How an Ex-Teacher Turned a Tiny Pension Into a Giant-Killer

A bold bet on rising rates lifted a small Massachusetts fund near the top of the performance rankings

A bold bet on rising rates lifted a small Massachusetts fund near the top of the performance rankings

Plymouth County is known for Pilgrims, cranberries—and a top-performing pension fund run by a 65-year-old former schoolteacher.

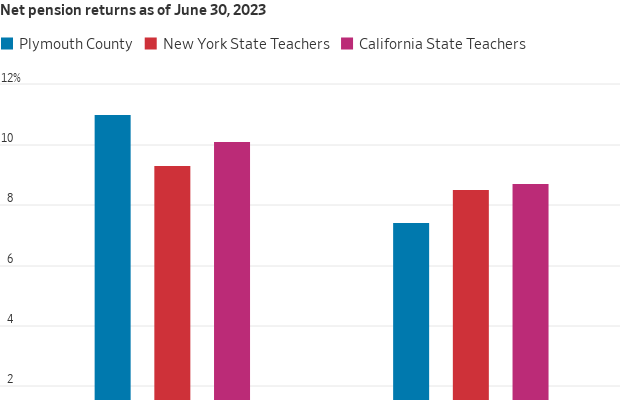

After a decade of mostly ho-hum performance, the $1.4 billion Plymouth County Retirement Association ranked in the top 10% of U.S. pensions over the past three years. Key to that success was an early—and prescient—bet that interest rates would rise. That buoyed the fund through big chunks of the past two years, when climbing rates hammered both stocks and bonds.

Now markets of all kinds have posted a six-month rally , stocks are hitting records and Plymouth risks falling behind again. But Peter Manning, the fund’s director of investments, is sticking to his guns. The hope that rates will fall soon is misplaced, he said. Another downturn could be coming for Wall Street.

And so, to Manning, the best way to enlarge the pension long term is by avoiding big losses, rather than chasing high returns.

“It ain’t about what you make. It’s about what you keep,” he said.

The fund, which manages savings for the county’s firefighters, bus drivers and custodians, delivered average annual net returns of 5.7% in the three years ending Dec. 31. That put it ahead of 92% of pensions nationally. The median U.S. public retirement fund returned 3.7% over the same period, according to Investment Metrics, a portfolio analysis provider.

Plymouth County surpassed bigger peers by slashing exposure to Treasurys and public stocks before they tanked in 2022. The fund then reinvested the money in infrastructure, private equity and inflation-protected debt.

While many other public plans have followed suit , the trades were also unusually quick for pension funds, which often change investments incrementally rather than in bold strokes.

“A lot of our clients made moves on the margin,” said Daniel Dynan, a managing principal at Meketa Investment Group, Plymouth County’s investment consultant. “The difference in Plymouth is the magnitude of the change.”

With only 10,500 members, the fund is an unlikely trendsetter. U.S. public pensions guarantee retirement and benefit payments to 34 million members nationally, according to data from the Urban Institute, a nonprofit think tank. Plymouth County, which lies south of Boston, encompasses mostly middle-class suburbs, but also some wealthy enclaves and gritty urban areas. It is split between Democratic and Republican voters.

A decade ago, Plymouth County had only about half of the money it needed to make expected payments for its retirees. An accounting change in 2012 drastically widened shortfalls for most public pensions across the country.

At the same time, the board overseeing the fund, which had spent years relying solely on an outside consultant, was dissatisfied with its investment performance. The approach resembled the classic mix of 60% stocks and 40% bonds popular with ordinary investors.

“We were doing what everyone else was doing, running a 60-40 portfolio and hoping for the best,” said Tom O’Brien, Plymouth County’s treasurer and chairman of the pension board.

The county hired Manning to advise the board on investment strategy in 2012. He had never managed a pension fund before.

“I was a schoolteacher [in the 1980s] in a suburb of Boston and one day, after staring at 20 vacuous stares, I had a talk with my Uncle Bill, a currency trader,” Manning said.

He spent two decades trading commodity futures at his uncle’s brokerage in Boston and stocks at brokerages in Chicago. Then he became a financial adviser to wealthy individuals and families at Merrill Lynch on Cape Cod.

The job at Plymouth County involved a small pay cut, but offered the opportunity to run a nine-figure portfolio for public employees. He got a taste of how painful rising rates could be in May 2013, when comments by Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke sent bond prices tumbling in what became known as the “taper tantrum.”

“We lost $20 million in three trading days and it took us 36 months of clipping coupons to make that back,” Manning said. Coupons are the interest payments bondholders receive.

Initially, Manning and O’Brien focused on boosting alternative investments such as private equity and infrastructure, which made up less than 5% of the fund. They were part of a flock of pension funds seeking alternative investments for higher returns .

Plymouth County hired Meketa as a consultant in 2015, and private-equity and infrastructure investments climbed to nearly 15% by 2020, according to fund financial reports. Returns improved.

“They have a level of comfort being different,” said Dynan.

Markets were on a tear the following year, lifted by the economy’s reopening from the pandemic. But Manning grew concerned in the summer about inflation. While many on Wall Street were calling price increases transitory, he worried inflation would persist, triggering rate increases and declines in stocks and bonds.

“We were going to conferences and being told that inflation was a paper tiger, or ‘this is not your father’s inflation,’” O’Brien said.

Manning consulted Bob Sydow, a high-yield bond fund manager at Mesirow who manages part of the pension’s money. Like Manning, he has worked on Wall Street since the 1980s.

“The money supply grew 43% over 26 months during Covid,” Sydow said. “I called it ‘free-range’ money and I thought it would generate a lot of inflation.”

From October 2021 to February 2022, Plymouth County pension sold about $80 million of its public stocks, or 6% of the fund’s assets, according to an email viewed by The Wall Street Journal. It shifted into real estate and infrastructure as well as short-term and floating-rate debt that is less sensitive to rising rates than traditional bonds, Manning said.

The fund lost 6.5% in 2022 while the median U.S. pension plan lost 14%. That outperformance has helped it stay ahead of other funds, even after it lagged behind the average in 2023.

Now, inflation remains above the Fed’s targets , and analysts’ forecasts for multiple rate cuts this year seem less certain. Plymouth County is keeping its strategy relatively unchanged, betting that rates will remain steady—or even climb.

Many investors are buying back into bonds because yields are at multiyear highs and they expect cuts by the Fed to trigger a rally. Manning takes a different tack. He thinks rates could stay high far longer than the Wall Street consensus, so he is using infrastructure funds to deliver income rather than bonds.

“Why do you have to own bonds at all in 2024?” Manning said. “It’s a legitimate question.”

What a quarter-million dollars gets you in the western capital.

Alexandre de Betak and his wife are focusing on their most personal project yet.

CIOs can take steps now to reduce risks associated with today’s IT landscape

As tech leaders race to bring Windows systems back online after Friday’s software update by cybersecurity company CrowdStrike crashed around 8.5 million machines worldwide, experts share with CIO Journal their takeaways for preparing for the next major information technology outage.

IT leaders should hold vendors deeply integrated within IT systems, such as CrowdStrike , to a “very high standard” of development, release quality and assurance, said Neil MacDonald , a Gartner vice president.

“Any security vendor has a responsibility to do extensive regression testing on all versions of Windows before an update is rolled out,” he said.

That involves asking existing vendors to explain how they write software, what testing they do and whether customers may choose how quickly to roll out an update.

“Incidents like this remind all of us in the CIO community of the importance of ensuring availability, reliability and security by prioritizing guardrails such as deployment and testing procedures and practices,” said Amy Farrow, chief information officer of IT automation and security company Infoblox.

While automatically accepting software updates has become the norm—and a recommended security practice—the CrowdStrike outage is a reminder to take a pause, some CIOs said.

“We still should be doing the full testing of packages and upgrades and new features,” said Paul Davis, a field chief information security officer at software development platform maker JFrog . undefined undefined Though it’s not feasible to test every update, especially for as many as hundreds of software vendors, Davis said he makes it a priority to test software patches according to their potential severity and size.

Automation, and maybe even artificial intelligence-based IT tools, can help.

“Humans are not very good at catching errors in thousands of lines of code,” said Jack Hidary, chief executive of AI and quantum company SandboxAQ. “We need AI trained to look for the interdependence of new software updates with the existing stack of software.”

An incident rendering Windows computers unusable is similar to a natural disaster with systems knocked offline, said Gartner’s MacDonald. That’s why businesses should consider natural disaster recovery plans for maintaining the resiliency of their operations.

One way to do that is to set up a “clean room,” or an environment isolated from other systems, to use to bring critical systems back online, according to Chirag Mehta, a cybersecurity analyst at Constellation Research.

Businesses should also hold tabletop exercises to simulate risk scenarios, including IT outages and potential cyber threats, Mehta said.

Companies that back up data regularly were likely less impacted by the CrowdStrike outage, according to Victor Zyamzin, chief business officer of security company Qrator Labs. “Another suggestion for companies, and we’ve been saying that again and again for decades, is that you should have some backup procedure applied, running and regularly tested,” he said.

For any vendor with a significant impact on company operations , MacDonald said companies can review their contracts and look for clauses indicating the vendors must provide reliable and stable software.

“That’s where you may have an advantage to say, if an update causes an outage, is there a clause in the contract that would cover that?” he said.

If it doesn’t, tech leaders can aim to negotiate a discount serving as a form of compensation at renewal time, MacDonald added.

The outage also highlights the importance of insurance in providing companies with bottom-line protection against cyber risks, said Peter Halprin, a partner with law firm Haynes Boone focused on cyber insurance.

This coverage can include protection against business income losses, such as those associated with an outage, whether caused by the insured company or a service provider, Halprin said.

The CrowdStrike update affected only devices running Microsoft Windows-based systems , prompting fresh questions over whether enterprises should rely on Windows computers.

CrowdStrike runs on Windows devices through access to the kernel, the part of an operating system containing a computer’s core functions. That’s not the same for Apple ’s Mac operating system and Linux, which don’t allow the same level of access, said Mehta.

Some businesses have converted to Chromebooks , simple laptops developed by Alphabet -owned Google that run on the Chrome operating system . “Not all of them require deeper access to things,” Mehta said. “What are you doing on your laptop that actually requires Windows?”