More Americans Than Ever Own Stocks

Pandemic, zero-commission trading ‘created a whole generation of investors’

Pandemic, zero-commission trading ‘created a whole generation of investors’

The share of Americans who own stocks has never been so high.

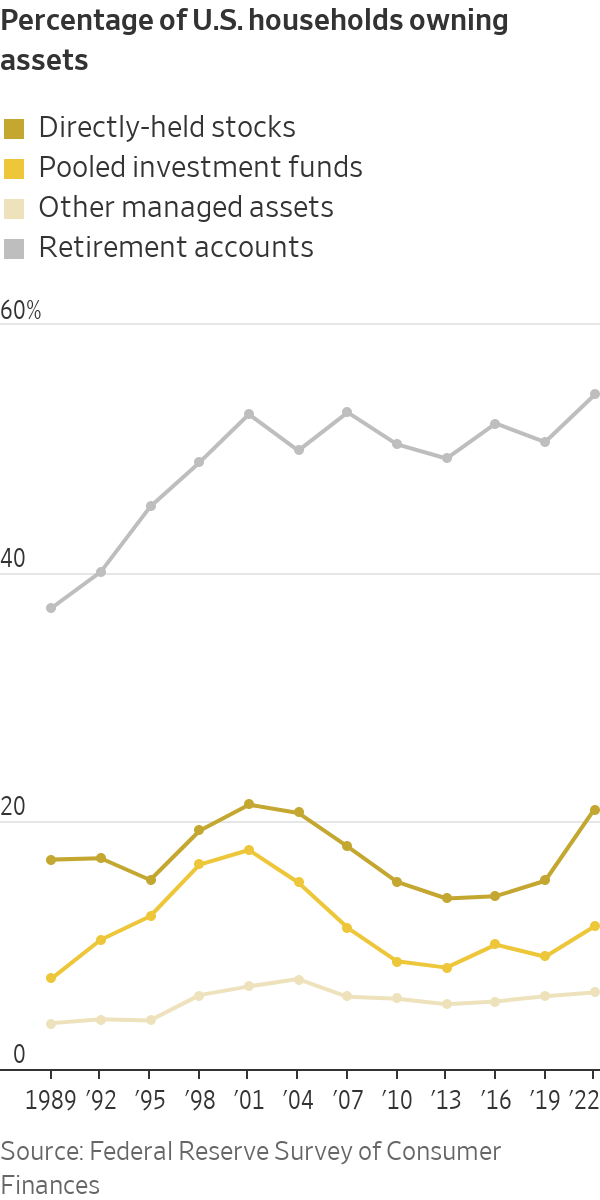

About 58% of U.S. households owned stocks in 2022, according to the Federal Reserve’s survey of consumer finances released this fall. That is up from 53% in 2019 and marks the highest household stock-ownership rate recorded in the triennial survey. The cohort includes families holding individual shares directly and those owning stocks indirectly through funds, retirement accounts or other managed accounts.

The data provide the most comprehensive snapshot yet of how the Covid-era explosion in investing has reshaped Americans’ personal finances. Stuck at home during the pandemic with extra cash, millions jumped into the stock market for the first time. The elimination of commission fees on stock trading across U.S. brokerages made investing cheaper than ever.

“It created a whole generation of investors,” said Anthony Denier, chief executive of mobile brokerage Webull U.S.

Most households own stocks through a retirement account, such as a 401(k), but more Americans in the past few years have invested in individual shares directly. Direct stock ownership increased to 21% of families in 2022 from 15% in 2019—the largest increase on record since the survey began in 1989.

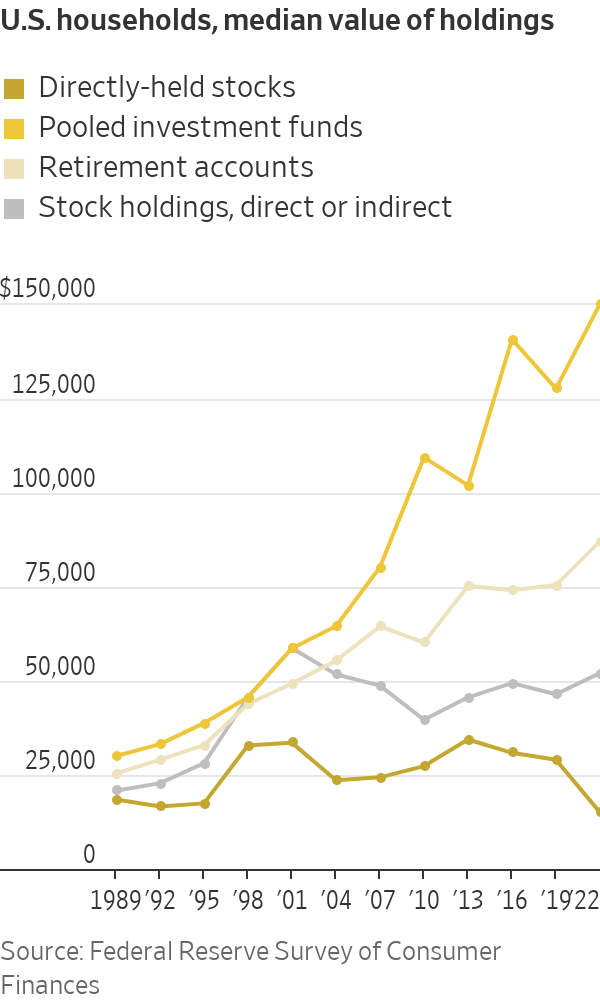

As more households bought individual shares, those newer entrants invested with less money than longtime stockholders. The median value of households’ direct stockholdings nearly halved from 2019 to about $15,000 in 2022, adjusted for inflation.

When the stock market crashed in early 2020, Nick Luczak, then a sophomore at the University of Michigan, used the $57 in his checking account to open a brokerage account on Robinhood and buy whichever stocks he could afford. Once the pandemic forced him off campus to live with his parents, he began researching the market and buying more stocks.

“I said, ‘Well, I have all this spare time. There’s no reason at all I shouldn’t be trying to make the most money possible from this,’” Luczak said.

Luczak and his fraternity brothers started a group chat to discuss markets and stock picks. He said he made a profit investing in Amazon.com and watched his friends make, then lose, thousands of dollars trading meme stocks such as GameStop and AMC Entertainment Holdings in 2021. At one point, he considered becoming a day trader.

Now, Luczak, 24 years old, is focused on long-term investing. A salesman in Dallas, he is studying to become a certified financial planner.

Brokerages in recent years have made trading free and easy. Newer apps like Robinhood and Webull helped popularise zero-commission stock trading on smartphones. Charles Schwab, TD Ameritrade and E*Trade all eliminated commission fees for stocks at the end of 2019. Fidelity and Schwab introduced fractional stock trading in 2020, allowing individuals to buy and sell slivers of shares.

“It’s become more accessible,” said Ashley Feinstein Gerstley, a certified financial planner and founder of The Fiscal Femme. “We’ve been debunking in the last few years the myth that you have to be rich or work on Wall Street to invest.”

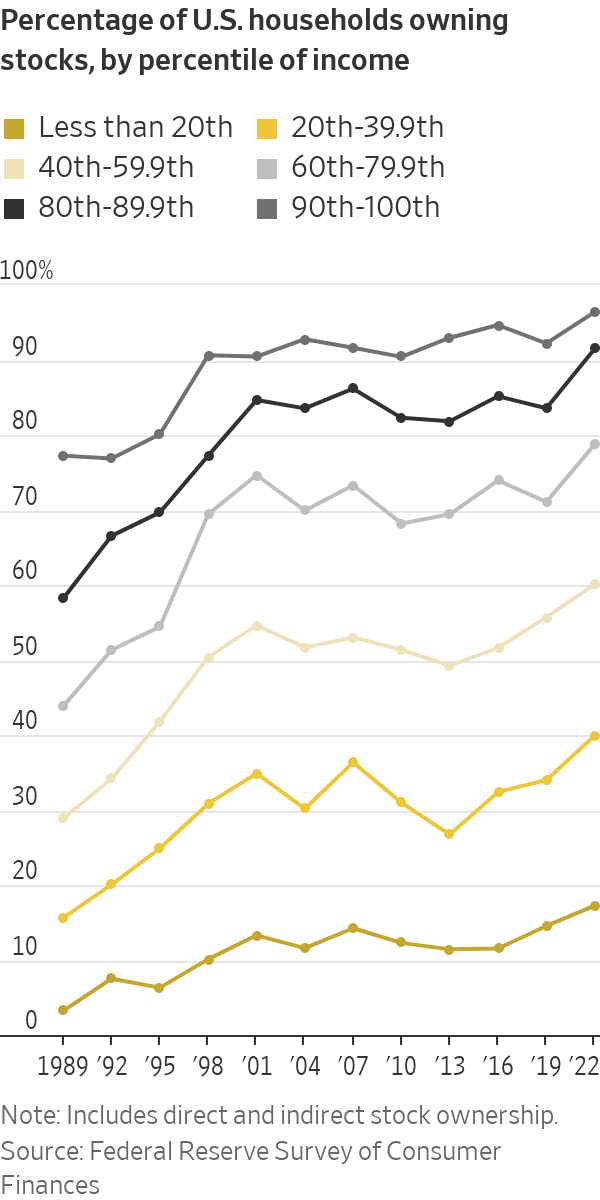

The share of households owning stocks increased across all income levels from 2019 to 2022. Upper-middle-income families recorded the biggest jump in stock ownership.

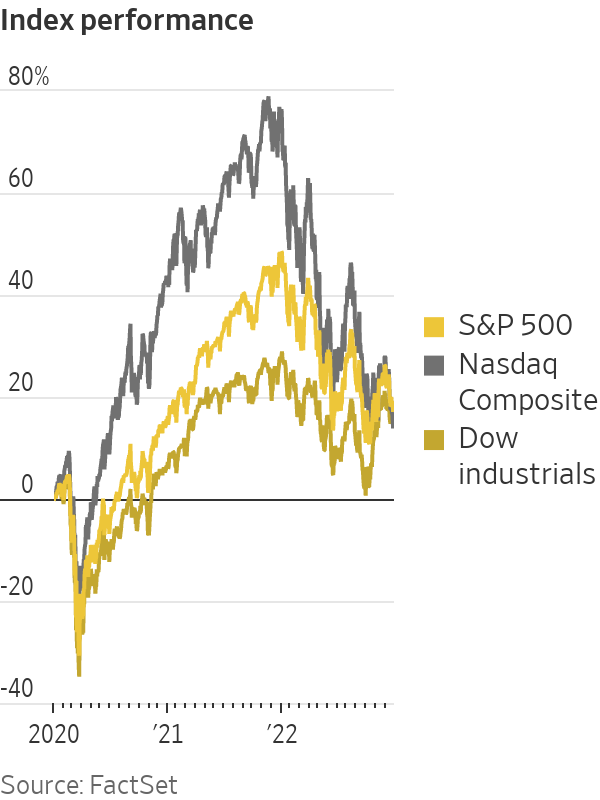

Over those three years, stocks climbed to new highs. The S&P 500 rose 16% in 2020 and 27% in 2021. Even after a 19% drop last year, the benchmark stock index notched gains over the three-year period. The S&P 500 is up 23% in 2023.

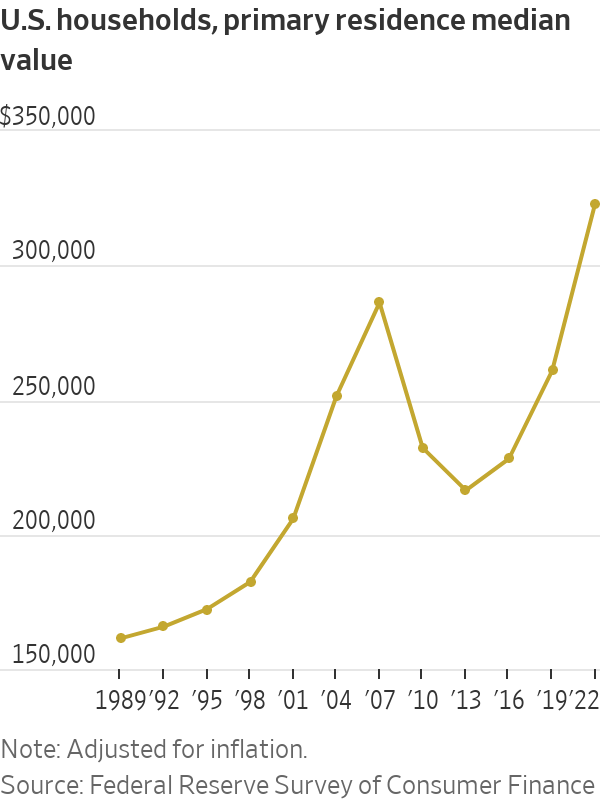

Stock-market gains and rising home prices helped boost household wealth. Households’ median net worth climbed 37% from 2019 to 2022, adjusted for inflation, the largest increase in the survey’s history. The median value of a U.S. household’s primary residence surged to $323,200 in 2022, surpassing levels from before the 2007 housing market crash.

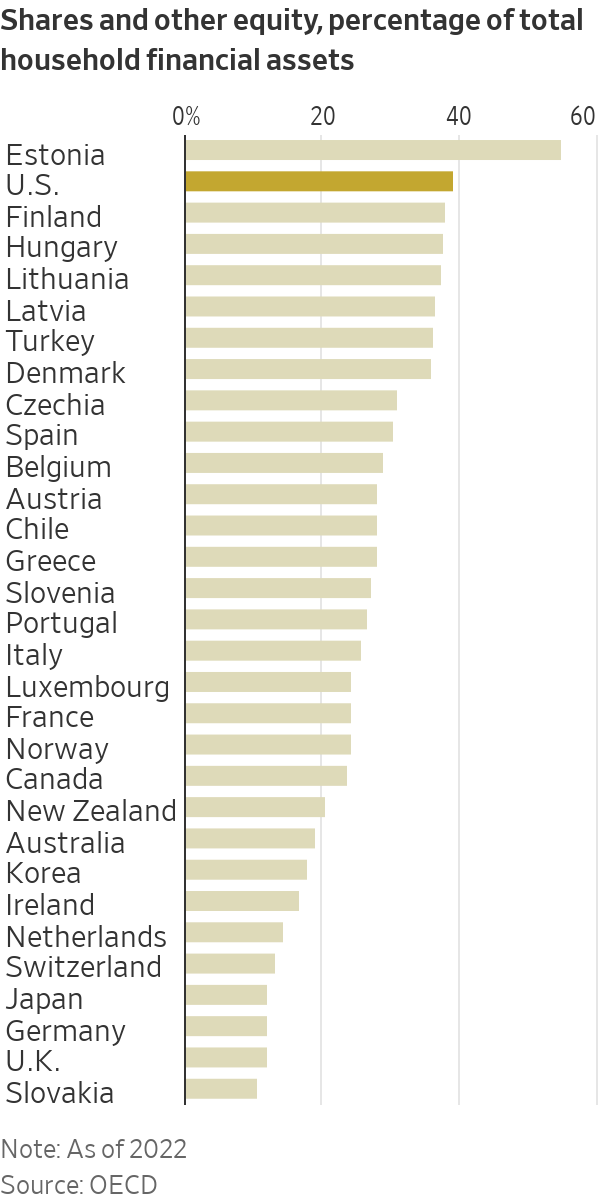

Americans’ penchant for stocks is distinct. U.S. households held about 39% of their financial assets in equities in 2022, according to Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development data, a higher allocation than most other countries in the data set.

That appetite for stocks has been tested since the Fed began raising interest rates last year at the fastest clip since the 1980s and pledged to keep rates higher for longer. Investors have been flocking to assets with little risk such as money-market funds that are now offering some of the highest yields in years. Everyday investors, who rarely own bonds directly, are taking a second look at assets such as Treasurys and corporate bonds.

Fernando Soto, head of private banking in Chicago at Brown Brothers Harriman, said he has fielded more questions from clients about fixed-income investing and more requests from clients to buy bonds in 2023. In his personal portfolio, he increased his allocation to fixed-income this year.

“There’s a big shift,” Soto said. “This is the new normal.”

How has the higher rate environment shifted American household finances? The Fed consumer finance survey in 2025 will likely paint the fullest picture.

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

What a quarter-million dollars gets you in the western capital.

Alexandre de Betak and his wife are focusing on their most personal project yet.

CIOs can take steps now to reduce risks associated with today’s IT landscape

As tech leaders race to bring Windows systems back online after Friday’s software update by cybersecurity company CrowdStrike crashed around 8.5 million machines worldwide, experts share with CIO Journal their takeaways for preparing for the next major information technology outage.

IT leaders should hold vendors deeply integrated within IT systems, such as CrowdStrike , to a “very high standard” of development, release quality and assurance, said Neil MacDonald , a Gartner vice president.

“Any security vendor has a responsibility to do extensive regression testing on all versions of Windows before an update is rolled out,” he said.

That involves asking existing vendors to explain how they write software, what testing they do and whether customers may choose how quickly to roll out an update.

“Incidents like this remind all of us in the CIO community of the importance of ensuring availability, reliability and security by prioritizing guardrails such as deployment and testing procedures and practices,” said Amy Farrow, chief information officer of IT automation and security company Infoblox.

While automatically accepting software updates has become the norm—and a recommended security practice—the CrowdStrike outage is a reminder to take a pause, some CIOs said.

“We still should be doing the full testing of packages and upgrades and new features,” said Paul Davis, a field chief information security officer at software development platform maker JFrog . undefined undefined Though it’s not feasible to test every update, especially for as many as hundreds of software vendors, Davis said he makes it a priority to test software patches according to their potential severity and size.

Automation, and maybe even artificial intelligence-based IT tools, can help.

“Humans are not very good at catching errors in thousands of lines of code,” said Jack Hidary, chief executive of AI and quantum company SandboxAQ. “We need AI trained to look for the interdependence of new software updates with the existing stack of software.”

An incident rendering Windows computers unusable is similar to a natural disaster with systems knocked offline, said Gartner’s MacDonald. That’s why businesses should consider natural disaster recovery plans for maintaining the resiliency of their operations.

One way to do that is to set up a “clean room,” or an environment isolated from other systems, to use to bring critical systems back online, according to Chirag Mehta, a cybersecurity analyst at Constellation Research.

Businesses should also hold tabletop exercises to simulate risk scenarios, including IT outages and potential cyber threats, Mehta said.

Companies that back up data regularly were likely less impacted by the CrowdStrike outage, according to Victor Zyamzin, chief business officer of security company Qrator Labs. “Another suggestion for companies, and we’ve been saying that again and again for decades, is that you should have some backup procedure applied, running and regularly tested,” he said.

For any vendor with a significant impact on company operations , MacDonald said companies can review their contracts and look for clauses indicating the vendors must provide reliable and stable software.

“That’s where you may have an advantage to say, if an update causes an outage, is there a clause in the contract that would cover that?” he said.

If it doesn’t, tech leaders can aim to negotiate a discount serving as a form of compensation at renewal time, MacDonald added.

The outage also highlights the importance of insurance in providing companies with bottom-line protection against cyber risks, said Peter Halprin, a partner with law firm Haynes Boone focused on cyber insurance.

This coverage can include protection against business income losses, such as those associated with an outage, whether caused by the insured company or a service provider, Halprin said.

The CrowdStrike update affected only devices running Microsoft Windows-based systems , prompting fresh questions over whether enterprises should rely on Windows computers.

CrowdStrike runs on Windows devices through access to the kernel, the part of an operating system containing a computer’s core functions. That’s not the same for Apple ’s Mac operating system and Linux, which don’t allow the same level of access, said Mehta.

Some businesses have converted to Chromebooks , simple laptops developed by Alphabet -owned Google that run on the Chrome operating system . “Not all of them require deeper access to things,” Mehta said. “What are you doing on your laptop that actually requires Windows?”