Is China’s Economic Predicament as Bad as Japan’s? It Could Be Worse

From demographics to decoupling, China faces challenges Japan didn’t after its 1980s bubble

From demographics to decoupling, China faces challenges Japan didn’t after its 1980s bubble

HONG KONG—Starting in the 1990s Japan became synonymous with economic stagnation, as a boom gave way to lethargic growth, declining population and deflation.

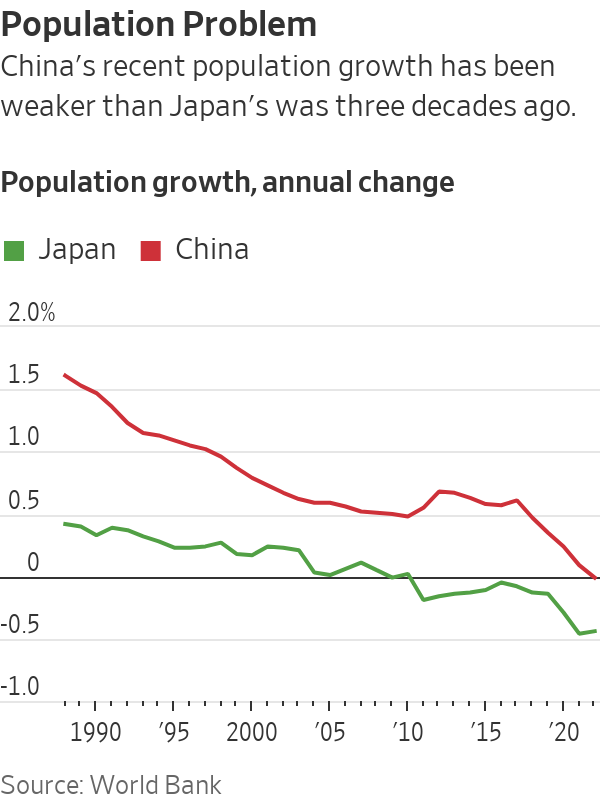

Many economists say China today looks similar. The reality: In many ways its problems are more intractable than Japan’s. China’s public debt levels are higher by some measures than Japan’s were and its demographics are worse. The geopolitical tensions that China is dealing with go beyond the trade frictions Japan once faced with the U.S.

Another headwind: China’s government, which has been cracking down on the private sector in recent years, seems ideologically less inclined than Tokyo was then to support growth.

None of this means China is sure to repeat the years of economic stagnation that Japan is only now showing signs of exiting. It has some advantages that Japan didn’t. Its economic growth in coming years is likely to be well above Japan’s in the 1990s.

Even so, economists say the parallels are a warning for Communist Party leaders in Beijing: If they don’t act more forcefully, the country could get stuck in a protracted period of economic sluggishness similar to Japan’s. Despite piecemeal steps in recent weeks, including modest interest-rate cuts, Beijing has held back on major stimulus to revive growth.

“China’s policy responses so far could put it on track for ‘Japanification,’” said Johanna Chua, chief Asia economist at Citigroup. She believes China’s overall growth prospects could be slowing more sharply than Japan’s.

China today and Japan 30 years ago share many similarities, including high debt levels, an aging population and signs of deflation.

During a long postwar economic expansion, Japan became an export powerhouse that American politicians and corporate executives worried would be unstoppable. Then in the early 1990s, real estate and stock market bubbles burst and the economy hit the skids.

Policy makers cut interest rates to virtually zero, but growth failed to rebound as consumers and companies focused on repaying debt to repair their balance sheets instead of borrowing to finance new spending and investment.

Richard Koo, an economist at the research arm of Japanese investment bank Nomura Securities, famously coined the term “balance sheet recession” to describe the phenomenon.

China, too, has seen a property bubble pop after years of extraordinary economic growth. Chinese consumers are now paying off mortgages early, despite government efforts to get them to borrow and spend more.

Private firms are also reluctant to invest despite lower interest rates, stirring anxiety among economists that monetary easing might be losing its potency in China.

By some measures, China’s asset bubbles aren’t as big. Morgan Stanley estimates that China’s ratio of property value to gross domestic product peaked at 260% in 2020, up from 170% of GDP in 2014; home prices have only fallen slightly since the peak, according to official data. China’s equity markets hit a recent peak of 80% of GDP in 2021 and now sit at 67% of GDP.

In Japan, land values as a percentage of GDP reached 560% of GDP in 1990 before falling back to 394% by 1994, Morgan Stanley estimates. The Tokyo Stock Exchange’s market capitalisation rose to 142% of GDP in 1989 from 34% in 1982.

Also in China’s favour, its urbanisation rate is lower, standing at 65% in 2022, versus Japan’s, which was at 77% in 1988. That could give China more potential to raise productivity and growth as people move to cities and take on nonagricultural jobs.

China’s tighter control over its capital markets means the risk of a sharp appreciation of its currency, which would harm exports, is low. Japan had to deal with a sharp increase in its currency several times in recent decades, which at times added to its economic struggles.

“We believe worries on China being trapped in a balance sheet recession are overdone,” economists from Bank of America recently wrote.

Yet in other ways, China’s problems will be harder to tackle than Japan’s.

Its population is aging faster; it began to decline in 2022. In Japan, that didn’t happen until 2008, nearly two decades after its bubble burst.

Worse, China appears to be entering a period of weaker long-term growth rates before reaching rich-world status, i.e. it is getting old before it gets rich: China’s per capita income was $12,850 in 2022, much lower than Japan in 1991 at $29,080, World Bank data shows.

Then there is the problem of debt. Once off-balance-sheet borrowing by local governments is factored in, total public debt in China reached 95% of GDP in 2022, compared with 62% of GDP in Japan in 1991, according to J.P. Morgan. That limits authorities’ ability to pursue fiscal stimulus.

External pressures also appear to be tougher for China. Japan faced a lot of heat from its trading partners, but as a military ally of the U.S., it never risked a “new Cold War”—as some analysts now describe the U.S.-China relationship. Efforts by the U.S. and its allies to block China’s access to advanced technologies and reduce reliance on Chinese supply chains have sparked a plunge in foreign direct investment into China this year, which could significantly slow growth in the long run.

Many analysts worry Beijing is underestimating the risk of long-term stagnation—and doing too little to avoid it. Moderate cuts to key interest rates, lowering down payment ratios for apartments and recent vocal support for the private sector have done little to revive sentiment so far. Economists including Xiaoqin Pi from Bank of America argue that more coordinated easing in fiscal, monetary and property policies will be needed to put China’s growth back on track.

But President Xi Jinping is ideologically opposed to increasing government support for households and consumers, which he derides as “welfarism.”

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

What a quarter-million dollars gets you in the western capital.

Alexandre de Betak and his wife are focusing on their most personal project yet.

A new study finds that is particularly true for people nearing retirement.

Feeling depressed when the stock market is down? You have plenty of company. According to a recent study, when stock prices fall, the number of antidepressant prescriptions rises.

The researchers examined the connection by first creating local stock indexes, combining companies with headquarters in the same state. Academic research has shown that investors tend to own more local stocks in their portfolios, either because of employee-stock-ownership plans or because they have more familiarity with those companies.

The researchers then looked at about 300 metropolitan statistical areas, which are regions encompassing a city with 50,000 people and the surrounding towns, tracking changes in local stock prices and the number of antidepressant prescriptions in each area over a two-year period. They found that when local stock prices dropped about 12.8% over a two-week period, antidepressant prescriptions increased 0.42% on average. A similar relationship was seen in smaller stock-price drops as well. When local stock prices fell by about 6.4%, antidepressant prescriptions increased about 0.21%.

“Our findings suggest that as the stock market declines, more people experience stress and anxiety, leading to an increase in prescriptions for antidepressants,” says Chang Liu , an assistant professor at Ball State University’s Miller College of Business in Muncie, Ind., and one of the paper’s co-authors. The analysis controlled for other factors that could influence antidepressant usage, like unemployment rates or the season.

In a comparison of age groups, those aged 46 to 55 were the most likely to get antidepressant prescriptions when local stocks dropped.

“People in this age group may be more sensitive to changes in their portfolio compared with a younger cohort, who are further from retirement, and older cohorts who may own less stocks and more bonds since they are nearing retirement,” says Maoyong Fan , a professor at Ball State University and co-author of the study.

When the authors looked at demand for psychotherapy during periods of declining stock prices their findings were similar. When local stock prices dropped by about 12.8% over a two-week period, the number of psychotherapy visits billed to insurance providers increased by about 0.32%. They also found a correlation between local stock returns and certain illnesses associated with depression, such as insomnia, peptic ulcer, abdominal pain, substance abuse and myocardial infarction. But when the authors looked at other insurance claims, like antibiotics prescriptions, they found no relationship with changes in local stock prices.

By contrast, for periods when stocks rise, the authors didn’t see a drop in psychological interventions. They found no statistical relationship between rising local stock prices and the number of antidepressant prescriptions, for example, which the authors believe makes sense.

“Once a patient is prescribed an antidepressant, it’s unlikely that a psychiatrist would stop antidepressant prescriptions immediately,” says Liu.

One practical implication of the study, Liu adds, is that investors should be aware of their emotional state when the market dips before they make investment decisions.