Well Into Adulthood and Still Getting Money From Their Parents

Nearly 60% of parents provide financial help to their adult kids, a new study finds

Nearly 60% of parents provide financial help to their adult kids, a new study finds

Parents have always supported their children into adulthood, from funding weddings to buying a home. Now the financial umbilical cord extends much later into adulthood.

About 59% of parents said they helped their young adult children financially in the past year, according to a report released Thursday by the Pew Research Center that focused on adults under age 35. (This question hadn’t been asked in prior surveys.) More young adults are also living with their parents. Among adults under age 25, 57% live with their parents, up from 53% in 1993.

Parental support is continuing later in life because younger people now take longer to reach many adult milestones—and getting there is more expensive than it has been for past generations, economists and researchers said. There is also a larger wealth gap between older Americans and younger ones, giving some parents more means and reason to help. In short, adulthood no longer means moving off the parental payroll.

“That transition has gotten later and later, for a lot of different reasons. Now it’s age 25, 30, 35, 40,” said Sarah Behr, founder of Simplify Financial Planning in San Francisco.

Kami Loukipoudis, a 39-year-old director of design, and husband Adam Stojanik, a 39-year-old high-school teacher, knew they would need parental assistance to buy in New York’s expensive home market.

“We could pay a mortgage, but that down payment was the absolute crusher,” Stojanik said. “The idea of trying to save up on our own—as long as we were paying rents in NY, would’ve taken 300 years.”

Loukipoudis’s mother gave them the money for a 10% down payment on a two-bedroom apartment in the New York borough of Queens.

Adult children aren’t necessarily getting larger checks from their parents, but they are staying on the parental payroll for longer than previous generations, according to Marla Ripoll, professor of economics at the University of Pittsburgh who studied the trend by analysing payments from parents to adult children over a 20-year span.

Ripoll found that 14% of adult children receive a transfer of money from their parents at least once in any given year, and roughly half get financial help at some point within that period. Those rates have been stable for years. What has changed is that the transfers now continue for much longer, she found. This longer-term help might be a drag on social mobility, as it becomes even harder for young people from lower-income families to catch up, researchers said.

Of the young adult children who said they received financial help from a parent in the past year, most said they put it toward day-to-day household expenses, such as phone bills and subscriptions to streaming services like Netflix, according to the Pew survey.

The amount of money and the frequency of help varies by age; those on the older end of the 18-to-34 cohort are far likelier to say they are completely financially independent from their parents compared with younger adult children, as many in the latter group are completing their education. Nearly a third of young adult children between the ages of 30 and 34 say they still get parental help.

Heather McAfee, a 33-year-old physical therapist in Austin, Texas, said she lived at home between 2019 and 2021; otherwise she wouldn’t have been able to make progress paying down her student loans while rent prices in her area remained so high. The plan worked—she has since reduced her student-debt balance from $83,000 to $15,000.

“It helped tremendously,” she said. “I didn’t have to take out more loans to pay for apartment living or anything like that. That stress was gone.”

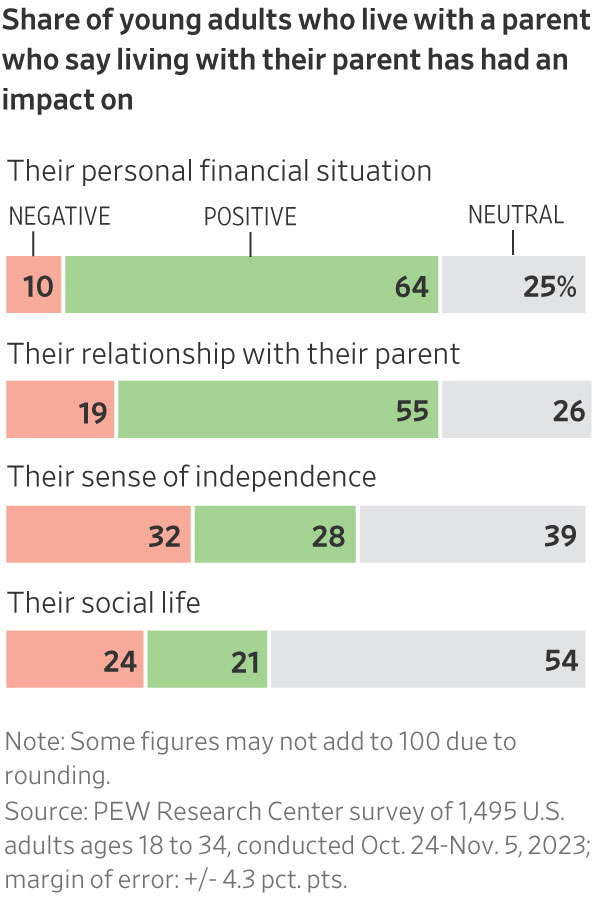

A little more than half of parents surveyed said that having their adult children home brought them closer together or improved their relationship, but nearly 20% said it dented their personal finances.

Financial advisers often find themselves in the tricky position of speaking to both ends of the equation: adult children who need assistance and the parents determined to help children well into middle age, within limits.

Whereas previous generations would step into a greater sense of financial independence in their early 20s, young adult children today are often unable to reach similar markers of such independence—living on their own or buying their first home, for example—without greater financial resources.

Families typically don’t set concrete rules around when financial help will happen and what the money is used for, which can result in surprises down the road, Behr said.

In one case, Behr’s clients received the down payment they needed to purchase a condo from a generous mother-in-law. Years later, that same mother-in-law told them she expected a payout once the couple sold the home.

Down-payment help from parents—a given for many first-time home buyers—is growing thanks to higher home prices and elevated mortgage rates.

About a fifth of first-time home buyers said they got help from a relative or friend when pulling together the money needed for a down payment, according to a 2023 survey of home buyers and sellers from the National Association of Realtors. And 38% of home buyers under age 30 received help with the down payment from their parents, according to a survey this spring by Redfin.

Wealthy families often go further than helping with the down payment. They become a true bank of mom and dad and write a mortgage. The Internal Revenue Service sets minimum levels of interest for such loans, which remain significantly cheaper than current mortgage rates.

Timothy Burke, chief executive at National Family Mortgage, which facilitates such loans, said parents are often frustrated on behalf of their house-hunting children. High interest rates and the cutthroat housing market are holding their children back from reaching a milestone the parents themselves were more easily able to access.

Mei Chao, a 41-year-old stay-at-home mom, and her husband, William Chao, a 44-year-old information-technology specialist, bought their first house as a couple in 2017. They relied on financial help from her husband’s two sisters and his mother to help them bridge a gap in their house-buying timeline. While they waited to sell William’s Manhattan condo, they used the money from the family to purchase the new house in Queens.

The structure of the agreements got tricky. After selling the condo in Manhattan, Mei and her husband were able to repay his sisters in full. But they didn’t have enough money left over from the sale to do the same for Mei’s mother-in-law. So they kept the mother-in-law’s name on the deed to the house—a concession Mei said they were both more than happy to make.

“Ultimately, it all worked out. I’m glad his mother pushed us,” Mei said. “Without her help, I could not say we would have this home.”

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

What a quarter-million dollars gets you in the western capital.

Alexandre de Betak and his wife are focusing on their most personal project yet.

CIOs can take steps now to reduce risks associated with today’s IT landscape

As tech leaders race to bring Windows systems back online after Friday’s software update by cybersecurity company CrowdStrike crashed around 8.5 million machines worldwide, experts share with CIO Journal their takeaways for preparing for the next major information technology outage.

IT leaders should hold vendors deeply integrated within IT systems, such as CrowdStrike , to a “very high standard” of development, release quality and assurance, said Neil MacDonald , a Gartner vice president.

“Any security vendor has a responsibility to do extensive regression testing on all versions of Windows before an update is rolled out,” he said.

That involves asking existing vendors to explain how they write software, what testing they do and whether customers may choose how quickly to roll out an update.

“Incidents like this remind all of us in the CIO community of the importance of ensuring availability, reliability and security by prioritizing guardrails such as deployment and testing procedures and practices,” said Amy Farrow, chief information officer of IT automation and security company Infoblox.

While automatically accepting software updates has become the norm—and a recommended security practice—the CrowdStrike outage is a reminder to take a pause, some CIOs said.

“We still should be doing the full testing of packages and upgrades and new features,” said Paul Davis, a field chief information security officer at software development platform maker JFrog . undefined undefined Though it’s not feasible to test every update, especially for as many as hundreds of software vendors, Davis said he makes it a priority to test software patches according to their potential severity and size.

Automation, and maybe even artificial intelligence-based IT tools, can help.

“Humans are not very good at catching errors in thousands of lines of code,” said Jack Hidary, chief executive of AI and quantum company SandboxAQ. “We need AI trained to look for the interdependence of new software updates with the existing stack of software.”

An incident rendering Windows computers unusable is similar to a natural disaster with systems knocked offline, said Gartner’s MacDonald. That’s why businesses should consider natural disaster recovery plans for maintaining the resiliency of their operations.

One way to do that is to set up a “clean room,” or an environment isolated from other systems, to use to bring critical systems back online, according to Chirag Mehta, a cybersecurity analyst at Constellation Research.

Businesses should also hold tabletop exercises to simulate risk scenarios, including IT outages and potential cyber threats, Mehta said.

Companies that back up data regularly were likely less impacted by the CrowdStrike outage, according to Victor Zyamzin, chief business officer of security company Qrator Labs. “Another suggestion for companies, and we’ve been saying that again and again for decades, is that you should have some backup procedure applied, running and regularly tested,” he said.

For any vendor with a significant impact on company operations , MacDonald said companies can review their contracts and look for clauses indicating the vendors must provide reliable and stable software.

“That’s where you may have an advantage to say, if an update causes an outage, is there a clause in the contract that would cover that?” he said.

If it doesn’t, tech leaders can aim to negotiate a discount serving as a form of compensation at renewal time, MacDonald added.

The outage also highlights the importance of insurance in providing companies with bottom-line protection against cyber risks, said Peter Halprin, a partner with law firm Haynes Boone focused on cyber insurance.

This coverage can include protection against business income losses, such as those associated with an outage, whether caused by the insured company or a service provider, Halprin said.

The CrowdStrike update affected only devices running Microsoft Windows-based systems , prompting fresh questions over whether enterprises should rely on Windows computers.

CrowdStrike runs on Windows devices through access to the kernel, the part of an operating system containing a computer’s core functions. That’s not the same for Apple ’s Mac operating system and Linux, which don’t allow the same level of access, said Mehta.

Some businesses have converted to Chromebooks , simple laptops developed by Alphabet -owned Google that run on the Chrome operating system . “Not all of them require deeper access to things,” Mehta said. “What are you doing on your laptop that actually requires Windows?”