China Exports Fall for a Fourth Month as Once-Reliable Growth Engine Sputters

Property sector’s downturn has pushed imports to their 11th month of declines in the past year

Property sector’s downturn has pushed imports to their 11th month of declines in the past year

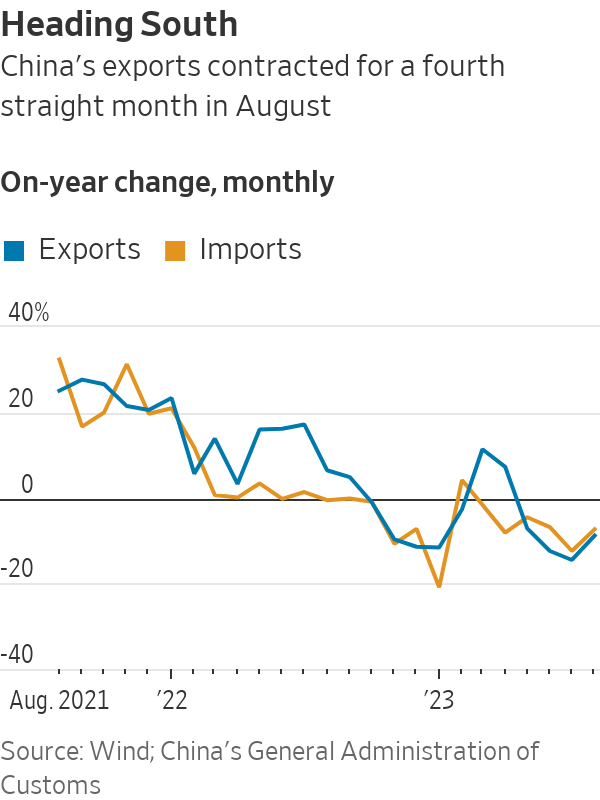

HONG KONG—China’s exports to the rest of the world dropped for a fourth straight month in August, bringing little relief to the country from a deepening economic malaise and weighing on the global trade outlook.

China has struggled to sustain a wave of overseas demand for Chinese-made goods that carried it through much of the three years of the pandemic, particularly as Western consumers tilted their spending back toward services and away from smartphones, furniture and other goods. Higher borrowing rates in the U.S. and other developed countries also hit consumer appetite.

Meanwhile, Chinese imports continued to shrink in August, a reflection of lacklustre consumer demand even after the country loosened its longstanding Covid-related restrictions. A downturn in China’s property market has also sapped demand for raw materials used in construction.

Taken together, the sluggish trade data released Thursday by Beijing provides new evidence that the world’s second-largest economy is struggling to revive domestic demand.

That would ripple through the global economy as China’s slowdown weighs on oil prices and hurts commodity-exporting countries such as Australia, Brazil and Canada. Chinese manufacturers have been under pressure to cut prices to retain market share, potentially sending disinflationary currents around the world.

While Chinese policy makers have trimmed key interest rates and made new attempts to revive home-buying sentiment, economists have widely dismissed these efforts as too piecemeal to revive growth given the speed with which sentiment has soured.

“There’s still a steep hill to climb to get the all-clear on stabilisation for China,” said Frederic Neumann, chief Asia economist at HSBC.

China’s outbound shipments declined 8.8% in August from a year earlier, China’s General Administration of Customs said Thursday. The reading narrowed from the 14.5% year-over-year drop in exports in July, which marked the worst such result since February 2020.

Imports to China, including intermediate components, commodities and consumer products, fell 7.3% in August from a year earlier, slower than July’s 12.4% drop.

Even with the better-than-feared trade data, economists generally agree that exports’ ability to provide support for China’s sputtering recovery remains a distant prospect, particularly given that global trade is expected to contract this year.

“We expect exports to decline over the coming months before bottoming out toward the end of the year,” research firm Capital Economics told clients in a note Thursday.

Apart from the general slowdown in trade, China is facing a raft of other economic headwinds. After a brief spurt of spending in traveling and dining out upon reopening early this year, consumers tightened their purse strings, dragging consumer prices into deflationary territory in July. China is set to report August inflation data on Saturday.

Factory activity, meantime, reported a fifth straight month of contraction in August, while a years long downturn in the housing market has only deepened in recent months. Private investment remains depressed, while the youth jobless rate climbed to a series of record highs in the summer before Beijing decided to discontinue releasing the data to the public.

More broadly, the run of downbeat data during the summer months has sparked growing concerns over China’s long-term growth trajectory and prompted several investment banks to trim their growth forecasts for gross domestic product to below 5% for the year, compared with the official government target of around 5%, which was set in March.

Meeting with Southeast Asian leaders this week, Chinese Premier Li Qiang struck back against widespread pessimism about the country’s near-term economic outlook, saying the country is on track to hit its growth target for the year.

While Chinese policy makers have rolled out a batch of stimulus measures in recent weeks, including trimming interest rates for businesses and home buyers and extending tax relief to households, many economists have questioned whether the policies will be enough to turn around weak consumer sentiment.

China’s reduced appetite for imports—which have fallen for 11 of the past 12 months—reflects in large part the knock-on effects of the country’s continuing property crisis. Both property investment and new construction starts have plunged in recent months amid a loss of confidence in home prices; that in turn has curbed China’s appetite for commodities such as iron ore.

The export data, meanwhile, offers more evidence of China’s shifting trade patterns.

As ties have soured between Beijing and Washington, many U.S. companies have begun to redirect supply chains away from China and toward other Asian countries such as India, leading to a sharp decline in America’s reliance on goods from China.

Rising operational uncertainty, made most clear during China’s pandemic-era lockdowns, which disrupted domestic and global production and logistics, heightened the urgency for many multinationals.

In the first half of the year, China accounted for 13.3% of U.S. goods imports, down from a high of 21.6% in 2017 and representing the lowest level since 2003.

Meanwhile, trade with the 10-member Association of Southeast Asian Nations has grown over the past year to become China’s largest export market, ahead of the U.S. and European Union, according to a recent report by HSBC.

China’s warmer trade relations with Asian countries will help buffer the impact of softening Chinese exports to advanced economies. But economists say Beijing won’t be immune if the U.S. and other advanced economies tip into recession.

Global goods trade is expected to drop by 1.5% this year in part due to tightening global monetary and credit conditions before staging a modest recovery of 2.3% growth in 2024, according to estimates by Adam Slater, lead economist at Oxford Economics.

China’s weakening trade activities, meanwhile, is likely to ripple across Asia, slowing industrial expansion and hitting commodity prices, he added.

—Xiao Xiao in Beijing contributed to this article.

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

What a quarter-million dollars gets you in the western capital.

Alexandre de Betak and his wife are focusing on their most personal project yet.

CIOs can take steps now to reduce risks associated with today’s IT landscape

As tech leaders race to bring Windows systems back online after Friday’s software update by cybersecurity company CrowdStrike crashed around 8.5 million machines worldwide, experts share with CIO Journal their takeaways for preparing for the next major information technology outage.

IT leaders should hold vendors deeply integrated within IT systems, such as CrowdStrike , to a “very high standard” of development, release quality and assurance, said Neil MacDonald , a Gartner vice president.

“Any security vendor has a responsibility to do extensive regression testing on all versions of Windows before an update is rolled out,” he said.

That involves asking existing vendors to explain how they write software, what testing they do and whether customers may choose how quickly to roll out an update.

“Incidents like this remind all of us in the CIO community of the importance of ensuring availability, reliability and security by prioritizing guardrails such as deployment and testing procedures and practices,” said Amy Farrow, chief information officer of IT automation and security company Infoblox.

While automatically accepting software updates has become the norm—and a recommended security practice—the CrowdStrike outage is a reminder to take a pause, some CIOs said.

“We still should be doing the full testing of packages and upgrades and new features,” said Paul Davis, a field chief information security officer at software development platform maker JFrog . undefined undefined Though it’s not feasible to test every update, especially for as many as hundreds of software vendors, Davis said he makes it a priority to test software patches according to their potential severity and size.

Automation, and maybe even artificial intelligence-based IT tools, can help.

“Humans are not very good at catching errors in thousands of lines of code,” said Jack Hidary, chief executive of AI and quantum company SandboxAQ. “We need AI trained to look for the interdependence of new software updates with the existing stack of software.”

An incident rendering Windows computers unusable is similar to a natural disaster with systems knocked offline, said Gartner’s MacDonald. That’s why businesses should consider natural disaster recovery plans for maintaining the resiliency of their operations.

One way to do that is to set up a “clean room,” or an environment isolated from other systems, to use to bring critical systems back online, according to Chirag Mehta, a cybersecurity analyst at Constellation Research.

Businesses should also hold tabletop exercises to simulate risk scenarios, including IT outages and potential cyber threats, Mehta said.

Companies that back up data regularly were likely less impacted by the CrowdStrike outage, according to Victor Zyamzin, chief business officer of security company Qrator Labs. “Another suggestion for companies, and we’ve been saying that again and again for decades, is that you should have some backup procedure applied, running and regularly tested,” he said.

For any vendor with a significant impact on company operations , MacDonald said companies can review their contracts and look for clauses indicating the vendors must provide reliable and stable software.

“That’s where you may have an advantage to say, if an update causes an outage, is there a clause in the contract that would cover that?” he said.

If it doesn’t, tech leaders can aim to negotiate a discount serving as a form of compensation at renewal time, MacDonald added.

The outage also highlights the importance of insurance in providing companies with bottom-line protection against cyber risks, said Peter Halprin, a partner with law firm Haynes Boone focused on cyber insurance.

This coverage can include protection against business income losses, such as those associated with an outage, whether caused by the insured company or a service provider, Halprin said.

The CrowdStrike update affected only devices running Microsoft Windows-based systems , prompting fresh questions over whether enterprises should rely on Windows computers.

CrowdStrike runs on Windows devices through access to the kernel, the part of an operating system containing a computer’s core functions. That’s not the same for Apple ’s Mac operating system and Linux, which don’t allow the same level of access, said Mehta.

Some businesses have converted to Chromebooks , simple laptops developed by Alphabet -owned Google that run on the Chrome operating system . “Not all of them require deeper access to things,” Mehta said. “What are you doing on your laptop that actually requires Windows?”