The $65 Million Perk for CEOs: Personal Use of the Corporate Jet Has Soared

Company spending on the benefit has climbed 50% since before the pandemic

Company spending on the benefit has climbed 50% since before the pandemic

One of the flashiest executive perks has roared back since the onset of the pandemic: free personal travel on the company jet.

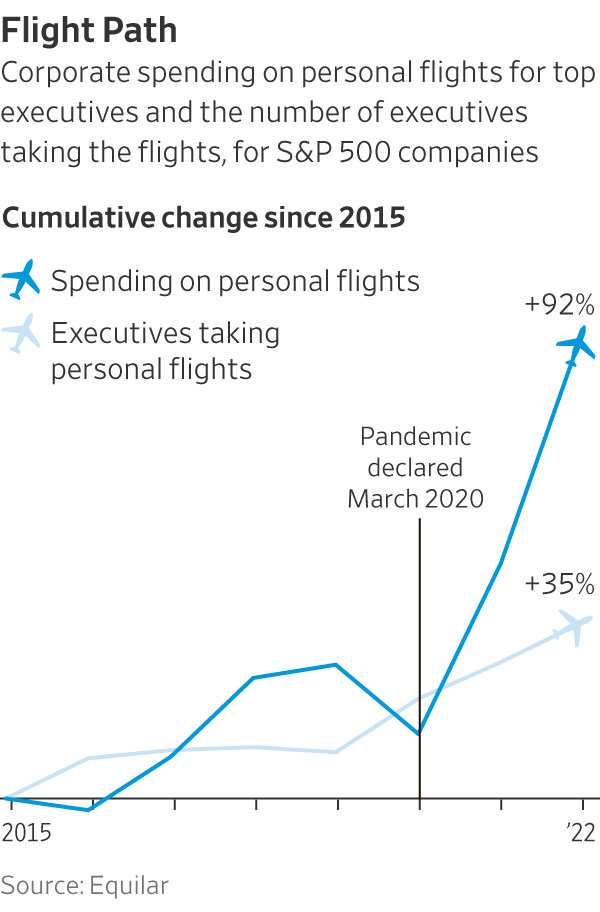

Companies in the S&P 500 spent $65 million for executives to use corporate jets for personal travel in 2022, up about 50% from prepandemic levels three years earlier, a Wall Street Journal analysis found. Early signs suggest the trend continued last year.

Overall, the number of big companies providing the perk rose about 14% since 2019, to 216 in 2022, figures from executive-data firmEquilar show. The number of executives receiving free flights grew nearly 25%, to 427.

Most companies report executive pay and perks in the spring.

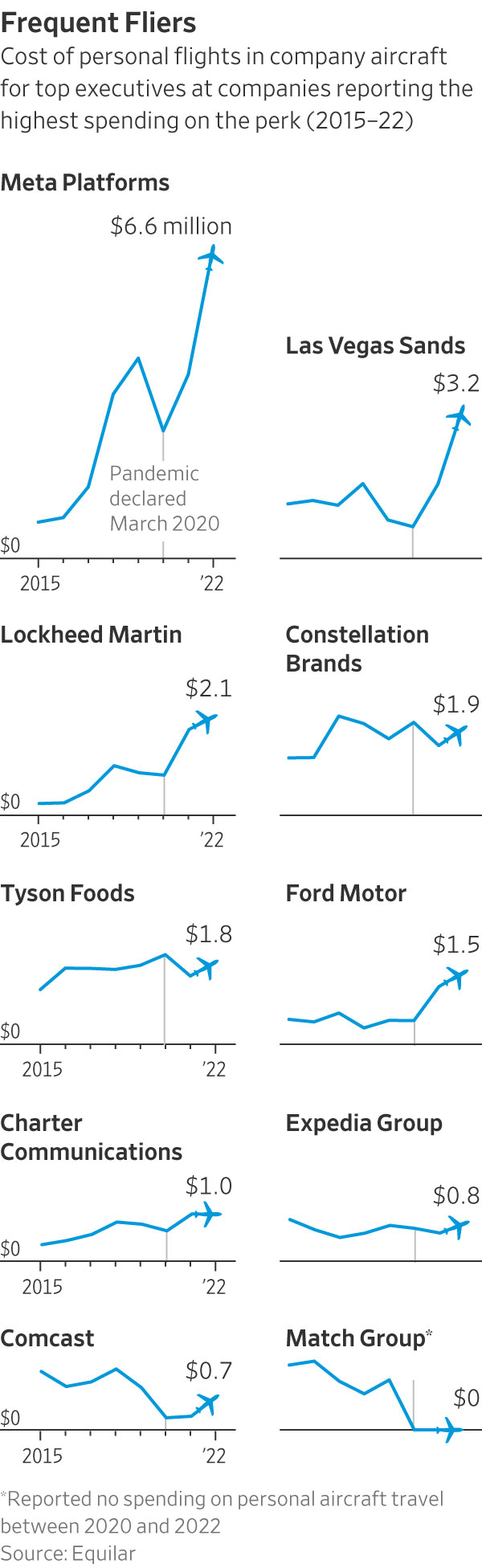

Meta Platforms spent $6.6 million in 2022 on personal flights for Chief Executive Mark Zuckerberg and his then-lieutenant, Sheryl Sandberg—up about 55% from 2019, the Journal found. Casino company Las Vegas Sands spent $3.2 million on flights for four executives, more than double its annual expense in any year since 2015. Exelon, which owns Chicago’s Commonwealth Edison utility, more than tripled its spending on the perk since 2019.

Company jets have long symbolised corporate success and, to critics, excess. Companies typically say flying corporate is safer, healthier and more efficient. Some companies—including Cardinal Health, Raymond James Financial and Hormel Foods—added or expanded the perk in 2020 or 2021, citing pandemic health and safety concerns. Most spending growth came at companies already paying for personal flights in 2019.

Palo Alto Networks began subsidising personal flights for CEO Nikesh Arora in the year ended July 2022, spending about $650,000. Thattotal rose to $1.8 million in its most recent fiscal year, plus a further $286,000 to cover his tax bill for the perk, the cybersecurity company said in an October securities filing.

The company said in filings that its board requires Arora to fly corporate in response to a security consultant’s report. “There was a bona fide, business-related security concern for Mr. Arora and credible threat actors existed with both the willingness and resources necessary for conducting an attack on Mr. Arora,” it said.

Companies report spending on flights they can’t classify as business-related, including trips to board meetings for other companies or commuting from distant residences. Some give executives a fixed personal-flight allowance in hours or dollars, and require reimbursement beyond that.

The sums have little financial impact on most giant corporations, even when annual flight bills exceed a million dollars. Critics say the free flights indicate directors too eager to please top executives.

“The vast majority of S&P 500 companies do not offer this perk,” said Rosanna Landis Weaver, an executive-pay analyst at As You Sow, a nonprofit shareholder-advocacy group that has produced annual lists of CEOs it considers overpaid.

The Journal’s analysis reflects what companies disclose in securities filings, typically in footnotes to annual proxy statements. Federal rules generally require companies to itemise the perk for each top executive if it costs the company $25,000 or more in a year.

PepsiCo spent $776,000 on personal flights for five executives in 2022, double what it paid for the perk in 2019. Two-thirds of the spending subsidised flights by CEO Ramon Laguarta, who is required to use company aircraft for personal flights for safety and efficiency reasons. In an interview last spring, Laguarta said he sometimes ended business trips to Europe by flying to visit his mother in his native Barcelona. She died later in the year, in her 90s.

A PepsiCo spokesman said the company jet allows executives to reach remote facilities.

Personal jet use can draw investor and regulatory scrutiny. It contributed to the ouster of Credit Suisse’s chairman in 2022.

In June, tool maker Stanley Black & Decker settled Securities and Exchange Commission charges that it failed to disclose $1.3 million in perks for four executives and a director, mostly their use of company aircraft, from 2017 through 2020. In 2020, Hilton Worldwide Holdings settled SEC charges that it didn’t disclose $1.7 million in perks over four years, in part by underreporting costs for CEO Christopher Nassetta’s personal flights by 87%in two of those years. Hilton paid a $600,000 penalty.

Both companies settled without admitting or denying wrongdoing.

Stanley Black & Decker said it raised the errors with the SEC and settled without a fine. In 2022, Stanley Black & Decker reported spending nearly $143,500 on personal flights for former CEO James Loree and his successor, Donald Allan Jr., primarily to fly to outside board meetings or from second homes to work.

Hilton cited higher fuel prices in reporting about $500,000 in flights for Nassetta in 2022.

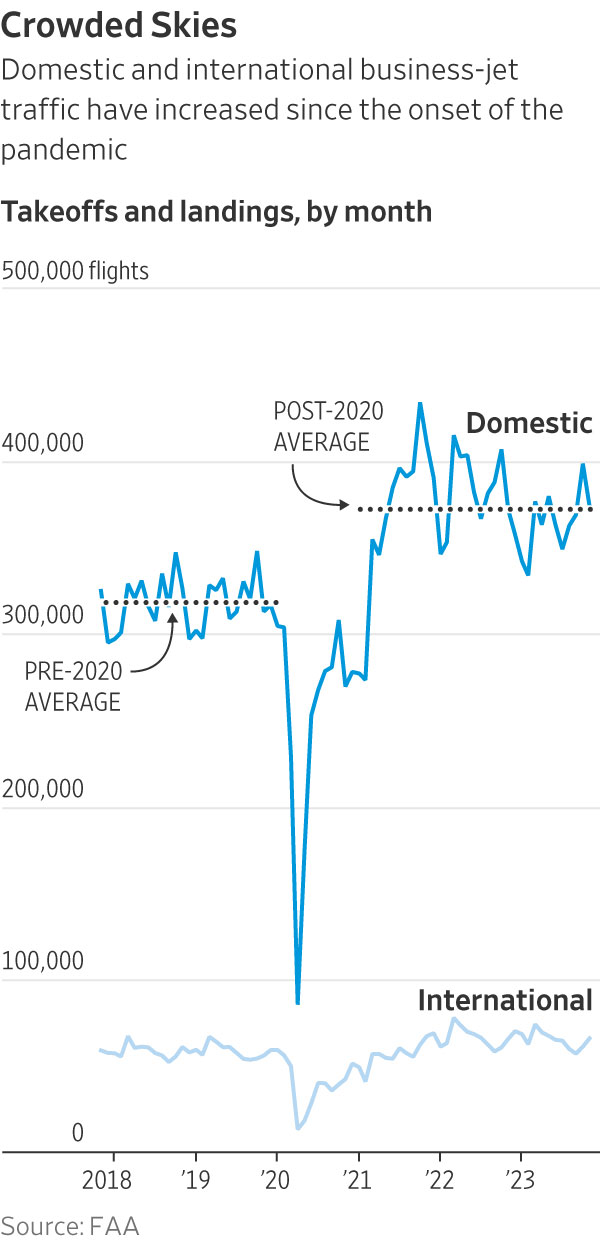

Spending on executives’ personal travel outpaced overall growth in business-jet traffic. Takeoffs and landings are up by about 19% since 2019, after dropping sharply in 2020, Federal Aviation Administration data show. Corporate spending on the perk rose 52%, the Journal found.

Higher fuel costs in 2022 contributed to the increase in spending, and there is little indication of a slowdown last year. Of the 15 S&P 500 companies that have reported spending on the perk in fiscal years ended in the second half of 2023, 10 said they increased spending, including three that didn’t report the perk a year earlier, securities filings show.

Sixteen companies that started paying for personal flights during the pandemic have since stopped. An additional 31 continued spending into 2022, with a median of $124,000. Accenture, Palo Alto Networks and concert promoter Live Nation Entertainment reported spending more than $500,000 apiece.

In 2020, Julie Sweet’s first full year as CEO, Accenture capped annual spending for her personal flights at $200,000, then doubled it the next year. Accenture raised the cap to $600,000 in its year that ended Aug. 31, when it spent about $575,000 on Sweet’s personal flights, the company said in a December securities filing.

In its filings, Accenture said it encourages Sweet to use company aircraft for personal travel, citing a security study the company commissioned.

Companies that provided the perk already in 2019 accounted for most of the recent growth in spending, the Journal found.

Meta, for example, spent nearly $11 million on Zuckerberg and Sandberg’s personal flights from 2015 through 2019, and a further $13.3 million over the next three years. Zuckerberg’s company-paid travel included trips on an aircraft he owns, which Meta charters for business, paying $523,000 in 2022. The Facebook owner stopped paying for Sandberg’s personal flights when she stepped down as a company employee in September 2022. She remains on Meta’s board.

Spokesmen for Meta and Sandberg declined to comment beyond Meta’s securities disclosures.

CEOs incurred most of the personal flight spending, making up half the executives receiving the perk in 2022 and two-thirds of the overall cost, Equilar’s data show.

At some companies, other executives are making up a bigger share of the cost. Four Norfolk Southern executive vice presidents accounted for just over half its roughly $370,000 in spending on personal flights in 2022, securities filings show. CEO Alan Shaw accounted for the rest. By contrast, the railroad reported subsidizing flights only for then-CEO James Squires in the five years through 2020.

Shaw may take as many as 60 hours of personal flights on company aircraft before reimbursing Norfolk Southern, the company said in its filings. Personal use of company aircraft by executives other than the CEO was infrequent, it added. Norfolk Southern didn’t respond to requests for comment.

—Jennifer Maloney contributed to this article.

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

What a quarter-million dollars gets you in the western capital.

Alexandre de Betak and his wife are focusing on their most personal project yet.

CIOs can take steps now to reduce risks associated with today’s IT landscape

As tech leaders race to bring Windows systems back online after Friday’s software update by cybersecurity company CrowdStrike crashed around 8.5 million machines worldwide, experts share with CIO Journal their takeaways for preparing for the next major information technology outage.

IT leaders should hold vendors deeply integrated within IT systems, such as CrowdStrike , to a “very high standard” of development, release quality and assurance, said Neil MacDonald , a Gartner vice president.

“Any security vendor has a responsibility to do extensive regression testing on all versions of Windows before an update is rolled out,” he said.

That involves asking existing vendors to explain how they write software, what testing they do and whether customers may choose how quickly to roll out an update.

“Incidents like this remind all of us in the CIO community of the importance of ensuring availability, reliability and security by prioritizing guardrails such as deployment and testing procedures and practices,” said Amy Farrow, chief information officer of IT automation and security company Infoblox.

While automatically accepting software updates has become the norm—and a recommended security practice—the CrowdStrike outage is a reminder to take a pause, some CIOs said.

“We still should be doing the full testing of packages and upgrades and new features,” said Paul Davis, a field chief information security officer at software development platform maker JFrog . undefined undefined Though it’s not feasible to test every update, especially for as many as hundreds of software vendors, Davis said he makes it a priority to test software patches according to their potential severity and size.

Automation, and maybe even artificial intelligence-based IT tools, can help.

“Humans are not very good at catching errors in thousands of lines of code,” said Jack Hidary, chief executive of AI and quantum company SandboxAQ. “We need AI trained to look for the interdependence of new software updates with the existing stack of software.”

An incident rendering Windows computers unusable is similar to a natural disaster with systems knocked offline, said Gartner’s MacDonald. That’s why businesses should consider natural disaster recovery plans for maintaining the resiliency of their operations.

One way to do that is to set up a “clean room,” or an environment isolated from other systems, to use to bring critical systems back online, according to Chirag Mehta, a cybersecurity analyst at Constellation Research.

Businesses should also hold tabletop exercises to simulate risk scenarios, including IT outages and potential cyber threats, Mehta said.

Companies that back up data regularly were likely less impacted by the CrowdStrike outage, according to Victor Zyamzin, chief business officer of security company Qrator Labs. “Another suggestion for companies, and we’ve been saying that again and again for decades, is that you should have some backup procedure applied, running and regularly tested,” he said.

For any vendor with a significant impact on company operations , MacDonald said companies can review their contracts and look for clauses indicating the vendors must provide reliable and stable software.

“That’s where you may have an advantage to say, if an update causes an outage, is there a clause in the contract that would cover that?” he said.

If it doesn’t, tech leaders can aim to negotiate a discount serving as a form of compensation at renewal time, MacDonald added.

The outage also highlights the importance of insurance in providing companies with bottom-line protection against cyber risks, said Peter Halprin, a partner with law firm Haynes Boone focused on cyber insurance.

This coverage can include protection against business income losses, such as those associated with an outage, whether caused by the insured company or a service provider, Halprin said.

The CrowdStrike update affected only devices running Microsoft Windows-based systems , prompting fresh questions over whether enterprises should rely on Windows computers.

CrowdStrike runs on Windows devices through access to the kernel, the part of an operating system containing a computer’s core functions. That’s not the same for Apple ’s Mac operating system and Linux, which don’t allow the same level of access, said Mehta.

Some businesses have converted to Chromebooks , simple laptops developed by Alphabet -owned Google that run on the Chrome operating system . “Not all of them require deeper access to things,” Mehta said. “What are you doing on your laptop that actually requires Windows?”