Don’t Roll Your Eyes: Looking the Part Could Land You That Job

Applying to be a programmer? Better grab a pair of glasses. Different jobs favour certain looks, new research shows.

Applying to be a programmer? Better grab a pair of glasses. Different jobs favour certain looks, new research shows.

Think appearances don’t matter if you’re applying for a job online? New research shows that looking the part is very much part of the equation.

Your credentials and referrals may get you on the shortlist. Even if the whole process takes place online, though, it’s rare that a hiring manager won’t check out your LinkedIn profile. Making the final cut can come down to nailing a specific professional look, according to a new study published by the Harvard Business School.

Analysing 63,000 job openings and the more than 160,000 freelancers who applied for them over a six-month period, researchers found that certain accessories or physical features gave candidates an edge in landing the job—even after controlling for race, age and gender. Researchers used computer vision technology and machine learning to help classify which attributes made someone be perceived as a better fit for a job, then examined what role that played in hiring.

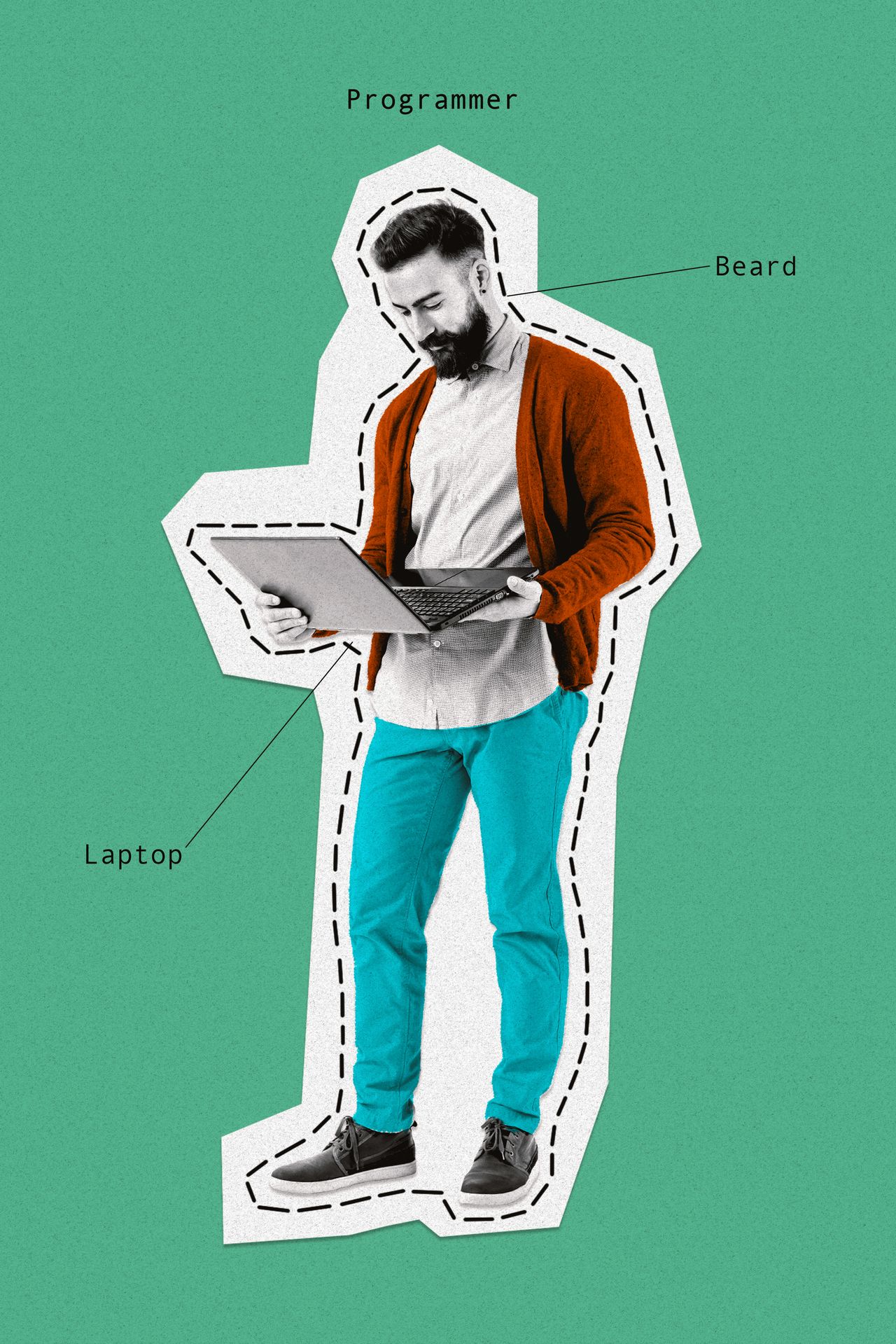

Different jobs favoured certain looks. The analysis showed that men wearing glasses and having a computer visible in the photo were perceived to be a better fit for a software programming assignment than men without glasses, boosting their chances of getting it. A beard gave them a slight edge, too.

With design and media-related jobs—one of two broad job categories examined in the study—flashing a smile and using a photo with high image quality was also important. Women sporting reading glasses and an “artistic” look were seen as a better fit for graphic design jobs than other women.

The researchers, from Harvard and the University of Southern California, found that certain photo features could tilt the selection process when profiles included equally high ratings from previous clients. The advantage could be roughly the equivalent of a 5% pay differential.

On the other hand, the study suggests that looking the part for a job doesn’t rely just on a candidate’s gender, ethnicity and age. Rather, paying attention to the details of a profile photo can go a long way, recruiters say.

“We would be fooling ourselves to say it’s not part of the package,” says Jessica Vann, founder of Maven Recruiting Group, a San Francisco job-placement firm. While not as important as job or communication skills, “it’s a piece, for sure.”

It’s generally a good idea to have a neutral background and no children, pets or celebrities in the photo. Vann, whose firm specialises in placing executive assistants and chiefs of staff at Silicon Valley companies, says she has counselled job seekers to eschew an obviously AI-generated photo or tone down the makeup.

In a CivicScience poll of more than 2,000 people conducted online last week, about half of respondents said they had used a professional-looking photo of themselves in some capacity; 82% agree that appearance makes a difference in a job offer.

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibits employers from discriminating because of race, gender and religion, among other factors. But other aspects of personal appearance—whether height, weight or hairstyle—aren’t necessarily covered by the federal statute, says Steven Pearlman, a labor attorney at Proskauer Rose in Chicago. Plus, it’s often difficult to legally prove whether such biases were the reason for a candidate’s rejection.

Brent McCreary, a theatre ticketing director in New York, has found certain photo details can swing a hiring manager’s decision either way. His professional profile picture usually shows him with a favorite celebrity. At one point it was Britney Spears. Now it’s Kelly Clarkson.

The choice worked against him when he lost out on a revenue management job at a theme park three years ago. In the rejection note, the interviewer suggested a more professional LinkedIn photo.

A month later, though, the executive director of a San Francisco-based streaming platform contacted him. The job he’d applied for was already filled but she noticed his photo. “Your personality and background seem so fun and special,” she wrote in a LinkedIn message. When another project-management job opened soon after, McCreary got it. The job turned out to be a better fit for him, too, he says.

“The company I ended up working for was one where I kind of jelled with the organisation,” he says.

Looking the part is often informed by stories and stereotypes, career coaches say. “You see it in books and movies,” says Catherine Fisher, a LinkedIn career expert who studies data and trends on the professional social media network.

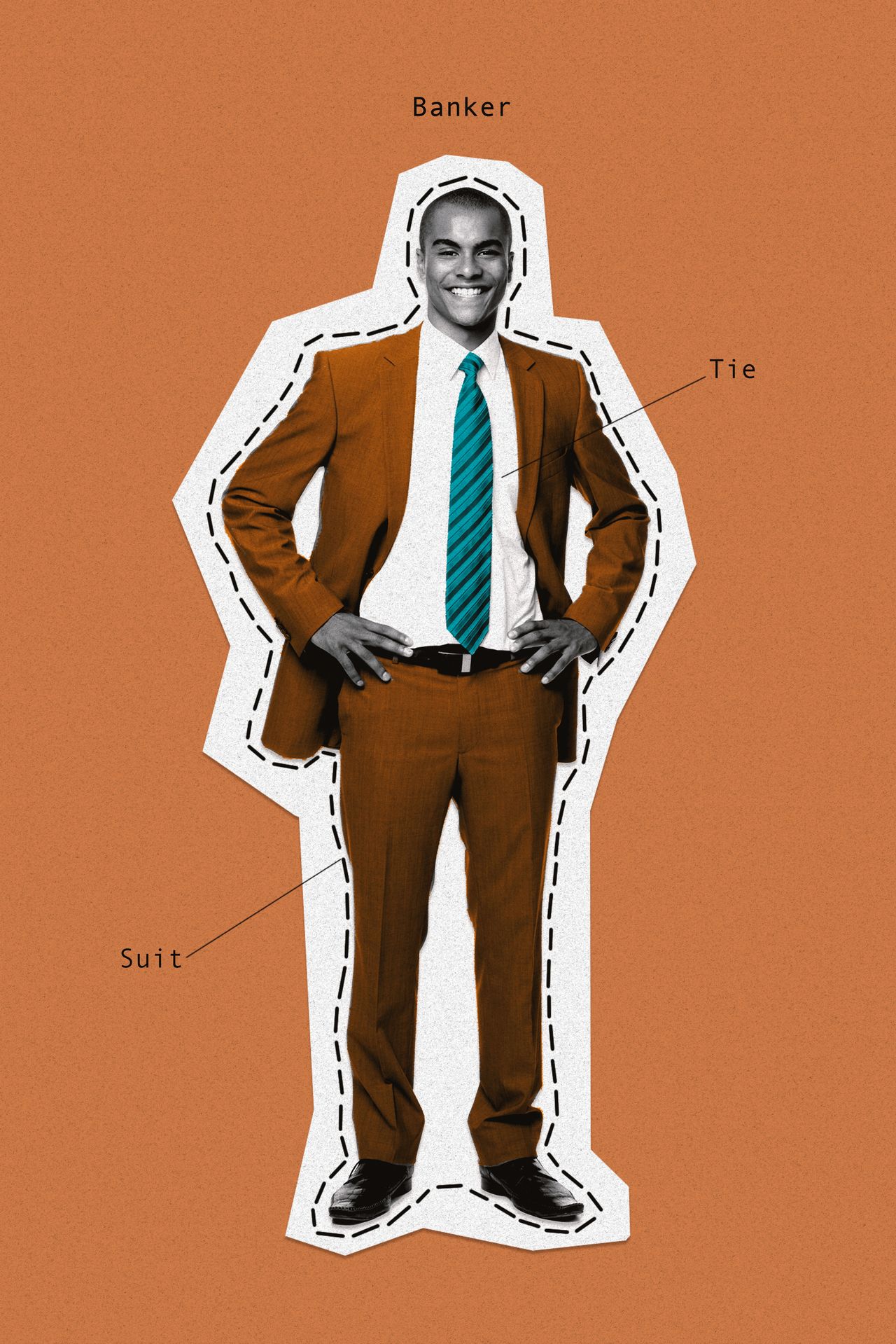

Every industry has its own sartorial vibe, from the fleeced vests and sweatshirts of Silicon Valley to the traditionally suited-up finance crowd in New York.

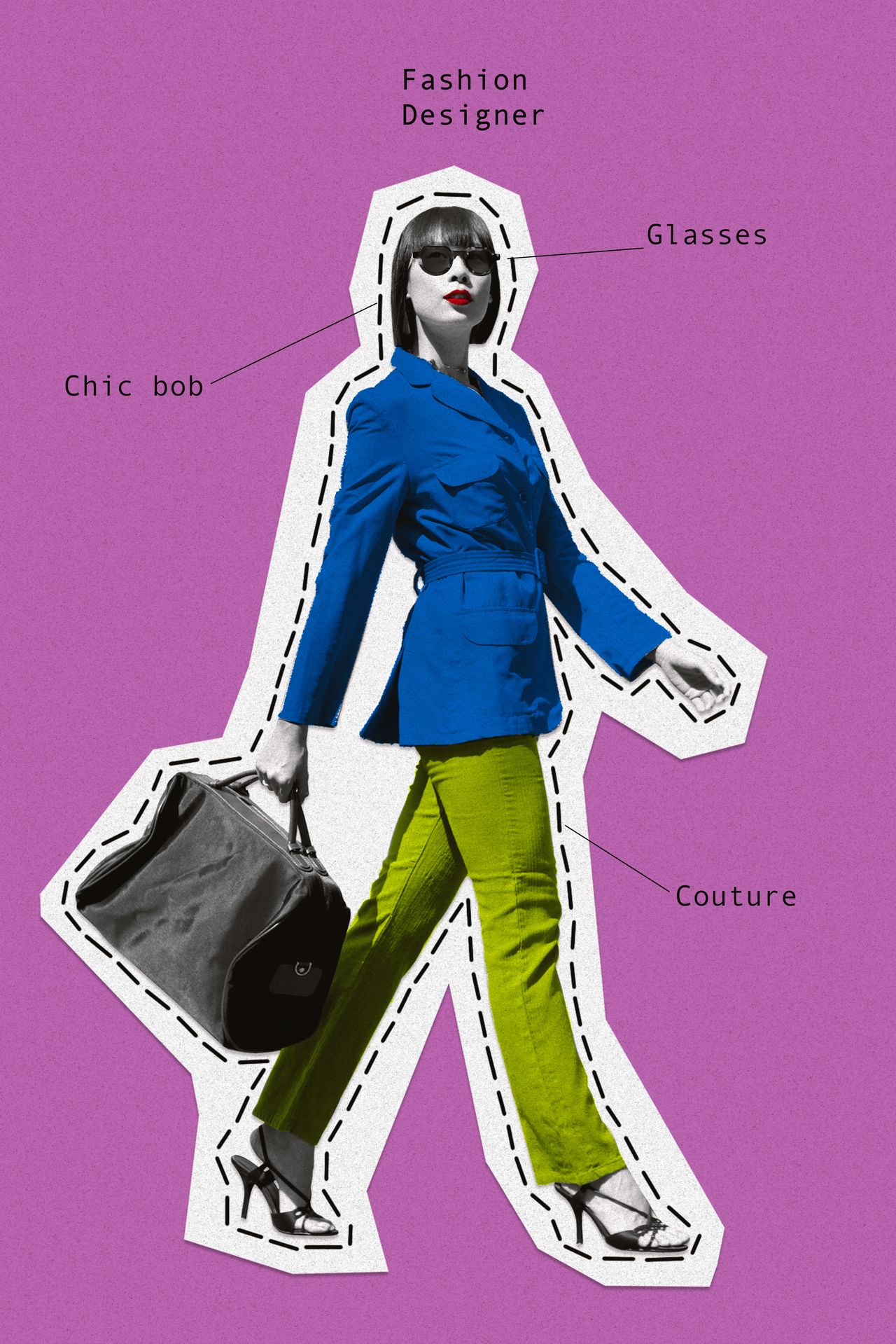

“You always think hoodies are related to tech companies, but that doesn’t mean I have to wear one,” Fisher says. By the same token, angular bobs and big sunglasses have come to be associated with the fashion industry, though “not everyone in fashion looks like Anna Wintour,” she says.

That’s rapidly changing as home and work life become more mixed, Fisher says. More than half of working Americans say that how they present themselves at work has changed since the pandemic, according to a poll of 2,000 people conducted last year by LinkedIn. Two-thirds said they thought that managers and co-workers were more accepting of different ways of dressing and styling than several years ago.

Alice Stephenson, a 42-year-old lawyer, says that for much of her early career, she dressed the part and concealed her piercings and tattoos. “I wore a stereotype of what a professional looked like,” she says. “I never felt comfortable or able to express my own individuality or creativity through my appearance.”

That changed after she started her own law firm. In her photo on the firm’s website, in her email signature and on LinkedIn, she is wearing a friendly smile, a blue sleeveless dress and a visible sleeve of tattoos.

“I want to look friendly and approachable,” says Stephenson, who lives in Amsterdam. “That’s key to my brand.”

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

What a quarter-million dollars gets you in the western capital.

Alexandre de Betak and his wife are focusing on their most personal project yet.

CIOs can take steps now to reduce risks associated with today’s IT landscape

As tech leaders race to bring Windows systems back online after Friday’s software update by cybersecurity company CrowdStrike crashed around 8.5 million machines worldwide, experts share with CIO Journal their takeaways for preparing for the next major information technology outage.

IT leaders should hold vendors deeply integrated within IT systems, such as CrowdStrike , to a “very high standard” of development, release quality and assurance, said Neil MacDonald , a Gartner vice president.

“Any security vendor has a responsibility to do extensive regression testing on all versions of Windows before an update is rolled out,” he said.

That involves asking existing vendors to explain how they write software, what testing they do and whether customers may choose how quickly to roll out an update.

“Incidents like this remind all of us in the CIO community of the importance of ensuring availability, reliability and security by prioritizing guardrails such as deployment and testing procedures and practices,” said Amy Farrow, chief information officer of IT automation and security company Infoblox.

While automatically accepting software updates has become the norm—and a recommended security practice—the CrowdStrike outage is a reminder to take a pause, some CIOs said.

“We still should be doing the full testing of packages and upgrades and new features,” said Paul Davis, a field chief information security officer at software development platform maker JFrog . undefined undefined Though it’s not feasible to test every update, especially for as many as hundreds of software vendors, Davis said he makes it a priority to test software patches according to their potential severity and size.

Automation, and maybe even artificial intelligence-based IT tools, can help.

“Humans are not very good at catching errors in thousands of lines of code,” said Jack Hidary, chief executive of AI and quantum company SandboxAQ. “We need AI trained to look for the interdependence of new software updates with the existing stack of software.”

An incident rendering Windows computers unusable is similar to a natural disaster with systems knocked offline, said Gartner’s MacDonald. That’s why businesses should consider natural disaster recovery plans for maintaining the resiliency of their operations.

One way to do that is to set up a “clean room,” or an environment isolated from other systems, to use to bring critical systems back online, according to Chirag Mehta, a cybersecurity analyst at Constellation Research.

Businesses should also hold tabletop exercises to simulate risk scenarios, including IT outages and potential cyber threats, Mehta said.

Companies that back up data regularly were likely less impacted by the CrowdStrike outage, according to Victor Zyamzin, chief business officer of security company Qrator Labs. “Another suggestion for companies, and we’ve been saying that again and again for decades, is that you should have some backup procedure applied, running and regularly tested,” he said.

For any vendor with a significant impact on company operations , MacDonald said companies can review their contracts and look for clauses indicating the vendors must provide reliable and stable software.

“That’s where you may have an advantage to say, if an update causes an outage, is there a clause in the contract that would cover that?” he said.

If it doesn’t, tech leaders can aim to negotiate a discount serving as a form of compensation at renewal time, MacDonald added.

The outage also highlights the importance of insurance in providing companies with bottom-line protection against cyber risks, said Peter Halprin, a partner with law firm Haynes Boone focused on cyber insurance.

This coverage can include protection against business income losses, such as those associated with an outage, whether caused by the insured company or a service provider, Halprin said.

The CrowdStrike update affected only devices running Microsoft Windows-based systems , prompting fresh questions over whether enterprises should rely on Windows computers.

CrowdStrike runs on Windows devices through access to the kernel, the part of an operating system containing a computer’s core functions. That’s not the same for Apple ’s Mac operating system and Linux, which don’t allow the same level of access, said Mehta.

Some businesses have converted to Chromebooks , simple laptops developed by Alphabet -owned Google that run on the Chrome operating system . “Not all of them require deeper access to things,” Mehta said. “What are you doing on your laptop that actually requires Windows?”