Nike Reverses Course as Innovation Stalls and Rivals Gain Ground

Shoe giant stumbled as CEO John Donahoe pulled away from retailers and relied on old hits. Now it says it’s refocusing on cutting-edge footwear for athletes.

Shoe giant stumbled as CEO John Donahoe pulled away from retailers and relied on old hits. Now it says it’s refocusing on cutting-edge footwear for athletes.

In late February, Nike boss John Donahoe led a virtual all-hands meeting where he delivered a message to his staff: The company wasn’t performing at its best and he held himself accountable.

Two weeks earlier, Nike had announced it would lay off more than 1,600 employees .

Now, as the CEO spoke at the meeting, critical comments started to fill the chat window on the Zoom call while more than 20,000 employees watched.

“Accountability: I do not think that word means what you think it means,” an employee wrote. “If this is cost cutting, how about a CEO salary cut?” another wrote. Soon a cascade of laughing emojis filled the screen.

Some colleagues warned others that their posts weren’t anonymous and the chat might be monitored. The attacks went on for several minutes. “I hope Phil is watching and reading this,” an employee wrote, referencing the retired Nike co-founder Phil Knight .

The virtual protest illustrated the depths of the dissatisfaction within the sneaker giant and concern for its strategy. “How did we actually get here?” wrote one product manager.

Since the pandemic, Nike has lost ground in its critical running category while it focused on pumping out old hits and preparing for an e-commerce revolution that never came. The moves, current and former employees say, have eroded a culture of innovation and edginess that made Nike one of the world’s best-known brands.

Donahoe had told The Wall Street Journal in 2020 that his No. 1 priority when taking over the company was “don’t screw it up.” Four years later, the company is unwinding key elements of the CEO’s strategy that have backfired as a growing number of upstarts nip at its heels.

Among the reversals: As Covid raged and more shopping moved online, Nike cut ties with longtime retail partners such as DSW and Urban Outfitters and tried selling more merchandise directly to consumers. It is now asking some of those stores for help clearing out its overstuffed shelves and warehouses.

“I would say we got some things right and some things wrong,” Donahoe said Thursday, in an interview at Nike’s Beaverton, Ore., headquarters.

The strategic missteps have animated a debate inside the company about its identity. In its zeal to boost digital sales, some current and former employees say, Nike veered from its roots as a maker of cutting-edge footwear for serious athletes. It has opened itself to competition from newcomers such as On and Hoka, which have borrowed from the playbook that fuelled Nike’s rise—including focusing on sport over lifestyle, and taking risks on innovation.

Nike’s once torrid growth has stalled . Sales for the quarter ended Feb. 29 were flat compared with a year earlier, and shares in the company have declined 24% over the past year, compared with a 19% gain in the S&P 500.

Donahoe in the interview acknowledged the brand lost its “sharp edge” in sports and needed to boost its “disruptive innovation pipeline.” The CEO said the brand’s marketing got fragmented and that with people going back to bricks-and-mortar stores, it was clear Nike needed to invest in its retail partners.

Nike executives said in interviews that the company became too cautious after the pandemic and overly reliant on older products that were reliable sellers. They said the company has made significant changes in recent months to refocus it on putting out cutting-edge footwear.

“We were serving consumers what they know and love,” said John Hoke , Nike’s recently named chief innovation officer. “The job is to of course do that but also to show them something new, take them someplace new.”

Donahoe said Nike is going through a period of adversity and layoffs that has created uncertainty, but that the company will get through it. “Our employees have been through a lot,” he said. “Nike is actually at its best, like a great sports team, when our backs are against the wall.”

Knight, who is chairman emeritus of the board and the company’s largest shareholder, said in a statement that Donahoe has his “unwavering support.”

Donahoe said employees’ responses to the all-hands meeting reflected one of Nike’s biggest strengths: how much its staff cares about the company. “We welcome and encourage that,” Donahoe said.

Donahoe took over Nike just before the pandemic, at a delicate time. Though he inherited a market leader and one of the world’s best-known brands, Nike was seeking a refresh after it dealt with complaints about its workplace culture that led to a management shake-up .

The Evanston, Ill., native had been CEO of eBay , where he doubled the e-commerce platform’s revenue during a seven-year stint that ended in 2015. After a sabbatical—during which he says he had a life-altering experience at a 10-day Buddhist silent meditation retreat—Donahoe went on to run cloud-computing company ServiceNow .

When he took the helm of Nike in early 2020, his marching orders from Mark Parker , his predecessor and current executive chairman, and Knight were clear. He was to turn the world’s biggest shoe maker into a tech company more directly connected to consumers through its own apps, which in turn collect valuable data from shoppers.

Parker said when he stepped down that Donahoe was the right candidate to lead Nike’s digital transformation.

Donahoe was just the fourth CEO in the company’s more than 50-year history. The only other outsider to get the job said he was ousted in 2006 after a short stint because he focused too much on the numbers .

Donahoe started out with a 100-day global listening tour that was cut short after a month when the pandemic hit.

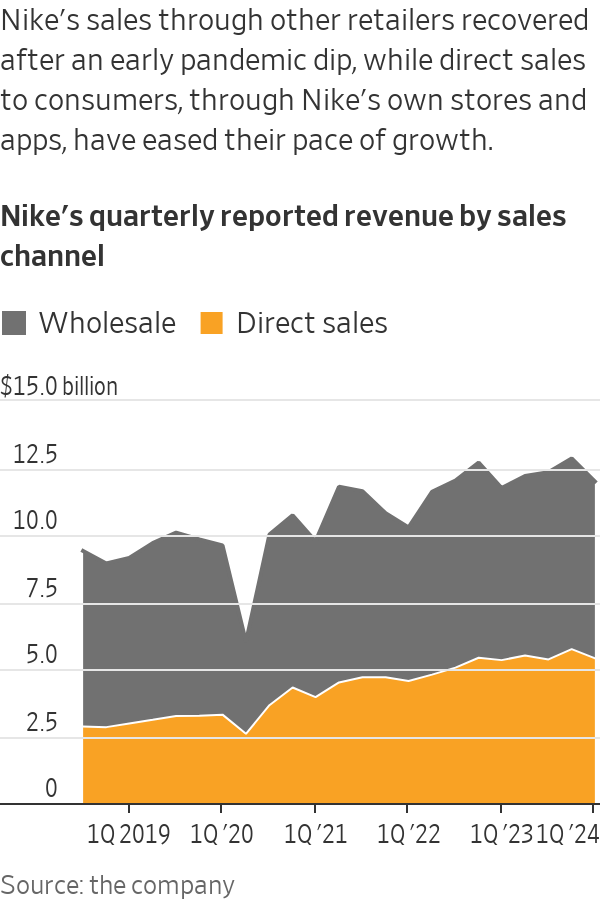

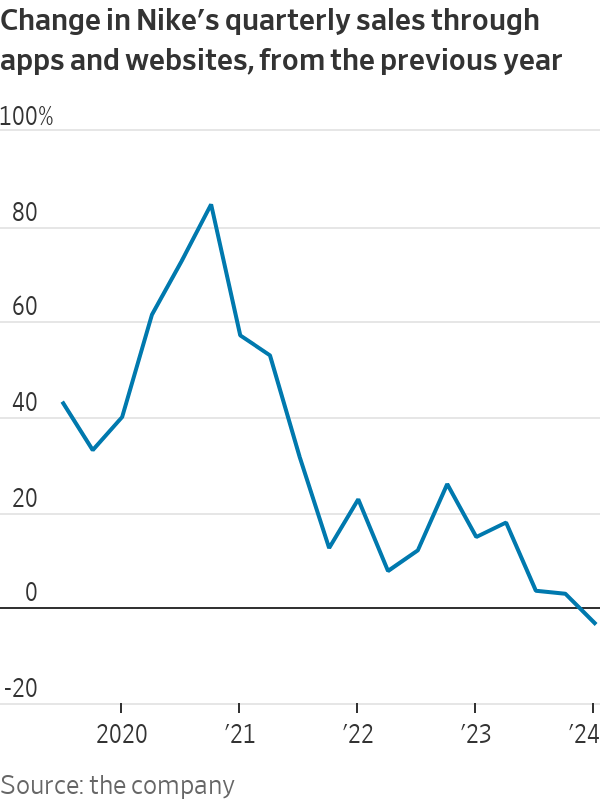

Covid lockdowns fueled a surge in online shopping. Digital channels accounted for 30% of Nike’s sales in May 2020, about three years ahead of schedule.

Donahoe saw it as an acceleration of an inevitable shift and adjusted Nike’s plans accordingly. A few months in, he redoubled the company’s bet that it could make more money by selling products directly to consumers through its stores and digital channels. He said he believed digital sales would reach 50% of the business, and Nike should transform faster to define the marketplace of the future. It was time to act.

By late 2020, Nike dropped about a third of its sales partners and sold less merchandise to clients such as Foot Locker , DSW and Macy’s . There had been a plan to phase out wholesale clients since 2017, but with digital sales growing quickly, Donahoe said there was a need for urgency.

Executives were divided over whether Nike’s own stores, which include both factory outlets and specialty shops selling higher-priced new releases, could fill the sales void left by the retailers the company was cutting out.

In meetings, finance chief Matt Friend and Nike president Heidi O’Neill supported the aggressive exit from retail that Donahoe was pushing, while others favoured a slower transition, people familiar with the matter said.

Some executives felt the specialty stores in particular worked better as marketing tools and that cutting off so many retailers so fast would backfire, the people said. Donahoe and his allies prevailed.

Nike teams were tasked to come up with a new global supply-chain process. Selling directly to consumers increased the company’s liabilities, including by shifting storage and shipping costs from wholesalers to Nike. The company would also absorb the losses from discounts if the merchandise didn’t sell quickly and inventory piled up.

One of the casualties of Donahoe’s 2020 transformation was a multibillion-dollar operation dedicated to developing footwear sold for under $100. The company deprioritised more-affordable footwear that usually sold to the sales partners that Nike was leaving behind. The move left Nike skewed toward higher-priced shoes.

The first evidence of cracks in Nike’s new approach appeared early last year when Foot Locker Chief Executive Mary Dillon said during an earnings call the brand had reversed course and was sending the retailer a wider assortment of Nike products. By the summer, Macy’s and DSW were saying the same thing.

The message was clear: Nike needed help selling merchandise.

Nike veterans said cutting off wholesale clients was one of the biggest mistakes the company has ever made. After digital sales hit the 30% of the total mark early in the pandemic, they dropped back, and haven’t reached that level since—let alone the 50% target Donahoe had foreseen.

Donahoe said in the interview the goal at the time was to lean more on specific partners, such as Dick’s Sporting Goods and JD Sports , which he considers to be more aligned with Nike, rather than make a dramatic shift in strategy. Nike deprioritised making lower-priced shoes because of supply-chain disruptions during the pandemic, but it is now making more of those products, he said.

“I don’t see it as a reversal of the strategy,” Donahoe said of the return to more retail chains. “I see it as an adjustment.”

Competitors have been using the sneaker giant’s playbook at its expense. Smaller brands like On, Hoka and New Balance have captured significant pieces of the market for both hard-core and everyday runners—and their popularity is spreading to the mainstream.

Often quoting Knight, the Nike co-founder, former employees said the principle always was to first capture the market for hard-core athletes with innovative performance gear, and the casual consumer would follow.

In early February, Hoka owner Deckers Outdoor tapped Nike alums to take over both the parent company and the shoe brand. Hoka had $1.4 billion in sales for the year through March 2023, compared with about $352 million three years earlier.

Hoka didn’t respond to requests for comment.

“When you’re the biggest, there’s always going to be people coming after you,” Donahoe said. Competitors give Nike an incentive to try to understand what consumers want and to figure out how to come up with something bold and different, he said.

Nike still dwarfs its competition . During Donahoe’s tenure, Nike sales have grown 31% to $51 billion in 2023. That is more than double the results of Adidas, its closest competitor by far. New Balance reported sales reached $6.5 billion last year, and upstart On almost hit the $2 billion mark.

The race to hit revenue targets came at a cost for Nike. Executives turned to the brand’s lucrative franchises, including Air Jordan and Dunk, and ramped up the releases. The strategy diluted the exclusivity prized by die-hard Nike sneaker shoppers.

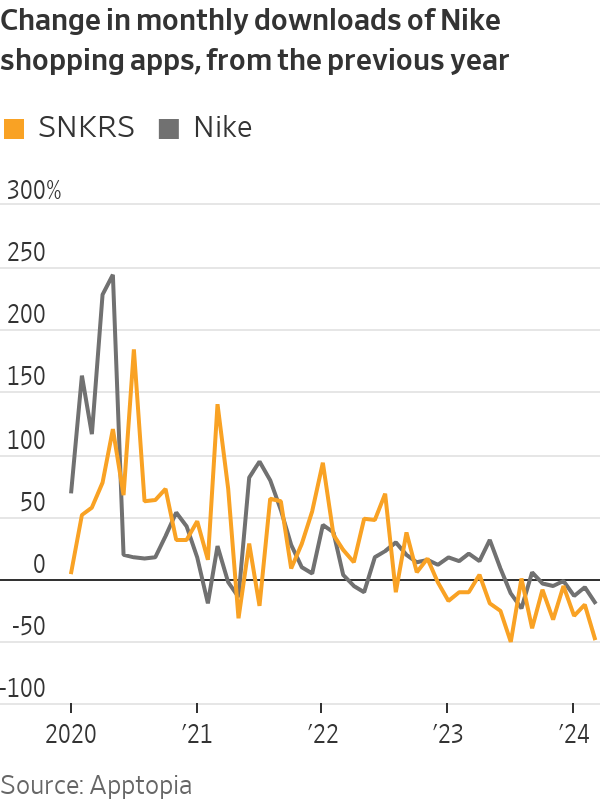

Donahoe said in the interview that Nike ramped up production to meet demand on its SNKRS app, which fans use to buy the latest limited releases. In early 2021, Nike was meeting less than 5% of the demand for some releases on the app and consumers were frustrated, Donahoe said, adding the goal is to meet something closer to 20% of demand for the exclusive styles.

Now, sneaker resellers say they have seen release after release of Nike’s limited-edition kicks that don’t sell out on the SNKRS app, and that in the secondary market—a space that the brand closely monitors —prices are tanking.

Nike executives in March said they would pull back on franchise releases.

Donahoe said “franchise management has always been something Nike has done.”

Nike’s digital sales, a figure that includes direct and partner e-commerce sales, declined for the quarter ended Feb. 29. Friend, the finance chief, told analysts in March that Nike expects total sales to decline at least until the end of this year.

The pursuit of sales growth from limited-edition sneaker releases led Nike to neglect its running category, long considered the core product of the company, former employees said.

This month in Paris, Nike unveiled its new product line for the Olympics, including running shoes with a new cushioning system that uses the company’s Air technology.

In interviews at the event, executives said the company had become somewhat risk-averse during the pandemic, when working remotely stifled creativity. Martin Lotti, chief design officer, said the company had spent too much time looking to its past.

“If you drive a car just by looking in the rear view mirror, that’s not a good thing,” Lotti said. “The bigger opportunity is the windshield.”

Current and former Nike executives believe the future of the company is in its app ecosystem , like the Nike Training and Running Club or its SNKRS app, and the data it can harness from them to help design and sell products. Inside the company, leaders have long tried to draw comparisons to Apple when talking about Nike’s innovation and design culture.

The sneaker giant has been acquiring smaller data analytics startups for at least a decade. Two years ago, it also bet on the NFT craze .

One of Nike’s biggest tech investments is a multibillion-dollar process to migrate multiple software programs into one single system. The new platform, known as S/4HANA, is still not operational and is three years behind schedule. The software is designed to help day-to-day operations, such as procurement and inventory management, and speed up digital sales.

As part of its accelerated focus on digital sales, Nike hired about 3,500 people to join what the company calls its global technology group, which includes consumer insights and data analytics. Executives at the time said they were investing in “demand sensing,” “insight gathering” and a new inventory system.

Former Nike employees with knowledge of the consumer insights strategy said executives misinterpreted the data in ways that overestimated demand for retro franchises.

During February’s round of layoffs executives trimmed layers of management across the company’s insights and analytics teams. A large technology innovation team, tasked with developing software to implement Apple’s new Vision Pro augmented reality system in day-to-day design tasks, and a separate artificial intelligence team were also eliminated.

Executives at Nike say it is entering a “supercycle” of innovation and that the new Air line of products enhances athlete performance.

At the Olympics preview event this month, the company took over the historic Palais Brongniart in central Paris with a three-day event to unveil its new Air line. Guests wandered through a museum-like, conveyor-belt installation highlighting Nike’s product evolutions and research and development programs. Athletes including runners Sha’Carri Richardson and Eliud Kipchoge modeled the new gear. Retired tennis great Serena Williams narrated the company’s lavish introduction video before appearing on stage.

Outside, 30-foot orange statues of Nike-sponsored athletes including LeBron James, Kylian Mbappé and Victor Wembanyama stood guard.

Donahoe’s relationship with Knight goes back to the early 1990s, when he was a Bain consultant on Nike projects. He joined the Nike board in 2014 and is one of the directors of an entity Knight created called Swoosh LLC, which holds roughly $22 billion worth of Nike shares and controls a majority of Nike’s board seats. Donahoe calls Knight his “greatest hero in business.”

The current CEO said he meets with his predecessor, Parker, every week.

Donahoe said that he and Parker share an approach to management he calls “servant leadership” that was embodied by some of his sports heroes, including basketball coaches Phil Jackson, John Thompson, Mike Krzyzewski and Tara VanDerveer.

“It’s never been about me. It’s about your players. And are you doing everything you can to allow your players to make the adjustments to win? And when you have a win it’s about the players and when you have a loss you say it’s on me, right?,” he said. “And that’s what I’ve always tried to embody, including during this period of time.”

This week, Donahoe is facing another test: the company is notifying several hundred more workers whose jobs are being cut.

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

What a quarter-million dollars gets you in the western capital.

Alexandre de Betak and his wife are focusing on their most personal project yet.

CIOs can take steps now to reduce risks associated with today’s IT landscape

As tech leaders race to bring Windows systems back online after Friday’s software update by cybersecurity company CrowdStrike crashed around 8.5 million machines worldwide, experts share with CIO Journal their takeaways for preparing for the next major information technology outage.

IT leaders should hold vendors deeply integrated within IT systems, such as CrowdStrike , to a “very high standard” of development, release quality and assurance, said Neil MacDonald , a Gartner vice president.

“Any security vendor has a responsibility to do extensive regression testing on all versions of Windows before an update is rolled out,” he said.

That involves asking existing vendors to explain how they write software, what testing they do and whether customers may choose how quickly to roll out an update.

“Incidents like this remind all of us in the CIO community of the importance of ensuring availability, reliability and security by prioritizing guardrails such as deployment and testing procedures and practices,” said Amy Farrow, chief information officer of IT automation and security company Infoblox.

While automatically accepting software updates has become the norm—and a recommended security practice—the CrowdStrike outage is a reminder to take a pause, some CIOs said.

“We still should be doing the full testing of packages and upgrades and new features,” said Paul Davis, a field chief information security officer at software development platform maker JFrog . undefined undefined Though it’s not feasible to test every update, especially for as many as hundreds of software vendors, Davis said he makes it a priority to test software patches according to their potential severity and size.

Automation, and maybe even artificial intelligence-based IT tools, can help.

“Humans are not very good at catching errors in thousands of lines of code,” said Jack Hidary, chief executive of AI and quantum company SandboxAQ. “We need AI trained to look for the interdependence of new software updates with the existing stack of software.”

An incident rendering Windows computers unusable is similar to a natural disaster with systems knocked offline, said Gartner’s MacDonald. That’s why businesses should consider natural disaster recovery plans for maintaining the resiliency of their operations.

One way to do that is to set up a “clean room,” or an environment isolated from other systems, to use to bring critical systems back online, according to Chirag Mehta, a cybersecurity analyst at Constellation Research.

Businesses should also hold tabletop exercises to simulate risk scenarios, including IT outages and potential cyber threats, Mehta said.

Companies that back up data regularly were likely less impacted by the CrowdStrike outage, according to Victor Zyamzin, chief business officer of security company Qrator Labs. “Another suggestion for companies, and we’ve been saying that again and again for decades, is that you should have some backup procedure applied, running and regularly tested,” he said.

For any vendor with a significant impact on company operations , MacDonald said companies can review their contracts and look for clauses indicating the vendors must provide reliable and stable software.

“That’s where you may have an advantage to say, if an update causes an outage, is there a clause in the contract that would cover that?” he said.

If it doesn’t, tech leaders can aim to negotiate a discount serving as a form of compensation at renewal time, MacDonald added.

The outage also highlights the importance of insurance in providing companies with bottom-line protection against cyber risks, said Peter Halprin, a partner with law firm Haynes Boone focused on cyber insurance.

This coverage can include protection against business income losses, such as those associated with an outage, whether caused by the insured company or a service provider, Halprin said.

The CrowdStrike update affected only devices running Microsoft Windows-based systems , prompting fresh questions over whether enterprises should rely on Windows computers.

CrowdStrike runs on Windows devices through access to the kernel, the part of an operating system containing a computer’s core functions. That’s not the same for Apple ’s Mac operating system and Linux, which don’t allow the same level of access, said Mehta.

Some businesses have converted to Chromebooks , simple laptops developed by Alphabet -owned Google that run on the Chrome operating system . “Not all of them require deeper access to things,” Mehta said. “What are you doing on your laptop that actually requires Windows?”