Money Angst? You Might Consider a Financial Therapist

Unconscious beliefs and emotions can mess up how people handle their finances. The hard part is finding experts qualified to handle both money and the mind.

Unconscious beliefs and emotions can mess up how people handle their finances. The hard part is finding experts qualified to handle both money and the mind.

Do you worry a lot about higher food and gas bills? Fight with your spouse over spending splurges? Fear you’ll outlive your savings?

Some people seek to ease such money anxieties by hiring a financial therapist.

The goal of financial therapists ultimately is to help people make good financial decisions, typically by raising their clients’ awareness of how their emotions and unconscious beliefs have affected their sometimes messy experiences with money.

Needs for such help often arise following a job loss, bankruptcy or marital partner’s financial infidelity—when one spouse hides or misrepresents financial information from the other. Even something seemingly positive, such as getting a big inheritance or winning a lottery, can cause financial anxiety.

“Folks are craving help with financial well-being,’’ says Ashley Agnew , president of the Financial Therapy Association, a professional group launched in 2009.

Financial therapists tend to come from mental-health and financial-planning disciplines, and there are signs that their ranks are rising: The Financial Therapy Association has 430 members, up from 225 in 2015. Still, according to the group, fewer than 100 financial therapists have completed its certification process, introduced in 2019. You can be an association member without being certified by it.

The reason for the increased interest is clear: Many Americans are worried about their personal finances. In a survey of about 3,000 U.S. adults conducted last October by Fidelity Investments, more than one-third of respondents said they were in “worse financial shape” than in the previous year. Some 55% of those respondents blamed inflation and cost-of-living increases.

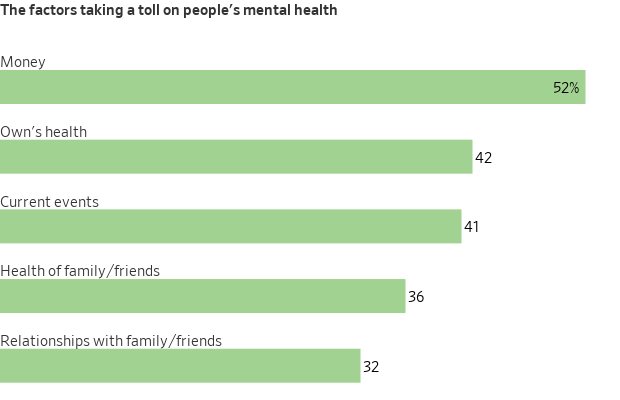

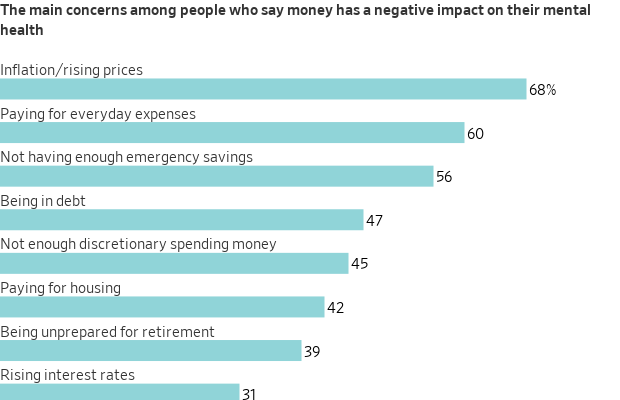

Similarly, 52% of 2,365 Americans polled for Bankrate.com said money negatively affected their mental health in 2023. That is 10 percentage points higher than in 2022. Financially anxious and stressed individuals are less likely to plan for retirement, prior research has concluded.

New York advisory firm Francis Financial hired financial therapist Allen Sakon last November to aid individual clients. Many are divorced or widowed women with complicated money problems.

Certain clients “don’t believe they have enough resources, even though objectively they do,” says Sakon, who is a certified financial therapist, financial planner and accountant. Meanwhile, others with limited means mistakenly believe “they can live as extravagantly as they want,’’ she says.

Sakon currently counsels a recently divorced woman who is struggling with her dramatically lower income and the imminent sale of the family’s suburban New York home. “Her world has been turned upside down” by a financially messy divorce, Sakon says.

Though the woman has stressful new money responsibilities, she long avoided financial decisions, according to Sakon. “A money-avoidant grown-up is typically someone who was excluded from money discussions as a child,” she says.

Sakon says she hopes to eventually help this client feel capable of making financial decisions based on her resources and the financial plan that Sakon created for her.

Nate Astle , a certified financial therapist in Kansas City, Mo., met nine times from May 2023 to February 2024 with Andrea and Gianluca Presti , a 30-something Texas couple who were having persistent spats over money. Andrea Presti , an email marketer, says she believed that “if we didn’t go to financial therapy, I was going to question our entire relationship and whether we could continue.”

The wife cites an argument over the possible purchase of an expensive new car to replace their decade-old vehicle as an example of the couple’s financial conflicts. They disagreed over whether to give up a car that still worked well.

The husband, Gianluca Presti, a music producer, says financial therapy taught him and his wife to communicate better through active listening. He says he stopped being the couple’s money gatekeeper, became more open-minded about spending—and agreed to pay up to $45,000 cash for a new car. “We have to be a team if we want to solve financial issues,” he now realises.

Astle helped the Prestis revamp their household budget as well. It now reflects each spouse’s interests by including expenditures, investments and savings.

Astle, who is also a marriage and family therapist, says he has seen his financial-therapy clients more than double to 43 since 2022.

Still, there are possible pitfalls when hiring a financial therapist. One major drawback: Anyone can claim they are qualified to practice financial therapy.

No government agency regulates the young profession. Candidates for certification by the Financial Therapy Association must take online courses designed by the association covering financial and therapeutic techniques, counsel clients for 250 hours and pass a 100-question test. But you can call yourself a financial therapist and not be certified by the association.

Meanwhile, the cost of financial therapy varies widely—from $125 to $350 an hour, Agnew estimates. Insurance rarely covers the tab.

In addition, there is no broad evidence that financial therapy works well. No large-scale studies demonstrating the field’s effectiveness have been conducted.

Another potential downside is that financial therapists with mental-health backgrounds typically lack extensive financial-planning experience—and vice versa. It is wise to interview at least three financial therapists, experts suggest. Then, pick someone who admits the limits of their expertise.

“I am very upfront about my boundaries,” says practitioner Aja Evans , a licensed mental-health counsellor who isn’t certified in financial therapy. Evans adds that she failed the certification test but plans to take it again during 2024—and before she becomes Financial Therapy Association president in January.

She says she feels well-qualified to help clients recognise how their upbringing affects their money beliefs today. “But I am in no shape or form going to be advising you about your investments, money moves or creating a financial plan,” Evans says. For clients who want that assistance, she says, she refers them to certified financial planners and accountants she knows well.

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

What a quarter-million dollars gets you in the western capital.

Alexandre de Betak and his wife are focusing on their most personal project yet.

Multinationals like Starbucks and Marriott are taking a hard look at their Chinese operations—and tempering their outlooks.

For years, global companies showcased their Chinese operations as a source of robust growth. A burgeoning middle class, a stream of people moving to cities, and the creation of new services to cater to them—along with the promise of the further opening of the world’s second-largest economy—drew companies eager to tap into the action.

Then Covid hit, isolating China from much of the world. Chinese leader Xi Jinping tightened control of the economy, and U.S.-China relations hit a nadir. After decades of rapid growth, China’s economy is stuck in a rut, with increasing concerns about what will drive the next phase of its growth.

Though Chinese officials have acknowledged the sputtering economy, they have been reluctant to take more than incremental steps to reverse the trend. Making matters worse, government crackdowns on internet companies and measures to burst the country’s property bubble left households and businesses scarred.

Now, multinational companies are taking a hard look at their Chinese operations and tempering their outlooks. Marriott International narrowed its global revenue per available room growth rate to 3% to 4%, citing continued weakness in China and expectations that demand could weaken further in the third quarter. Paris-based Kering , home to brands Gucci and Saint Laurent, posted a 22% decline in sales in the Asia-Pacific region, excluding Japan, in the first half amid weaker demand in Greater China, which includes Hong Kong and Macau.

Pricing pressure and deflation were common themes in quarterly results. Starbucks , which helped build a coffee culture in China over the past 25 years, described it as one of its most notable international challenges as it posted a 14% decline in sales from that business. As Chinese consumers reconsidered whether to spend money on Starbucks lattes, competitors such as Luckin Coffee increased pressure on the Seattle company. Starbucks executives said in their quarterly earnings call that “unprecedented store expansion” by rivals and a price war hurt profits and caused “significant disruptions” to the operating environment.

Executive anxiety extends beyond consumer companies. Elevator maker Otis Worldwide saw new-equipment orders in China fall by double digits in the second quarter, forcing it to cut its outlook for growth out of Asia. CEO Judy Marks told analysts on a quarterly earnings call that prices in China were down roughly 10% year over year, and she doesn’t see the pricing pressure abating. The company is turning to productivity improvements and cost cutting to blunt the hit.

Add in the uncertainty created by deteriorating U.S.-China relations, and many investors are steering clear. The iShares MSCI China exchange-traded fund has lost half its value since March 2021. Recovery attempts have been short-lived. undefined undefined And now some of those concerns are creeping into the U.S. market. “A decade ago China exposure [for a global company] was a way to add revenue growth to our portfolio,” says Margaret Vitrano, co-manager of large-cap growth strategies at ClearBridge Investments in New York. Today, she notes, “we now want to manage the risk of the China exposure.”

Vitrano expects improvement in 2025, but cautions it will be slow. Uncertainty over who will win the U.S. presidential election and the prospect of higher tariffs pose additional risks for global companies.

For now, China is inching along at roughly 5% economic growth—down from a peak of 14% in 2007 and an average of about 8% in the 10 years before the pandemic. Chinese consumers hit by job losses and continued declines in property values are rethinking spending habits. Businesses worried about policy uncertainty are reluctant to invest and hire.

The trouble goes beyond frugal consumers. Xi is changing the economy’s growth model, relying less on the infrastructure and real estate market that fueled earlier growth. That means investing aggressively in manufacturing and exports as China looks to become more self-reliant and guard against geopolitical tensions.

The shift is hurting western multinationals, with deflationary forces amid burgeoning production capacity. “We have seen the investment community mark down expectations for these companies because they will have to change tack with lower-cost products and services,” says Joseph Quinlan, head of market strategy for the chief investment office at Merrill and Bank of America Private Bank.

Another challenge for multinationals outside of China is stiffened competition as Chinese companies innovate and expand—often with the backing of the government. Local rivals are upping the ante across sectors by building on their knowledge of local consumer preferences and the ability to produce higher-quality products.

Some global multinationals are having a hard time keeping up with homegrown innovation. Auto makers including General Motors have seen sales tumble and struggled to turn profitable as Chinese car shoppers increasingly opt for electric vehicles from BYD or NIO that are similar in price to internal-combustion-engine cars from foreign auto makers.

“China’s electric-vehicle makers have by leaps and bounds surpassed the capabilities of foreign brands who have a tie to the profit pool of internal combustible engines that they don’t want to disrupt,” says Christine Phillpotts, a fund manager for Ariel Investments’ emerging markets strategies.

Chinese companies are often faster than global rivals to market with new products or tweaks. “The cycle can be half of what it is for a global multinational with subsidiaries that need to check with headquarters, do an analysis, and then refresh,” Phillpotts says.

For many companies and investors, next year remains a question mark. Ashland CEO Guillermo Novo said in an August call with analysts that the chemical company was seeing a “big change” in China, with activity slowing and competition on pricing becoming more aggressive. The company, he said, was still trying to grasp the repercussions as it has created uncertainty in its 2025 outlook.

Few companies are giving up. Executives at big global consumer and retail companies show no signs of reducing investment, with most still describing China as a long-term growth market, says Dana Telsey, CEO of Telsey Advisory Group.

Starbucks executives described the long-term opportunity as “significant,” with higher growth and margin opportunities in the future as China’s population continues to move from rural to suburban areas. But they also noted that their approach is evolving and they are in the early stages of exploring strategic partnerships.

Walmart sold its stake in August in Chinese e-commerce giant JD.com for $3.6 billion after an eight-year noncompete agreement expired. Analysts expect it to pump the money into its own Sam’s Club and Walmart China operation, which have benefited from the trend toward trading down in China.

“The story isn’t over for the global companies,” Phillpotts says. “It just means the effort and investment will be greater to compete.”

Corrections & Amplifications

Joseph Quinlan is head of market strategy for the chief investment office at Merrill and Bank of America Private Bank. An earlier version of this article incorrectly used his old title.