He Stole Hundreds of iPhones and Looted People’s Life Savings. He Told Us How.

A convicted iPhone thief explains how a vulnerability in Apple’s software got him fast cash—and then a stint in a high-security prison

A convicted iPhone thief explains how a vulnerability in Apple’s software got him fast cash—and then a stint in a high-security prison

RUSH CITY, Minn.—Before the guards let you through the barbed-wire fences and steel doors at this Minnesota Correctional Facility, you have to leave your phone in a locker. Not a total inconvenience when you’re there to visit a prolific iPhone thief.

I wasn’t worried that Aaron Johnson would steal my iPhone, though. I came to find out how he’d steal it.

“I’m already serving time. I just feel like I should try to be on the other end of things and try to help people,” Johnson, 26 years old, told me in an interview we filmed inside the high-security prison where he’s expected to spend the next several years.

For the past year, my colleague Nicole Nguyen and I have investigated a nationwide spate of thefts, where thieves watch iPhone owners tap their passcodes, then steal their targets’ phones—and upend their financial and digital lives.

Johnson, along with a crew of others, operated in Minneapolis for at least a year during 2021 and 2022. In and around bars at night, he would befriend young people, slyly learn their passcodes and take their phones. Using that code, he’d lock victims out of their Apple accounts and loot thousands of dollars from their bank apps. Finally, he’d sell the phones themselves.

It was an elaborate, opportunistic scheme that exploited the Apple ecosystem and targeted trusting iPhone owners who figured a stolen phone was just a stolen phone.

Last week, Apple announced Stolen Device Protection, a feature that likely will protect against these passcode-assisted crimes.

Yet even when you install the software, due in iOS 17.3, there will be loopholes. The biggest loophole? Us. By hearing how Johnson did what he did, we can learn how to better secure the devices that hold so much of our lives.

Johnson isn’t a sophisticated cybercriminal. He said he got his start pickpocketing on the streets of Minneapolis. “I was homeless,” he said. “Started having kids and needed money. I couldn’t really find a job. So that’s just what I did.”

Soon he realised the phones he was nabbing could be worth a lot more—if only he had a way to get inside them. Johnson said no one taught him the passcode trick, he just stayed up late one night fiddling with a phone and figured out how to use the passcode to unlock a bounty of protected services.

“That passcode is the devil,” he said. “It could be God sometimes—or it could be the devil.”

According to the Minneapolis Police Department’s arrest warrant, Johnson and the other 11 members of the enterprise allegedly accumulated nearly $300,000. According to him, it was likely more.

“I had a rush for large amounts at a time,” he said. “I just got too carried away.”

In March, Johnson, who had prior robbery and theft convictions, pleaded guilty to racketeering and was sentenced to 94 months. He told the judge he was sorry for what he did.

Here’s how the nightly operation would go down, according to interviews with Johnson, law-enforcement officials and some of the victims:

Pinpoint the victim. Dimly lit and full of people, bars became his ideal location. College-age men became his ideal target. “They’re already drunk and don’t know what’s going on for real,” Johnson said. Women, he said, tended to be more guarded and alert to suspicious behaviour.

Get the passcode. Friendly and energetic, that’s how victims described Johnson. Some told me he approached them offering drugs. Others said Johnson would tell them he was a rapper and wanted to add them on Snapchat. After talking for a bit, they would hand over the phone to Johnson, thinking he’d just input his info and hand it right back.

“I say, ‘Hey, your phone is locked. What’s the passcode?’ They say, ‘2-3-4-5-6,’ or something. And then I just remember it,” Johnson described. Sometimes he would record people typing their passcodes.

Once the phone was in his hand, he’d leave with it or pass it to someone else in the crew.

Lock them out—fast. Within minutes of taking the iPhones, Johnson was in the Settings menu, changing the Apple ID password. He’d then use the new password to turn off Find My iPhone so victims couldn’t log in on some other phone or computer to remotely locate—and even erase—the stolen device.

Johnson was changing passwords fast—“faster than you could say supercalifragilisticexpialidocious,” he said. “You gotta beat the mice to the cheese.”

Take the money. Johnson said he would then enrol his face in Face ID because “when you got your face on there, you got the key to everything.” The biometric authentication gave Johnson quick access to passwords saved in iCloud Keychain.

Savings, checking, cryptocurrency apps—he was looking to transfer large sums of money out. And if he had trouble getting into those money apps, he’d look for extra information, such as Social Security numbers, in the Notes and Photos apps.

By the morning, he’d have the money transferred. That’s when he’d head to stores to buy stuff using Apple Pay. He’d also use the stolen Apple devices to buy more Apple devices, most often $1,200 iPad Pro models, to sell for cash.

Sell the phones. Finally, he’d erase the phone and sell it to Zhongshuang “Brandon” Su who, according to his arrest warrant, sold them overseas.

While Johnson did steal some Android phones, he went after iPhones because of their higher resale value. At bars, he’d scope out the scene—looking for iPhone Pro models with their telltale trio of cameras. He said Pro Max with a terabyte of storage could get him $900. Su also bought Johnson’s purchased iPads.

Su pleaded guilty to receiving stolen property and was sentenced to 120 days at an adult corrections facility in Hennepin County, Minn. Neither Su nor his lawyer responded to requests for comment.

On a good weekend, Johnson said, he was selling up to 30 iPhones and iPads to Su and making around $20,000—not including money he’d taken from victims’ bank apps, Apple Pay and more.

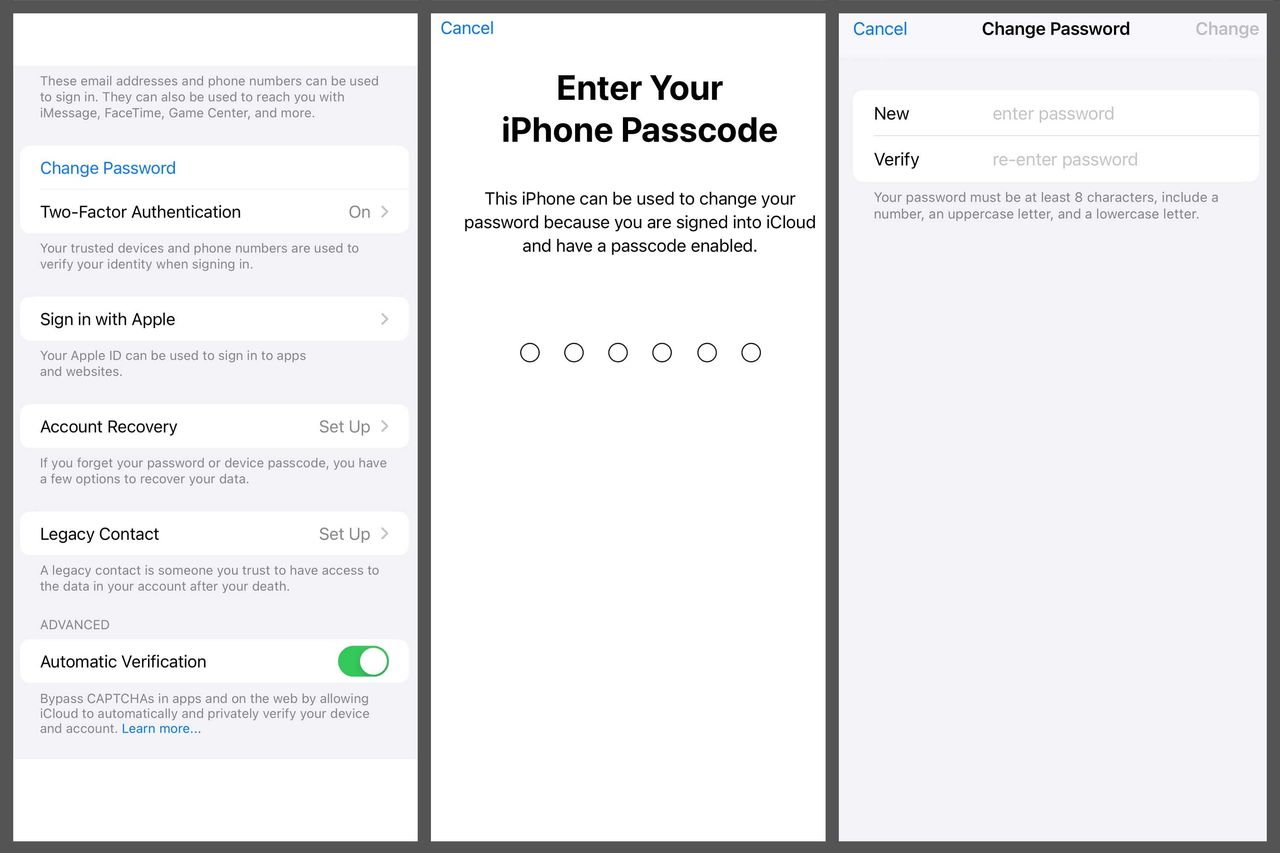

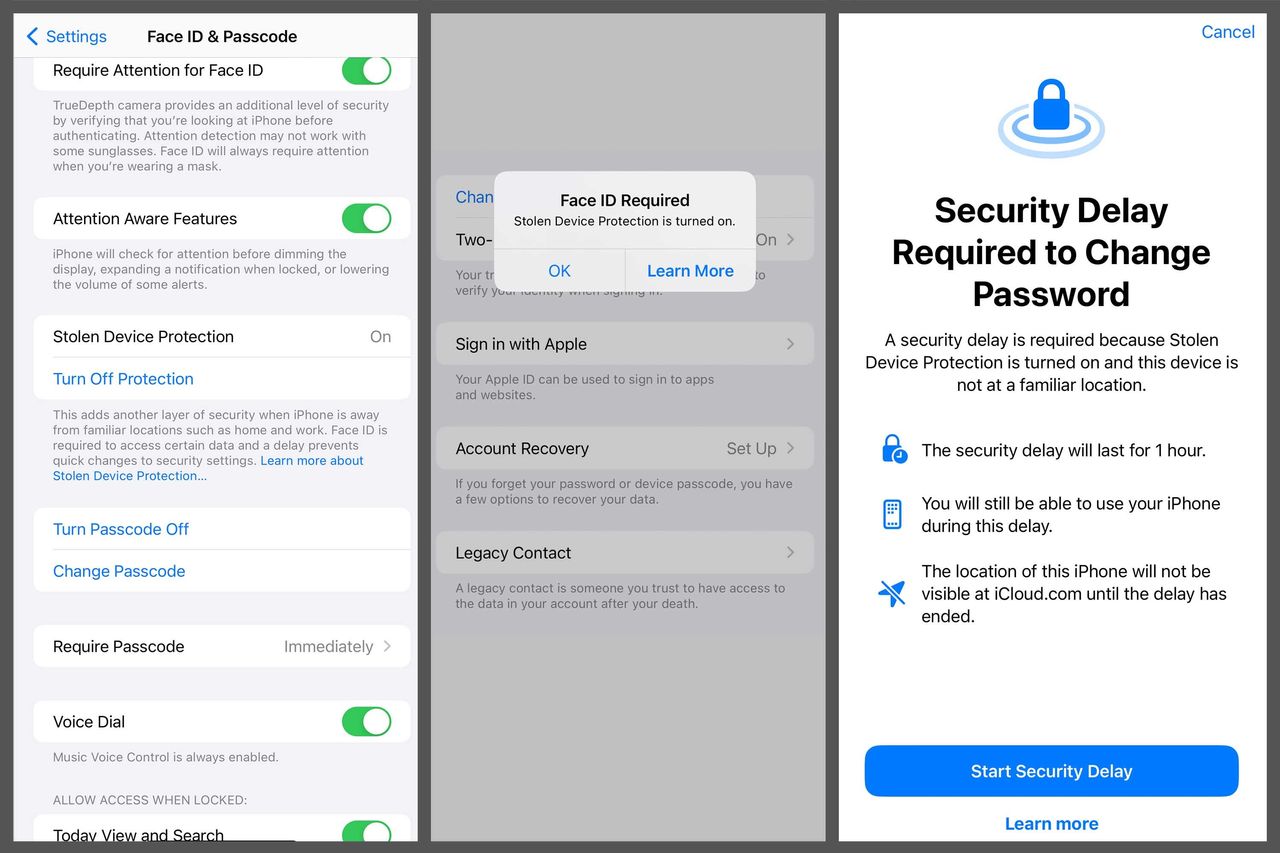

A week after my trip to Minnesota, Apple announced Stolen Device Protection. The security setting will likely foil most of Johnson’s tricks, but it won’t be turned on automatically.

If you don’t turn it on, you’re as vulnerable as ever. Switching it on adds a line of defence to your phone when away from familiar locations such as home or work.

To change the Apple ID password, a thief would need Face ID or Touch ID biometric scans—that is, your face or your finger. The passcode alone won’t work. And the process has a built-in hourlong delay, followed by another biometric scan. This same slow process is also required for adding a new Face ID and disabling Find my iPhone.

Some functions, such as accessing saved passwords in iCloud Keychain or erasing the iPhone, are available without the delay but still require Face ID or Touch ID.

A criminal might still be motivated to kidnap a person with lots of money, then slowly break through these layers of security. However, the protections will likely dissuade thieves who just want to grab phones and flee the scene.

So what loopholes remain? A thief who gets the passcode could still buy things with Apple Pay. And any app that isn’t protected by an additional password or PIN—like your email, Venmo, PayPal and more—is also vulnerable.

That’s why you should also:

The most obvious is Johnson’s advice: Watch your surroundings and don’t give your passcode out.

If this crime has taught us anything, it’s that a single device now contains access to our entire lives—our memories, our money and more. It’s on us to protect them.

—Nicole Nguyen contributed to this article.

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

What a quarter-million dollars gets you in the western capital.

Alexandre de Betak and his wife are focusing on their most personal project yet.

CIOs can take steps now to reduce risks associated with today’s IT landscape

As tech leaders race to bring Windows systems back online after Friday’s software update by cybersecurity company CrowdStrike crashed around 8.5 million machines worldwide, experts share with CIO Journal their takeaways for preparing for the next major information technology outage.

IT leaders should hold vendors deeply integrated within IT systems, such as CrowdStrike , to a “very high standard” of development, release quality and assurance, said Neil MacDonald , a Gartner vice president.

“Any security vendor has a responsibility to do extensive regression testing on all versions of Windows before an update is rolled out,” he said.

That involves asking existing vendors to explain how they write software, what testing they do and whether customers may choose how quickly to roll out an update.

“Incidents like this remind all of us in the CIO community of the importance of ensuring availability, reliability and security by prioritizing guardrails such as deployment and testing procedures and practices,” said Amy Farrow, chief information officer of IT automation and security company Infoblox.

While automatically accepting software updates has become the norm—and a recommended security practice—the CrowdStrike outage is a reminder to take a pause, some CIOs said.

“We still should be doing the full testing of packages and upgrades and new features,” said Paul Davis, a field chief information security officer at software development platform maker JFrog . undefined undefined Though it’s not feasible to test every update, especially for as many as hundreds of software vendors, Davis said he makes it a priority to test software patches according to their potential severity and size.

Automation, and maybe even artificial intelligence-based IT tools, can help.

“Humans are not very good at catching errors in thousands of lines of code,” said Jack Hidary, chief executive of AI and quantum company SandboxAQ. “We need AI trained to look for the interdependence of new software updates with the existing stack of software.”

An incident rendering Windows computers unusable is similar to a natural disaster with systems knocked offline, said Gartner’s MacDonald. That’s why businesses should consider natural disaster recovery plans for maintaining the resiliency of their operations.

One way to do that is to set up a “clean room,” or an environment isolated from other systems, to use to bring critical systems back online, according to Chirag Mehta, a cybersecurity analyst at Constellation Research.

Businesses should also hold tabletop exercises to simulate risk scenarios, including IT outages and potential cyber threats, Mehta said.

Companies that back up data regularly were likely less impacted by the CrowdStrike outage, according to Victor Zyamzin, chief business officer of security company Qrator Labs. “Another suggestion for companies, and we’ve been saying that again and again for decades, is that you should have some backup procedure applied, running and regularly tested,” he said.

For any vendor with a significant impact on company operations , MacDonald said companies can review their contracts and look for clauses indicating the vendors must provide reliable and stable software.

“That’s where you may have an advantage to say, if an update causes an outage, is there a clause in the contract that would cover that?” he said.

If it doesn’t, tech leaders can aim to negotiate a discount serving as a form of compensation at renewal time, MacDonald added.

The outage also highlights the importance of insurance in providing companies with bottom-line protection against cyber risks, said Peter Halprin, a partner with law firm Haynes Boone focused on cyber insurance.

This coverage can include protection against business income losses, such as those associated with an outage, whether caused by the insured company or a service provider, Halprin said.

The CrowdStrike update affected only devices running Microsoft Windows-based systems , prompting fresh questions over whether enterprises should rely on Windows computers.

CrowdStrike runs on Windows devices through access to the kernel, the part of an operating system containing a computer’s core functions. That’s not the same for Apple ’s Mac operating system and Linux, which don’t allow the same level of access, said Mehta.

Some businesses have converted to Chromebooks , simple laptops developed by Alphabet -owned Google that run on the Chrome operating system . “Not all of them require deeper access to things,” Mehta said. “What are you doing on your laptop that actually requires Windows?”