for about two decades after she got married and became a stay-at-home mom. When she got divorced about seven years ago, she found herself with no savings of her own and no resume to apply for jobs. She got a license to work as an esthetician for a few years and now is remarried. From her divorce, Likos received about half of her ex-husband’s 401(k), which comprises most of her plan for retirement.

The youngest members of Gen X are in their mid-40s, offering more time to boost savings ahead of retirement. Tyler Bond, the research director at the National Institute on Retirement Security, wonders if there will be diverging retirement experiences between the older and younger ends of the cohort.

“The older Gen Xers simply may not have time,” he said.

Avery Nesbitt, a 44-year-old operations manager in the Atlanta area, isn’t waiting for retirement to go on nice vacations or buy a new car because he wants to enjoy them now—and he doesn’t expect to be able to save up a cushy nest egg for later in life. If the Covid pandemic taught him anything, it was that anything can happen.

He and his wife have contributed modestly to employer-sponsored retirement accounts but didn’t feel like they could afford to save more. They own a home, where they live with their two children. That makes up the bulk of their wealth. He said he has put more money into life-insurance policies than in retirement accounts.

“I fully expect to work until I die,” Nesbitt said. “It is what it is.”

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

What a quarter-million dollars gets you in the western capital.

Alexandre de Betak and his wife are focusing on their most personal project yet.

Multinationals like Starbucks and Marriott are taking a hard look at their Chinese operations—and tempering their outlooks.

For years, global companies showcased their Chinese operations as a source of robust growth. A burgeoning middle class, a stream of people moving to cities, and the creation of new services to cater to them—along with the promise of the further opening of the world’s second-largest economy—drew companies eager to tap into the action.

Then Covid hit, isolating China from much of the world. Chinese leader Xi Jinping tightened control of the economy, and U.S.-China relations hit a nadir. After decades of rapid growth, China’s economy is stuck in a rut, with increasing concerns about what will drive the next phase of its growth.

Though Chinese officials have acknowledged the sputtering economy, they have been reluctant to take more than incremental steps to reverse the trend. Making matters worse, government crackdowns on internet companies and measures to burst the country’s property bubble left households and businesses scarred.

Now, multinational companies are taking a hard look at their Chinese operations and tempering their outlooks. Marriott International narrowed its global revenue per available room growth rate to 3% to 4%, citing continued weakness in China and expectations that demand could weaken further in the third quarter. Paris-based Kering , home to brands Gucci and Saint Laurent, posted a 22% decline in sales in the Asia-Pacific region, excluding Japan, in the first half amid weaker demand in Greater China, which includes Hong Kong and Macau.

Pricing pressure and deflation were common themes in quarterly results. Starbucks , which helped build a coffee culture in China over the past 25 years, described it as one of its most notable international challenges as it posted a 14% decline in sales from that business. As Chinese consumers reconsidered whether to spend money on Starbucks lattes, competitors such as Luckin Coffee increased pressure on the Seattle company. Starbucks executives said in their quarterly earnings call that “unprecedented store expansion” by rivals and a price war hurt profits and caused “significant disruptions” to the operating environment.

Executive anxiety extends beyond consumer companies. Elevator maker Otis Worldwide saw new-equipment orders in China fall by double digits in the second quarter, forcing it to cut its outlook for growth out of Asia. CEO Judy Marks told analysts on a quarterly earnings call that prices in China were down roughly 10% year over year, and she doesn’t see the pricing pressure abating. The company is turning to productivity improvements and cost cutting to blunt the hit.

Add in the uncertainty created by deteriorating U.S.-China relations, and many investors are steering clear. The iShares MSCI China exchange-traded fund has lost half its value since March 2021. Recovery attempts have been short-lived. undefined undefined And now some of those concerns are creeping into the U.S. market. “A decade ago China exposure [for a global company] was a way to add revenue growth to our portfolio,” says Margaret Vitrano, co-manager of large-cap growth strategies at ClearBridge Investments in New York. Today, she notes, “we now want to manage the risk of the China exposure.”

Vitrano expects improvement in 2025, but cautions it will be slow. Uncertainty over who will win the U.S. presidential election and the prospect of higher tariffs pose additional risks for global companies.

For now, China is inching along at roughly 5% economic growth—down from a peak of 14% in 2007 and an average of about 8% in the 10 years before the pandemic. Chinese consumers hit by job losses and continued declines in property values are rethinking spending habits. Businesses worried about policy uncertainty are reluctant to invest and hire.

The trouble goes beyond frugal consumers. Xi is changing the economy’s growth model, relying less on the infrastructure and real estate market that fueled earlier growth. That means investing aggressively in manufacturing and exports as China looks to become more self-reliant and guard against geopolitical tensions.

The shift is hurting western multinationals, with deflationary forces amid burgeoning production capacity. “We have seen the investment community mark down expectations for these companies because they will have to change tack with lower-cost products and services,” says Joseph Quinlan, head of market strategy for the chief investment office at Merrill and Bank of America Private Bank.

Another challenge for multinationals outside of China is stiffened competition as Chinese companies innovate and expand—often with the backing of the government. Local rivals are upping the ante across sectors by building on their knowledge of local consumer preferences and the ability to produce higher-quality products.

Some global multinationals are having a hard time keeping up with homegrown innovation. Auto makers including General Motors have seen sales tumble and struggled to turn profitable as Chinese car shoppers increasingly opt for electric vehicles from BYD or NIO that are similar in price to internal-combustion-engine cars from foreign auto makers.

“China’s electric-vehicle makers have by leaps and bounds surpassed the capabilities of foreign brands who have a tie to the profit pool of internal combustible engines that they don’t want to disrupt,” says Christine Phillpotts, a fund manager for Ariel Investments’ emerging markets strategies.

Chinese companies are often faster than global rivals to market with new products or tweaks. “The cycle can be half of what it is for a global multinational with subsidiaries that need to check with headquarters, do an analysis, and then refresh,” Phillpotts says.

For many companies and investors, next year remains a question mark. Ashland CEO Guillermo Novo said in an August call with analysts that the chemical company was seeing a “big change” in China, with activity slowing and competition on pricing becoming more aggressive. The company, he said, was still trying to grasp the repercussions as it has created uncertainty in its 2025 outlook.

Few companies are giving up. Executives at big global consumer and retail companies show no signs of reducing investment, with most still describing China as a long-term growth market, says Dana Telsey, CEO of Telsey Advisory Group.

Starbucks executives described the long-term opportunity as “significant,” with higher growth and margin opportunities in the future as China’s population continues to move from rural to suburban areas. But they also noted that their approach is evolving and they are in the early stages of exploring strategic partnerships.

Walmart sold its stake in August in Chinese e-commerce giant JD.com for $3.6 billion after an eight-year noncompete agreement expired. Analysts expect it to pump the money into its own Sam’s Club and Walmart China operation, which have benefited from the trend toward trading down in China.

“The story isn’t over for the global companies,” Phillpotts says. “It just means the effort and investment will be greater to compete.”

Corrections & Amplifications

Joseph Quinlan is head of market strategy for the chief investment office at Merrill and Bank of America Private Bank. An earlier version of this article incorrectly used his old title.