Why Prices of the World’s Most Expensive Handbags Keep Rising

Designers are charging more for their most recognisable bags to maintain the appearance of exclusivity as the industry balloons

Designers are charging more for their most recognisable bags to maintain the appearance of exclusivity as the industry balloons

The price of a basic Hermès Birkin handbag has jumped $1,000. This first-world problem for fashionistas is a sign that luxury brands are playing harder to get with their most sought-after products.

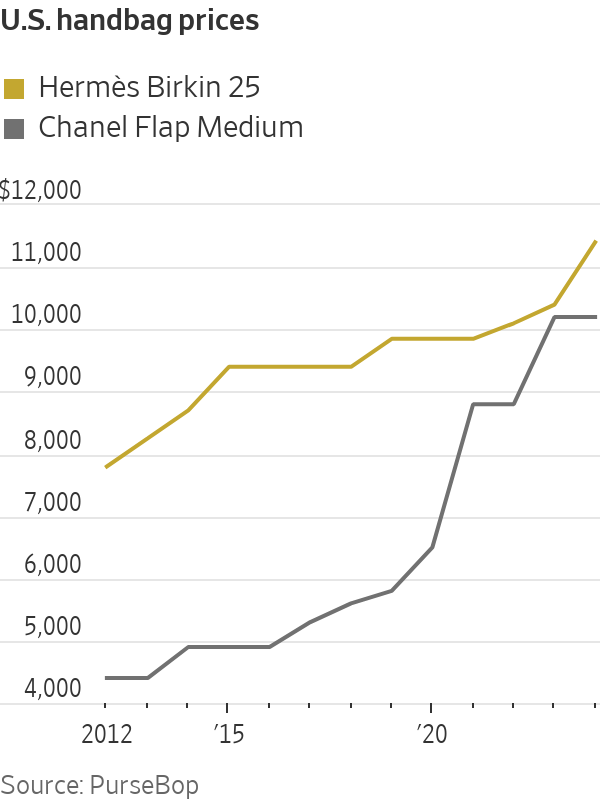

Hermès recently raised the cost of a basic Birkin 25-centimetre handbag in its U.S. stores by 10% to $11,400 before sales tax, according to data from luxury handbag forum PurseBop. Rarer Birkins made with exotic skins such as crocodile have jumped more than 20%. The Paris brand says it only increases prices to offset higher manufacturing costs, but this year’s increase is its largest in at least a decade.

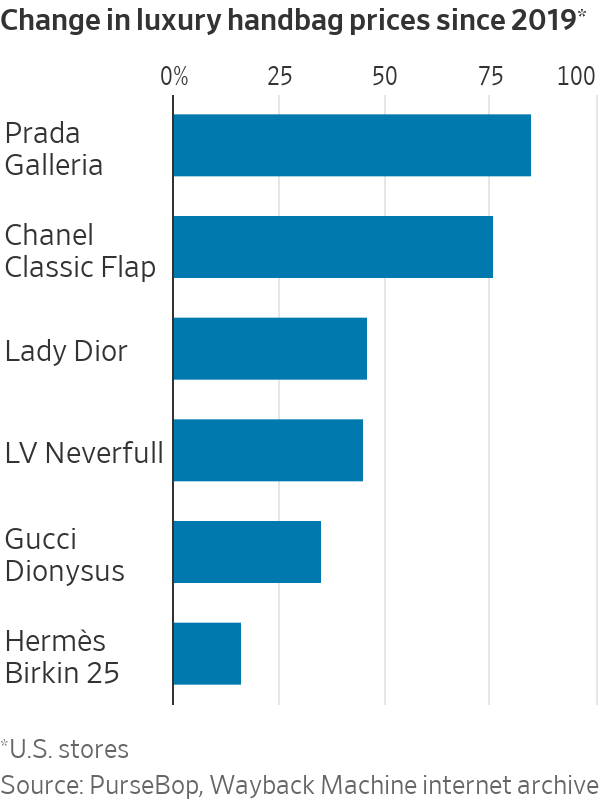

The brand may feel under pressure to defend its reputation as the maker of the world’s most expensive handbags. The “Birkin premium”—the price difference between the Hermès bag and its closest competitor , the Chanel Classic Flap in medium—shrank from 70% in 2019 to 2% last year, according to PurseBop founder Monika Arora. Privately owned Chanel has jacked up the price of its most popular handbag by 75% since before the pandemic.

Eye-watering price increases on luxury brands’ benchmark products are a wider trend. Prada ’s Galleria bag will set shoppers back a cool $4,600—85% more than in 2019, according to the Wayback Machine internet archive. Christian Dior ’s Lady Dior bag and the Louis Vuitton Neverfull are both 45% more expensive, PurseBop data show.

With the U.S. consumer-price index up a fifth since 2019, luxury brands do need to offset higher wage and materials costs. But the inflation-beating increases are also a way to manage the challenge presented by their own success: how to maintain an aura of exclusivity at the same time as strong sales.

Luxury brands have grown enormously in recent years, helped by the Covid-19 lockdowns, when consumers had fewer outlets for spending. LVMH ’s fashion and leather goods division alone has almost doubled in size since 2019, with €42.2 billion in sales last year, equivalent to $45.8 billion at current exchange rates. Gucci, Chanel and Hermès all make more than $10 billion in sales a year. One way to avoid overexposure is to sell fewer items at much higher prices.

Many aspirational shoppers can no longer afford the handbags, but luxury brands can’t risk alienating them altogether. This may explain why labels such as Hermès and Prada have launched makeup lines and Gucci’s owner Kering is pushing deeper into eyewear. These cheaper categories can be a kind of consolation prize. They can also be sold in the tens of millions without saturating the market.

“Cosmetics are invisible—unless you catch someone applying lipstick and see the logo, you can’t tell the brand,” says Luca Solca, luxury analyst at Bernstein.

Most of the luxury industry’s growth in 2024 will come from price increases. Sales are expected to rise by 7% this year, according to Bernstein estimates, even as brands only sell 1% to 2% more stuff.

Limiting volume growth this way only works if a brand is so popular that shoppers won’t balk at climbing prices and defect to another label. Some companies may have pushed prices beyond what consumers think they are worth. Sales of Prada’s handbags rose a meagre 1% in its last quarter and the group’s cheaper sister label Miu Miu is growing faster.

Ramping up prices can invite unflattering comparisons. At more than $2,000, Burberry ’s small Lola bag is around 40% more expensive today than it was a few years ago. Luxury shoppers may decide that tried and tested styles such as Louis Vuitton’s Neverfull bag, which is now a little cheaper than the Burberry bag, are a better buy—especially as Louis Vuitton bags hold their value better in the resale market.

Aggressive price increases can also drive shoppers to secondhand websites. If a barely used Prada Galleria bag in excellent condition can be picked up for $1,500 on luxury resale website The Real Real, it is less appealing to pay three times that amount for the bag brand new.

The strategy won’t help everyone, but for the best luxury brands, stretching the price spectrum can keep the risks of growth in check.

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

What a quarter-million dollars gets you in the western capital.

Alexandre de Betak and his wife are focusing on their most personal project yet.

CIOs can take steps now to reduce risks associated with today’s IT landscape

As tech leaders race to bring Windows systems back online after Friday’s software update by cybersecurity company CrowdStrike crashed around 8.5 million machines worldwide, experts share with CIO Journal their takeaways for preparing for the next major information technology outage.

IT leaders should hold vendors deeply integrated within IT systems, such as CrowdStrike , to a “very high standard” of development, release quality and assurance, said Neil MacDonald , a Gartner vice president.

“Any security vendor has a responsibility to do extensive regression testing on all versions of Windows before an update is rolled out,” he said.

That involves asking existing vendors to explain how they write software, what testing they do and whether customers may choose how quickly to roll out an update.

“Incidents like this remind all of us in the CIO community of the importance of ensuring availability, reliability and security by prioritizing guardrails such as deployment and testing procedures and practices,” said Amy Farrow, chief information officer of IT automation and security company Infoblox.

While automatically accepting software updates has become the norm—and a recommended security practice—the CrowdStrike outage is a reminder to take a pause, some CIOs said.

“We still should be doing the full testing of packages and upgrades and new features,” said Paul Davis, a field chief information security officer at software development platform maker JFrog . undefined undefined Though it’s not feasible to test every update, especially for as many as hundreds of software vendors, Davis said he makes it a priority to test software patches according to their potential severity and size.

Automation, and maybe even artificial intelligence-based IT tools, can help.

“Humans are not very good at catching errors in thousands of lines of code,” said Jack Hidary, chief executive of AI and quantum company SandboxAQ. “We need AI trained to look for the interdependence of new software updates with the existing stack of software.”

An incident rendering Windows computers unusable is similar to a natural disaster with systems knocked offline, said Gartner’s MacDonald. That’s why businesses should consider natural disaster recovery plans for maintaining the resiliency of their operations.

One way to do that is to set up a “clean room,” or an environment isolated from other systems, to use to bring critical systems back online, according to Chirag Mehta, a cybersecurity analyst at Constellation Research.

Businesses should also hold tabletop exercises to simulate risk scenarios, including IT outages and potential cyber threats, Mehta said.

Companies that back up data regularly were likely less impacted by the CrowdStrike outage, according to Victor Zyamzin, chief business officer of security company Qrator Labs. “Another suggestion for companies, and we’ve been saying that again and again for decades, is that you should have some backup procedure applied, running and regularly tested,” he said.

For any vendor with a significant impact on company operations , MacDonald said companies can review their contracts and look for clauses indicating the vendors must provide reliable and stable software.

“That’s where you may have an advantage to say, if an update causes an outage, is there a clause in the contract that would cover that?” he said.

If it doesn’t, tech leaders can aim to negotiate a discount serving as a form of compensation at renewal time, MacDonald added.

The outage also highlights the importance of insurance in providing companies with bottom-line protection against cyber risks, said Peter Halprin, a partner with law firm Haynes Boone focused on cyber insurance.

This coverage can include protection against business income losses, such as those associated with an outage, whether caused by the insured company or a service provider, Halprin said.

The CrowdStrike update affected only devices running Microsoft Windows-based systems , prompting fresh questions over whether enterprises should rely on Windows computers.

CrowdStrike runs on Windows devices through access to the kernel, the part of an operating system containing a computer’s core functions. That’s not the same for Apple ’s Mac operating system and Linux, which don’t allow the same level of access, said Mehta.

Some businesses have converted to Chromebooks , simple laptops developed by Alphabet -owned Google that run on the Chrome operating system . “Not all of them require deeper access to things,” Mehta said. “What are you doing on your laptop that actually requires Windows?”