Rich Countries Are Becoming Addicted to Cheap Labour

Businesses are relying more on migrant workers as labor shortages persist, but economists warn of long-term dangers

Businesses are relying more on migrant workers as labor shortages persist, but economists warn of long-term dangers

As migration hits record levels worldwide, a debate is building among economists over whether some industries are becoming too dependent on foreign labour.

Many business owners say that bringing in low-skilled foreign workers has become essential, as local populations age and labor forces shrink. In rural Wisconsin, John Rosenow says it is impossible to find locals to work on his 1,000-acre dairy farm. He relies on 13 Mexican immigrants, up from eight to 10 a decade ago. That has enabled him to avoid making costly investments in robots that can help milk cows, as some other dairy farmers have.

“We get really good people,” Rosenow says. With immigrant labor, “I’m pretty sure if I wanted to double employment, I could get it done within a week.”

To some economists, however, dependence on imported workers is approaching unhealthy levels in some places, stifling productivity growth and helping businesses delay the search for more sustainable solutions to labor shortages.

Those solutions could include bigger investments in automation, or more radical restructurings such as business closures, which are painful but may be necessary long-term, these economists say.

“Once industry is organised in a certain way and the structure encourages employers to recruit migrants, it can be very hard to turn back,” said Martin Ruhs , a professor of migration studies in Florence, Italy. “In some cases, policymakers should ask, does it make sense?” said Ruhs, who is also a former member of the U.K. Migration Advisory Committee, which advises the British government on migration policy.

The debate is likely to heat up further as Western societies teeter closer to a demographic abyss . For the first time since World War II, the working-age population is shrinking across advanced economies. The European Union’s working-age population will shrink by one-fifth through 2050, according to a recent report by German insurer Allianz .

There are ways to offset that trend, such as encouraging older workers to delay retirement. But importing foreign labour is often the easiest option, given the supply of available workers in places such as Latin America or Africa.

Immigration also provides a rush of economic growth as migrants boost populations and spend money, even when it elicits blowback from conservative groups, as it has in the U.S. and Europe.

Immigration is now running two to three times above pre pandemic levels across major destination countries including Canada, Germany and the U.K. In the U.S., 3.3 million more migrants arrived than left last year, compared with a 2010s average of around 900,000.

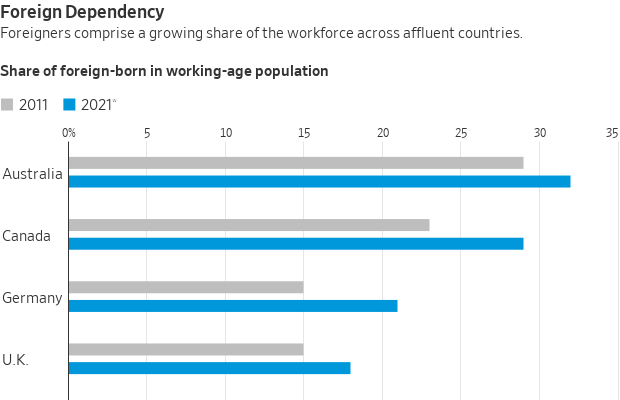

Three-quarters of farmworkers and 30% of construction and mining workers in the U.S. today are migrants. Overall, immigrants made up 18% of the U.S. workforce in 2021, compared with 16% a decade earlier, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, a Paris-based club of mostly rich countries.

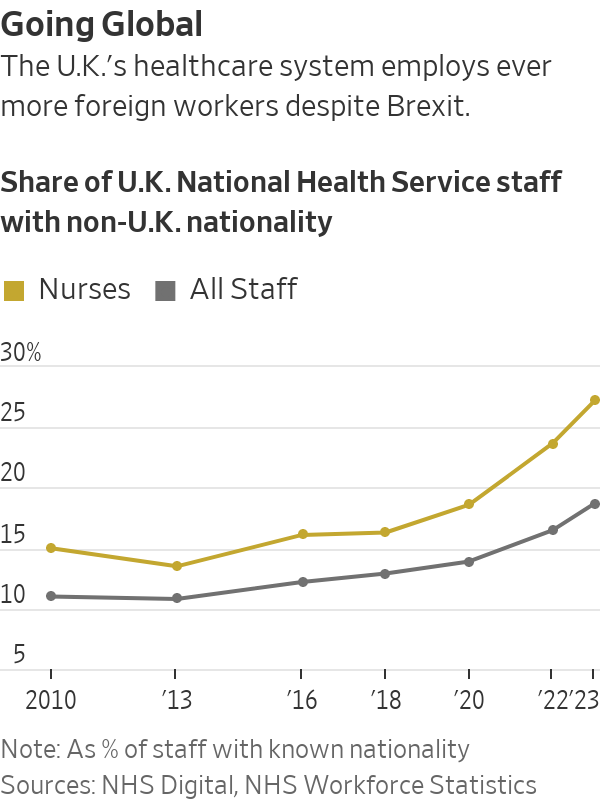

Despite promising for decades to curb immigration, the U.K. has seen a surge since its 2020 exit from the EU, as businesses scramble for employees. More than 27% of the National Health Service’s nurses are from abroad today, up from around 14% in 2013. In Germany, roughly 80% of slaughterhouse workers are migrants, unions estimate.

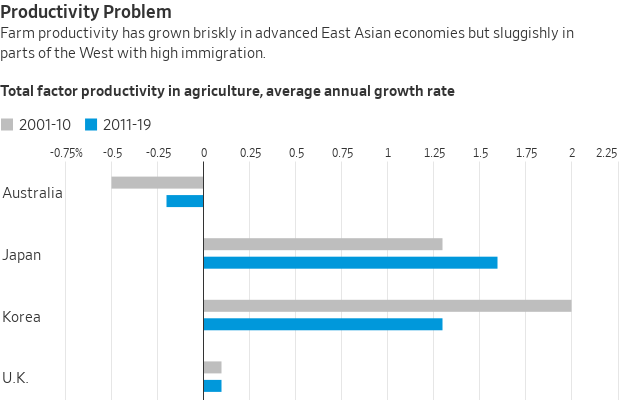

Increased reliance on low-skilled imported labor can lead to weaker productivity growth, which ultimately determines how fast economies can expand, some economic research suggests.

A 2022 study in Denmark found that firms with easy access to migrant workers invested less in robots. Research in Australia and Canada suggests that migrants could keep weak firms alive, weighing on overall productivity.

Labour productivity growth has been sluggish across advanced economies in recent years. In the U.S. and U.K. farming sectors, productivity has flatlined for a decade or longer. In Japan and Korea, which have more restrictive immigration policies, it increased by around 1.5% a year, OECD data show.

Finding the right balance between allowing some migration, which can help restore dynamism in aging countries, and avoiding over dependence is hard. In many industries, there is no obvious alternative to foreign workers.

Going cold turkey would send prices for products made from migrant labour higher. It would also leave many people in poorer countries with fewer options to pursue better lives.

Anna Boucher , a global migration expert at the University of Sydney, says that some low-skilled migration is probably necessary in the short term due to skills shortages. Without it, some childcare services in Australia would shut down and vegetables would die in the fields.

Economic research suggests that an influx of high-skilled migrants, such as scientists and engineers, can actually lift firms’ productivity and boost local workers’ wages and employment opportunities.

Economists are more divided when it comes to lower-skilled migrants. Such workers are also more easily replaced, including in industries that seem unlikely candidates for automation.

In the Czech Republic, some farmers are using artificial-intelligence-driven robots to monitor and harvest strawberries. Israeli startup Tevel Aerobotics Technologies has developed fruit-picking drones. Fieldwork Robotics, a U.K. company, recently started selling raspberry-picking robots, which stand 6 feet tall with four plastic arms.

Yet for governments, pursuing reforms that boost productivity and allow weaker firms to die is a lot harder than increasing immigration, said Dan Andrews , a productivity expert at the OECD.

“Some countries may have taken the easy way out,” he said.

Hoping to accelerate automation in agriculture, the U.K. government is pouring money into farm technology. It is also considering abolishing rules that allow companies to pay migrant workers 20% less than the going rate for jobs, prompting protests from farmers’ lobby groups. They say farmers adopt technology quickly if it is available, but that robots are no good at picking fruit and vegetables.

“The technology that we are aiming for is five years away…we were saying that five years ago,” said Martin Emmett , a farmer and official at the National Farmers’ Union, a trade group.

In Malaysia, the government last year announced a freeze on hiring of new foreign workers. Government ministers say that over dependence on cheap foreign labour has created a detrimental cycle that allows companies to resist innovation. Local companies say they need more time to invest in automation and upgrade workers’ skills.

Some industries, including manufacturing and plantations, have since been allowed to hire foreigners following appeals, but the broader freeze on foreign workers remains in place with no end date.

In Canada, economists say the government has cast aside a carefully managed immigration system that gave priority to highly skilled workers, and ramped up significantly the intake of foreign students and other low-skilled temporary workers. By flooding the market with cheap labor, Ottawa may be propping up uncompetitive businesses and ultimately damaging productivity, according to a December report co-written by former Canadian central-bank governor David Dodge .

Economic output per capita is lower than it was in 2018 following years of record immigration, notes Mikal Skuterud , an economist at Waterloo University in Ontario. Canada has been bringing in so many low-skilled workers that it lowers the country’s productivity overall, he says.

The debates are also intensifying in Germany, where businesses including butcher shops in the foothills of the Black Forest are becoming more reliant on imported labour.

Young people don’t want to train as butchers anymore, local businesses say, because it is unglamorous work, with low pay. Labour shortages are one reason why the number of butcher shops has roughly halved over the past two decades.

Three years ago, Handirk von Ungern-Sternberg , an official at the local chamber of handicrafts, started a pilot project to recruit butchers’ apprentices in India, taking advantage of a change in German law that made it easier to hire low-skilled workers from outside the EU. The first batch of 13 young Indians arrived in September 2022.

Now, demand is exploding. Von Ungern-Sternberg plans to bring in roughly 140 Indian workers this year. That number could triple in future, he says.

From auto mechanics to construction, local businesses are clamoring for his young Indian recruits. Chambers of handicrafts across Germany, from the Alps to the North Sea, are seeking his help in starting similar projects.

“We ask ourselves, where’s the limit? Are we a job company? We don’t know where the ceiling is,” von Ungern-Sternberg said.

The program also benefits consumers by helping keep butchers’ costs low. Across the border in Switzerland, where Indian workers aren’t available, meat costs nearly four times as much.

However, Swiss business owners have also been experimenting with new technologies, including sausage vending machines known as Wurstautomaten, which could reduce the need for small-scale butcher’s shops and ultimately help bring prices down.

Meanwhile, opposition to immigration is rising in Germany, which suggests the butchers’ reliance on imported labor might not be sustainable. Support for the anti-immigrant Alternative for Germany party recently hit an all-time high of 23%. Polls suggest it could emerge as the strongest political force in several German state elections later this year.

In Wisconsin, Rosenow, the dairy farmer, says he’s skeptical of the automated milking machines that he says are advertised in farm magazines. Some neighbours experimented with robots but went back to human labor because the robots constantly needed repairs, he says.

Robots would also cost twice as much as immigrant workers and be costly to maintain, Rosenow says. With immigrants, “labor is no constraint.”

Onan Whitcomb , a dairy farmer in Vermont, disagrees. He says that when he wanted to increase production he decided not to hire immigrant workers. Instead, he spent $800,000 on four Dutch-made milking robots.

Milk production per cow has grown by 30% and the incidence of mastitis, an inflammatory disease, has declined by 80%, he says, meaning less spent on antibiotics. Whitcomb says he was able to cut 2.5 jobs, and the investment paid for itself in seven years.

“We were milking 300 cows and we went to 240, and we still made more” milk, Whitcomb said. “That’s hard to beat.”

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

What a quarter-million dollars gets you in the western capital.

Alexandre de Betak and his wife are focusing on their most personal project yet.

CIOs can take steps now to reduce risks associated with today’s IT landscape

As tech leaders race to bring Windows systems back online after Friday’s software update by cybersecurity company CrowdStrike crashed around 8.5 million machines worldwide, experts share with CIO Journal their takeaways for preparing for the next major information technology outage.

IT leaders should hold vendors deeply integrated within IT systems, such as CrowdStrike , to a “very high standard” of development, release quality and assurance, said Neil MacDonald , a Gartner vice president.

“Any security vendor has a responsibility to do extensive regression testing on all versions of Windows before an update is rolled out,” he said.

That involves asking existing vendors to explain how they write software, what testing they do and whether customers may choose how quickly to roll out an update.

“Incidents like this remind all of us in the CIO community of the importance of ensuring availability, reliability and security by prioritizing guardrails such as deployment and testing procedures and practices,” said Amy Farrow, chief information officer of IT automation and security company Infoblox.

While automatically accepting software updates has become the norm—and a recommended security practice—the CrowdStrike outage is a reminder to take a pause, some CIOs said.

“We still should be doing the full testing of packages and upgrades and new features,” said Paul Davis, a field chief information security officer at software development platform maker JFrog . undefined undefined Though it’s not feasible to test every update, especially for as many as hundreds of software vendors, Davis said he makes it a priority to test software patches according to their potential severity and size.

Automation, and maybe even artificial intelligence-based IT tools, can help.

“Humans are not very good at catching errors in thousands of lines of code,” said Jack Hidary, chief executive of AI and quantum company SandboxAQ. “We need AI trained to look for the interdependence of new software updates with the existing stack of software.”

An incident rendering Windows computers unusable is similar to a natural disaster with systems knocked offline, said Gartner’s MacDonald. That’s why businesses should consider natural disaster recovery plans for maintaining the resiliency of their operations.

One way to do that is to set up a “clean room,” or an environment isolated from other systems, to use to bring critical systems back online, according to Chirag Mehta, a cybersecurity analyst at Constellation Research.

Businesses should also hold tabletop exercises to simulate risk scenarios, including IT outages and potential cyber threats, Mehta said.

Companies that back up data regularly were likely less impacted by the CrowdStrike outage, according to Victor Zyamzin, chief business officer of security company Qrator Labs. “Another suggestion for companies, and we’ve been saying that again and again for decades, is that you should have some backup procedure applied, running and regularly tested,” he said.

For any vendor with a significant impact on company operations , MacDonald said companies can review their contracts and look for clauses indicating the vendors must provide reliable and stable software.

“That’s where you may have an advantage to say, if an update causes an outage, is there a clause in the contract that would cover that?” he said.

If it doesn’t, tech leaders can aim to negotiate a discount serving as a form of compensation at renewal time, MacDonald added.

The outage also highlights the importance of insurance in providing companies with bottom-line protection against cyber risks, said Peter Halprin, a partner with law firm Haynes Boone focused on cyber insurance.

This coverage can include protection against business income losses, such as those associated with an outage, whether caused by the insured company or a service provider, Halprin said.

The CrowdStrike update affected only devices running Microsoft Windows-based systems , prompting fresh questions over whether enterprises should rely on Windows computers.

CrowdStrike runs on Windows devices through access to the kernel, the part of an operating system containing a computer’s core functions. That’s not the same for Apple ’s Mac operating system and Linux, which don’t allow the same level of access, said Mehta.

Some businesses have converted to Chromebooks , simple laptops developed by Alphabet -owned Google that run on the Chrome operating system . “Not all of them require deeper access to things,” Mehta said. “What are you doing on your laptop that actually requires Windows?”