The Improbably Strong Economy

A lot had to go right for the U.S. to avoid a recession. So far, it has.

A lot had to go right for the U.S. to avoid a recession. So far, it has.

The economy is still generating jobs. A year ago, a lot of economists and Federal Reserve policy makers thought that it would be shedding them by now.

On Friday, the Labor Department reported that the U.S. added a seasonally 150,000 jobs in October from the previous month, versus September’s gain of 297,000 jobs. Some of that step down was due to auto workers’ strikes, which have since been resolved but temporarily caused workers to not draw paychecks.

Average hourly earnings rose 0.2% from a month earlier, putting them 4.1% higher than a year earlier. That was the smallest year-over-year gain since June 2021, though unlike then wages are now outpacing inflation.

One takeaway is that the job market is moderating, but not buckling—a message reinforced by a variety of other data, including low levels of weekly unemployment claims and layoffs. Another is that the Federal Reserve is probably through with tightening: Futures markets on Friday morning indicated that the chance of the central bank raising its target range on overnight rates at its December meeting was below 10%. The yield on the 10-year Treasury note, which briefly hit 5% less than two weeks ago, continued to retreat Friday, falling to 4.53% midmorning.

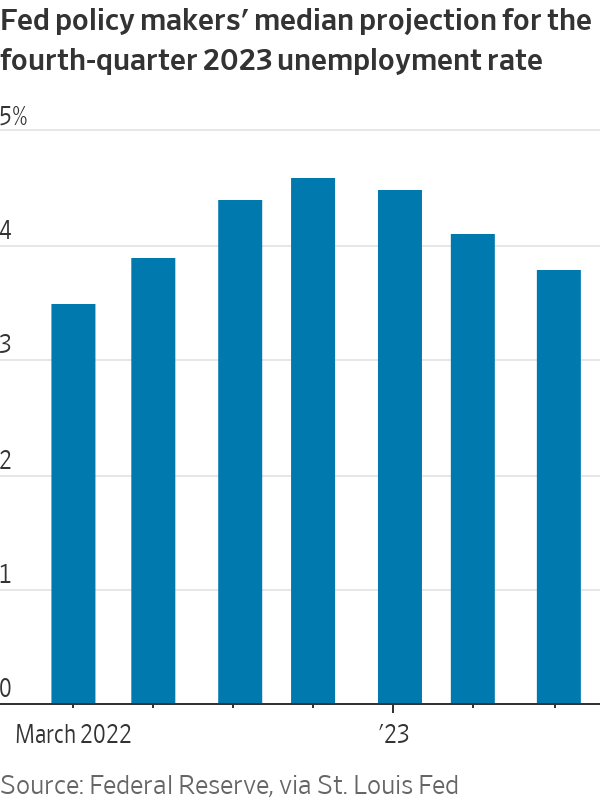

This wasn’t the sort of job market the Fed expected. When policy makers offered projections last December, they forecast that the unemployment rate would average 4.6% in this year’s fourth quarter, versus the 3.7% rate (since revised to 3.6%) they had seen in the November 2022 job report. That was tantamount to a recession forecast, though they didn’t put it that way, since such a large increase in the unemployment rate would count as a strong signal the U.S. is in a downturn. Friday’s report showed the October unemployment rate at 3.9%.

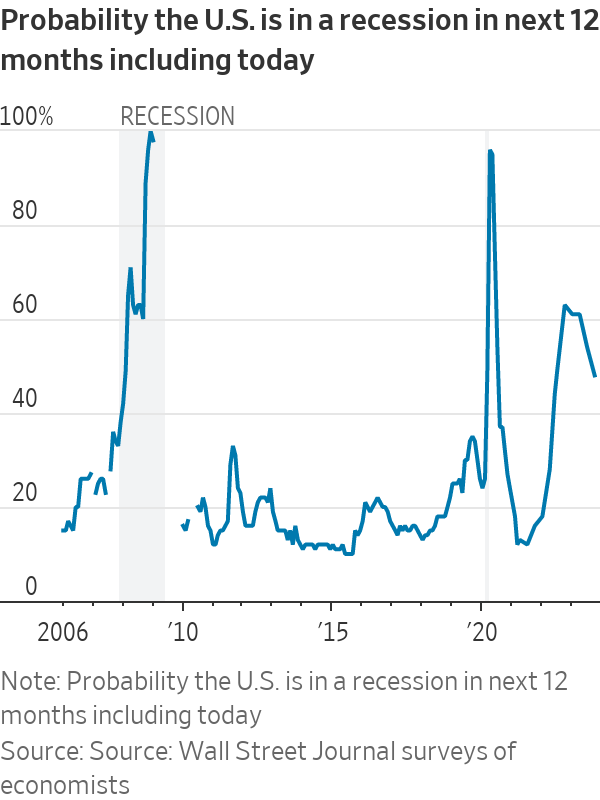

Economists got it wrong, too. In October of last year, forecasters polled by The Wall Street Journal estimated the unemployment rate at the end of 2023 to be at 4.7%, on average. They also put the chances of a recession within the next 12 months at 63%. By last month, they dropped the recession chance to 48%. Available data show that, as a group, economists have never forecast a recession before it has actually started. Now it looks as if the one time they did forecast one, they were either wrong or early.

It is easy to make fun of other people’s past forecasts, but considering the hurdles the economy has had to clear, it really is striking that it has done so well. A year ago there was some hope that the continued recovery in the service sector, and service-sector jobs, might help take up the slack as the goods sector adjusted to slowing demand. But there was also the concern that the service sector could run out of steam before the goods sector found its footing.

Another worry: That the excess savings that Americans had built up after the pandemic struck would run out, and that would cut into their ability to spend. But recent revisions to the available data suggest there was more money left in the tank than thought.

To these, add that inflation has cooled despite the addition of 2.4 million jobs so far this year, and gross domestic product is expanding much faster than economists expected. Plus, at least so far this year, the economy has made it through a regional bank crisis, a sharp increase in both short- and long-term borrowing costs, and the resumption of student-debt payments.

The jury is out on what happens next. The cooling in the job market could turn into a lurch lower, for example, as the full effect of the Fed’s past rate increases begins to take hold. Inflation, which is still too high, could accelerate, prompting the central bank to further tighten the screws.

But the chances of the economy avoiding a recession seem stronger now than they did even a few months ago. A lot of that would be down to luck, but it would nonetheless be something worth celebrating.

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

What a quarter-million dollars gets you in the western capital.

Alexandre de Betak and his wife are focusing on their most personal project yet.

CIOs can take steps now to reduce risks associated with today’s IT landscape

As tech leaders race to bring Windows systems back online after Friday’s software update by cybersecurity company CrowdStrike crashed around 8.5 million machines worldwide, experts share with CIO Journal their takeaways for preparing for the next major information technology outage.

IT leaders should hold vendors deeply integrated within IT systems, such as CrowdStrike , to a “very high standard” of development, release quality and assurance, said Neil MacDonald , a Gartner vice president.

“Any security vendor has a responsibility to do extensive regression testing on all versions of Windows before an update is rolled out,” he said.

That involves asking existing vendors to explain how they write software, what testing they do and whether customers may choose how quickly to roll out an update.

“Incidents like this remind all of us in the CIO community of the importance of ensuring availability, reliability and security by prioritizing guardrails such as deployment and testing procedures and practices,” said Amy Farrow, chief information officer of IT automation and security company Infoblox.

While automatically accepting software updates has become the norm—and a recommended security practice—the CrowdStrike outage is a reminder to take a pause, some CIOs said.

“We still should be doing the full testing of packages and upgrades and new features,” said Paul Davis, a field chief information security officer at software development platform maker JFrog . undefined undefined Though it’s not feasible to test every update, especially for as many as hundreds of software vendors, Davis said he makes it a priority to test software patches according to their potential severity and size.

Automation, and maybe even artificial intelligence-based IT tools, can help.

“Humans are not very good at catching errors in thousands of lines of code,” said Jack Hidary, chief executive of AI and quantum company SandboxAQ. “We need AI trained to look for the interdependence of new software updates with the existing stack of software.”

An incident rendering Windows computers unusable is similar to a natural disaster with systems knocked offline, said Gartner’s MacDonald. That’s why businesses should consider natural disaster recovery plans for maintaining the resiliency of their operations.

One way to do that is to set up a “clean room,” or an environment isolated from other systems, to use to bring critical systems back online, according to Chirag Mehta, a cybersecurity analyst at Constellation Research.

Businesses should also hold tabletop exercises to simulate risk scenarios, including IT outages and potential cyber threats, Mehta said.

Companies that back up data regularly were likely less impacted by the CrowdStrike outage, according to Victor Zyamzin, chief business officer of security company Qrator Labs. “Another suggestion for companies, and we’ve been saying that again and again for decades, is that you should have some backup procedure applied, running and regularly tested,” he said.

For any vendor with a significant impact on company operations , MacDonald said companies can review their contracts and look for clauses indicating the vendors must provide reliable and stable software.

“That’s where you may have an advantage to say, if an update causes an outage, is there a clause in the contract that would cover that?” he said.

If it doesn’t, tech leaders can aim to negotiate a discount serving as a form of compensation at renewal time, MacDonald added.

The outage also highlights the importance of insurance in providing companies with bottom-line protection against cyber risks, said Peter Halprin, a partner with law firm Haynes Boone focused on cyber insurance.

This coverage can include protection against business income losses, such as those associated with an outage, whether caused by the insured company or a service provider, Halprin said.

The CrowdStrike update affected only devices running Microsoft Windows-based systems , prompting fresh questions over whether enterprises should rely on Windows computers.

CrowdStrike runs on Windows devices through access to the kernel, the part of an operating system containing a computer’s core functions. That’s not the same for Apple ’s Mac operating system and Linux, which don’t allow the same level of access, said Mehta.

Some businesses have converted to Chromebooks , simple laptops developed by Alphabet -owned Google that run on the Chrome operating system . “Not all of them require deeper access to things,” Mehta said. “What are you doing on your laptop that actually requires Windows?”