Business Is Facing Up to the Risks of Destroying the Natural World

Companies from around the globe have volunteered to report their impact on nature

Companies from around the globe have volunteered to report their impact on nature

Hundreds of businesses have volunteered to measure and report their impact on the natural world, as they recognise the growing risks to their own operations from environmental degradation, including a denuded Amazon rainforest and dying coral reefs.

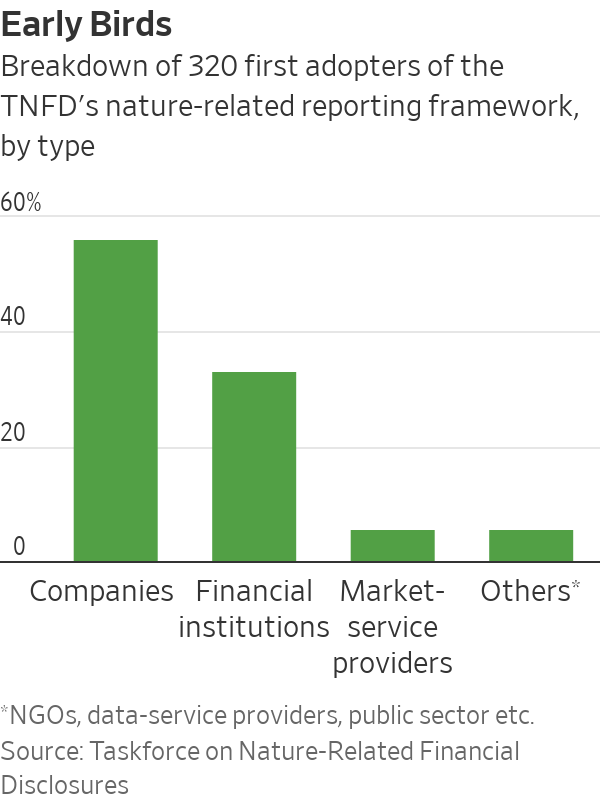

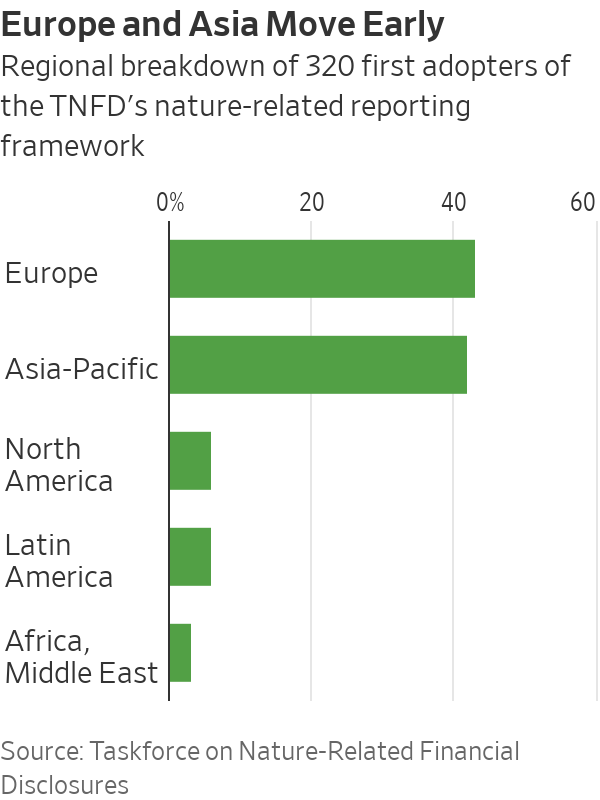

While many businesses are struggling to meet coming requirements to report their climate impact, more than 300 banks and companies are pledging to go much further. Early movers from across sectors and countries have promised to regularly publish nature-impact information as set out by the Taskforce on Nature-Related Financial Disclosures, or TNFD, a United Nations-backed initiative.

The first adopters represent $4 trillion in market capitalisation and around $14 trillion in assets under management. They include seven of the world’s 29 globally systemic banks, Japanese investor SoftBank, Norway’s sovereign-wealth fund, Gucci parent Kering, miner Anglo American and pharmaceutical majors GSK, AstraZeneca and Novo Nordisk.

Take-up by sector leaders should encourage peers to accelerate their efforts, said Tony Goldner, executive director of the TNFD. The framework is aligned to the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework agreed to in 2022 by nearly 200 countries. It recommends disclosures in governance, strategy, risk and impact management, as well as sector-specific metrics and targets for reducing impact.

Biodiversity impact is both a new type of risk and a new opportunity, said Valentin Alfaya, sustainability director at Spanish-listed infrastructure group Ferrovial, one of the first movers. “As a consequence of the implementation of the TNFD and our own natural capital assessment program, sometimes investments are going to be left aside,” Alfaya said.

“When you are interacting with those protected areas that are very relevant in terms of ecological value…it’s really risky for the company, not just in terms of reputation but also in terms of operations and even finance,” he said.

Using the framework will guide investment and help integrate nature into financial decision making, said Marisa Drew, chief sustainability officer at lender Standard Chartered. The move is a “significant opportunity for us to facilitate financial flows toward nature-positive outcomes,” Drew said.

Gauging impact is central to business decisions and managing risk, said Jennifer Motles, chief sustainability officer at tobacco giant Philip Morris International. “The TNFD recommendations and guidance will support us as we continue to focus on nature-related dependencies, impacts, risks, and opportunities,” Motles said.

The ramp-up in disclosure comes amid heightened awareness of the threat posed to the world by such natural degradation. The top four medium-term risks are all environmental, according to the World Economic Forum’s global risk report published earlier this month. They include extreme weather events, critical changes to the Earth’s systems, a collapse of the ecosystem and natural-resource shortages. “The collective ability to adapt to these impacts may be overwhelmed,” the report warns.

The World Bank estimates that the global economy could lose $2.7 trillion by 2030—which would mean a 10% drop, on average, in the economic output produced across all nations—if certain at-risk ecosystems collapse, such as fisheries or pollination by bees.

Adoption of the TNFD is “a clear signal that investors, lenders, insurers and companies are recognising that their business models and portfolios are highly dependent on both nature and climate,” the taskforce’s co-chair, David Craig, said. Natural risk should be treated both as a strategic risk and an investment opportunity, Craig said.

But reporting the damage done to the natural world isn’t the same as stopping it, said John Tobin-de la Puente, a professor of corporate sustainability at Cornell University. Disclosure is less about encouraging companies to change than it is about giving investors clear information on risk, he said.

Unlike carbon emissions, which can be assessed in terms of metric tons, there isn’t consensus on how to gauge environmental impact—whether, for example, in terms of protected species, general biodiversity, or a bundle of measures, said Tobin, a tropical ecologist and corporate lawyer by training. Some efforts have been made to create units of ecosystem impact, but for now, no universal metric exists, he said.

Alternatives to current business models will also need to be created, just as renewable energy has been developed to replace fossil fuels, Tobin said. “Will we get there at some point soon, before it’s too late for the biosphere?” he asked. “That question is still open.”

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

What a quarter-million dollars gets you in the western capital.

Alexandre de Betak and his wife are focusing on their most personal project yet.

CIOs can take steps now to reduce risks associated with today’s IT landscape

As tech leaders race to bring Windows systems back online after Friday’s software update by cybersecurity company CrowdStrike crashed around 8.5 million machines worldwide, experts share with CIO Journal their takeaways for preparing for the next major information technology outage.

IT leaders should hold vendors deeply integrated within IT systems, such as CrowdStrike , to a “very high standard” of development, release quality and assurance, said Neil MacDonald , a Gartner vice president.

“Any security vendor has a responsibility to do extensive regression testing on all versions of Windows before an update is rolled out,” he said.

That involves asking existing vendors to explain how they write software, what testing they do and whether customers may choose how quickly to roll out an update.

“Incidents like this remind all of us in the CIO community of the importance of ensuring availability, reliability and security by prioritizing guardrails such as deployment and testing procedures and practices,” said Amy Farrow, chief information officer of IT automation and security company Infoblox.

While automatically accepting software updates has become the norm—and a recommended security practice—the CrowdStrike outage is a reminder to take a pause, some CIOs said.

“We still should be doing the full testing of packages and upgrades and new features,” said Paul Davis, a field chief information security officer at software development platform maker JFrog . undefined undefined Though it’s not feasible to test every update, especially for as many as hundreds of software vendors, Davis said he makes it a priority to test software patches according to their potential severity and size.

Automation, and maybe even artificial intelligence-based IT tools, can help.

“Humans are not very good at catching errors in thousands of lines of code,” said Jack Hidary, chief executive of AI and quantum company SandboxAQ. “We need AI trained to look for the interdependence of new software updates with the existing stack of software.”

An incident rendering Windows computers unusable is similar to a natural disaster with systems knocked offline, said Gartner’s MacDonald. That’s why businesses should consider natural disaster recovery plans for maintaining the resiliency of their operations.

One way to do that is to set up a “clean room,” or an environment isolated from other systems, to use to bring critical systems back online, according to Chirag Mehta, a cybersecurity analyst at Constellation Research.

Businesses should also hold tabletop exercises to simulate risk scenarios, including IT outages and potential cyber threats, Mehta said.

Companies that back up data regularly were likely less impacted by the CrowdStrike outage, according to Victor Zyamzin, chief business officer of security company Qrator Labs. “Another suggestion for companies, and we’ve been saying that again and again for decades, is that you should have some backup procedure applied, running and regularly tested,” he said.

For any vendor with a significant impact on company operations , MacDonald said companies can review their contracts and look for clauses indicating the vendors must provide reliable and stable software.

“That’s where you may have an advantage to say, if an update causes an outage, is there a clause in the contract that would cover that?” he said.

If it doesn’t, tech leaders can aim to negotiate a discount serving as a form of compensation at renewal time, MacDonald added.

The outage also highlights the importance of insurance in providing companies with bottom-line protection against cyber risks, said Peter Halprin, a partner with law firm Haynes Boone focused on cyber insurance.

This coverage can include protection against business income losses, such as those associated with an outage, whether caused by the insured company or a service provider, Halprin said.

The CrowdStrike update affected only devices running Microsoft Windows-based systems , prompting fresh questions over whether enterprises should rely on Windows computers.

CrowdStrike runs on Windows devices through access to the kernel, the part of an operating system containing a computer’s core functions. That’s not the same for Apple ’s Mac operating system and Linux, which don’t allow the same level of access, said Mehta.

Some businesses have converted to Chromebooks , simple laptops developed by Alphabet -owned Google that run on the Chrome operating system . “Not all of them require deeper access to things,” Mehta said. “What are you doing on your laptop that actually requires Windows?”