Social-Media Influencers Aren’t Getting Rich—They’re Barely Getting By

Platforms are paying less for popular posts, brands are pickier about partnerships and a possible TikTok ban looms

Platforms are paying less for popular posts, brands are pickier about partnerships and a possible TikTok ban looms

Many people dream of becoming social-media stars like YouTube’s MrBeast or TikTok’s Charli D’Amelio . But for most who pursue careers as content creators, just making ends meet is a lofty goal.

Clint Brantley has been a full-time creator for three years, posting videos on TikTok, YouTube and Twitch where he comments on news and trends related to the online game “Fortnite.” Despite having more than 400,000 followers, and posts that average 100,000 views, his income last year was less than the median annual pay for full-time U.S. workers in 2023—$58,084, based on Bureau of Labor Statistics data.

The 29-year-old is hesitant to commit to an apartment lease because the money he gets, mainly from online tips and sponsorship deals, arrives randomly and could vanish at any moment. For now, he’s living with his mom in Washington state.

“I’m vulnerable,” he says.

Earning a decent, reliable income as a social-media creator is a slog—and it’s getting harder. Platforms are doling out less money for popular posts and brands are being pickier about what they want out of sponsorship deals. The real possibility of TikTok potentially shutting down in 2025 is adding to creators’ anxiety over whether they can afford to stick with the job for the long haul.

Hundreds of millions of people around the globe regularly post videos and photos to entertain or educate social-media users. About 50 million earn money from it, according to a 2023 report from Goldman Sachs . The investment bank expects the number of creator-earners to grow at an annual rate of 10% to 20% through 2028, crowding the field even further. The Labor Department doesn’t track wages for these creators, also known as influencers.

It can take months or years to earn money as a creator, often through a combination of direct revenue from social-media platforms, sponsorship deals, merchandise sales and affiliate links. But those who stick with it eventually see some returns, surveys show. Creators say that’s because you can learn what kind of posts most resonate with an audience, which can lead to more followers and, in turn, more moneymaking opportunities.

But money doesn’t mean big bucks . Last year, 48% of creator-earners made $15,000 or less, according to NeoReach, an influencer marketing agency. Only 13% made more than $100,000.

The gap reflects multiple factors, including whether creators work full- or part-time, the kind of content they put out and when they started. People who jumped into the space during the height of Covid-19 lockdowns—and who focused on a niche such as fashion, investing or lifestyle hacks—say they benefited from the surge in social-media use during that time.

A small number of creators shot to fame, propelling the occupation to the top of career wish lists for many teens (and adults). But behind the scenes, creators say the job is gruelling. They need to constantly produce compelling posts or risk losing momentum. They spend their days planning, filming and editing posts while also working to make inroads with advertisers and interacting with fans.

“It is a lot more work than most people realise,” says Emarketer analyst Jasmine Enberg. “Creators who make a living doing it have been at it for many years. Most are not overnight sensations.”

Like other self-employed professionals, creators don’t get paid time off, healthcare benefits, retirement contributions and other perks that companies typically provide for their workers. That reality, coupled with stubbornly high inflation and mortgage rates , is making it more difficult to get by as a creator.

“Everything is more expensive, especially groceries,” says Jason Cooper of Mobile, Ala.

A few years ago, Cooper dreamed up a sassy sock puppet named Sock Cop, who cracks dad jokes in live and recorded videos for TikTok and Twitch. He currently makes $500 to $600 a month, almost entirely from tips.

He thinks he could probably haul in a lot more if he went full-time. But with no guarantee, the 37-year-old father doesn’t want to quit his marketing job and risk losing health coverage. He now spends a few hours in the evening and on weekends on Sock Cop. If he had more time, he would feel the need to constantly make videos.

“You’ve got to feed the beast,” says Cooper.

TikTok’s $1 billion creator fund, which ran from 2020 to 2023, doled out money to eligible creators for posting to the platform. Others joined in. YouTube’s TikTok competitor, Shorts, allowed creators to earn anywhere from $100 to $10,000 a month with its temporary fund. Instagram’s Reels Play bonus program rewarded creators with fluctuating payouts. Snapchat ’s Spotlight rewards program gave $1 million a day to the platform’s top creators.

Today, the platforms have revamped or completely changed how they pay creators—doing away with their funds.

Qualifications for TikTok’s current rewards program include having an account with at least 10,000 followers with a minimum of 100,000 views in the past month. Instagram is currently testing a seasonal, invitation-only program that rewards creators for sharing Reels and photos.

YouTube debuted an ad-revenue share model last year, in which qualifying creators with more than 1,000 subscribers and 10 million public Shorts views in the past 90 days receive 45% of revenue from ads that occur between posts. Snapchat has a program that gives creators who meet certain criteria, such as having at least 50,000 followers and 25 million monthly views, a portion of the ad revenue that appears between Stories. Its Spotlight program also continues to dole out money to creators.

Creators who opt into these programs or bonuses aren’t guaranteed a significant payday.

Yuval Ben-Hayun originally became popular on TikTok in 2020 because of his posts about the word-puzzle game Wordle. The 29-year-old New Yorker eventually expanded into linguistic and other education content, and by early 2023, was able to support himself and his bills of over $4,000 a month.

TikTok had closed its fund by then but was testing its creator rewards program. Ben-Hayun said in March he received about $200 to $400 per million views, and it’s steadily declined since then—even as his follower count reached 2.9 million.

The followers are still there, but the money isn’t. He recently hit a new low, receiving only $120 for a video with 10 million views.

Danisha Carter is frustrated that TikTok and other platforms sold the idea of content creation as a job, but later withdrew the financial incentives. Thanks to creators’ efforts, she says, consumers are now hooked on social feeds, bringing the platforms billions of dollars in annual revenue.

The 26-year-old has 1.8 million TikTok followers, and her posts about beauty and exercise, along with opinions on topics ranging from dating to online bullying, regularly receive hundreds of thousands of views. TikTok has paid her a total of $12,000, Carter says. She sells merchandise for additional income, bringing in about $5,000 last year.

“Creators should be paid a fair percentage based on what the apps are making off creators,” says Carter. “There should be more transparency into how we’re paid, and it should be consistent.”

A TikTok spokeswoman declined to comment.

YouTube said it paid more than $70 billion to creators, artists and media companies in the past three years, and more than 25% of channels in the ad-revenue share model are now making money through it. “We remain committed to putting our full energy into what matters most for our creators, viewers and advertisers,” a spokeswoman said.

Many creators and advertisers credit TikTok, which pioneered the short-form video genre, with driving stronger engagement than its industry peers. TikTok has gained more than 170 million users in the U.S. since its launch in 2016—including, Pew Research Center says, a third of American adults. They spend an average of 78 minutes a day on the app, according to market-intelligence firm Sensor Tower.

TikTok may not be available in the U.S. for much longer, at least not in its current form. In April, President Biden signed a bill into law that will force a sale or ban of the app by Jan. 19, 2025. U.S. lawmakers have expressed worries that TikTok poses a national security risk. TikTok’s parent company, Beijing-based ByteDance, has said it can’t and won’t sell its U.S. operations by the deadline.

ByteDance sued the U.S. government, alleging the new law violates its First Amendment rights. Several U.S. creators also sued. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit will hear arguments in September for both cases.

“To lose TikTok would be kind of devastating,” says Brandon Granberg , a 31-year-old creator from Bayville, N.J., known for interacting with strangers in public places in silly ways.

Granberg struggled for years to attract viewers on the app before one viral post two years ago took his follower count from 5,000 to more than one million. Recently he made $1,000 from a TikTok program that launched last year called TikTok Creative Challenge, which allows creators to earn money by making video ads for brands that don’t appear on their personal profiles. He also earned $2,800 for producing four TikTok videos promoting a website for people with foot fetishes. Granberg says he found it creepy, but did it because he needed the money.

While he hasn’t landed many other sponsored posts, he’s grown his income significantly by making marketing videos for small businesses over the past year. Most clients find Granberg on TikTok. “If it gets banned, it will definitely hurt me,” he says.

This year, U.S. social-media creators as a whole are expected to make $13.7 billion, according to Emarketer. The research firm projects the majority of that—$8.14 billion, or 59%—will come from brand sponsorships.

Advertisers have always led in compensating creators, paying out far more money than the social-media platforms and fans who buy merchandise or dole out tips. But these days, advertisers expect more from creators than just large followings, according to agency and talent representatives. They want to see evidence of strong engagement in the form of saved and shared posts, plus the demographics of creators’ audiences.

“Brands are looking at metrics that are far less predictable for creators and also very difficult to price yourself on,” says Sarah Peretz, a business-strategy consultant in Los Angeles who helps creators negotiate partnerships and deals with advertisers.

Some brands are more controlling than in the past, says Sarah Steele , a 34-year-old creator in Tulsa, Okla., who started making TikTok videos about being a working mom in 2020. “Now it’s, ‘We’re paying you and this is what we want you to say.’ ”

Earlier this year, Steele says an advertiser insisted she cite legal disclaimers in a series of sponsored Instagram posts. “It felt like I was reading off a teleprompter,” she says. “As a consumer it even turned me off to the brand a little bit.”

Creators, meanwhile, are having a tougher time attracting viewers, thanks to algorithm changes and other factors beyond their control. And while more advertisers are looking to partner with creators than in the past, “increased activity leads to increased competition,” says Peretz.

Another change is that advertisers now prefer to work with just a handful of creators on long-lasting deals rather than experiment with several on one-off projects, says Jess Hunichen, of Shine Talent Group.

Hunichen co-founded the talent-management agency in 2015, when TikTok didn’t exist and influencer marketing was still relatively new. Back then, an average deal size between an influencer and brand was usually below $1,000. Now, the average deal per campaign is around $10,000, she says.

Ronit Halmos of Los Angeles began making TikTok videos earlier this year that she describes as quick-reviews of restaurants, bars and more “with some sass and attitude.”

The 27-year-old, a full-time technology recruiter, recently landed her first advertiser deal. A kombucha brand asked her to make a 30-second post featuring her take on a line of flavors. Though it ended up getting less attention from viewers than her usual fare, she made $1,500 from about 30 minutes of work.

Tyler Haven , a 27-year-old traveling around the Pacific Northwest, charges $250 to $300 to make promotional videos that brands can post to their own social channels, and around $1,200 for posts that appear on either his Instagram account with more than 41,000 followers or his TikTok account with more than 10,000 followers.

Since January, he’s been posting videos documenting his “van-life” with his wife, Oak Haven: Their primary residence is a fully paid, fully decked-out 2004 Mercedes Sprinter T1N.

Haven said it’s been easy to grow his following organically. He believes it’s because his posts don’t depict some unattainable, picture-perfect life.

He quit his job in June to pursue full-time content creation.

“Even if I were to make $2,000 a month, which is absolutely nothing—that’s less than most people’s rent—I could live on that,” Haven says.

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

What a quarter-million dollars gets you in the western capital.

Alexandre de Betak and his wife are focusing on their most personal project yet.

Subsidised minivans, no income taxes: Countries have rolled out a range of benefits to encourage bigger families, with no luck

Imagine if having children came with more than $150,000 in cheap loans, a subsidised minivan and a lifetime exemption from income taxes.

Would people have more kids? The answer, it seems, is no.

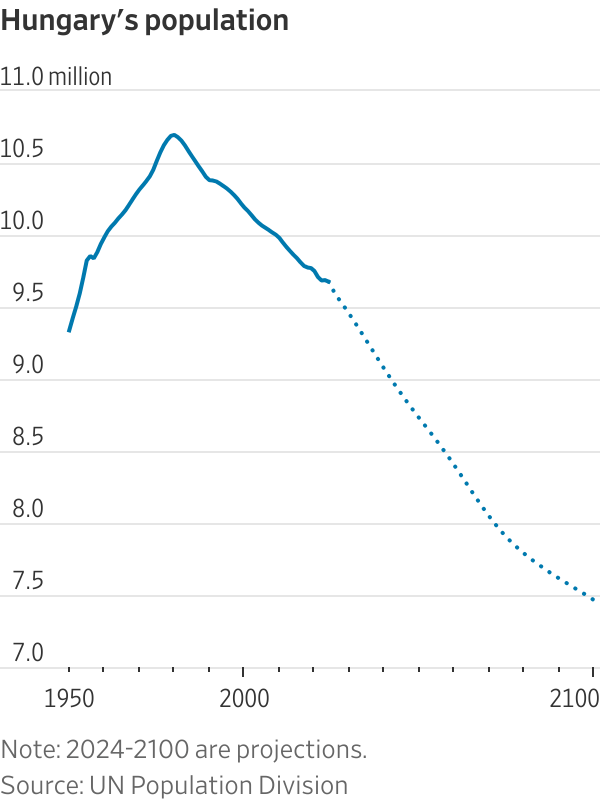

These are among the benefits—along with cheap child care, extra vacation and free fertility treatments—that have been doled out to parents in different parts of Europe, a region at the forefront of the worldwide baby shortage. Europe’s overall population shrank during the pandemic and is on track to contract by about 40 million by 2050, according to United Nations statistics.

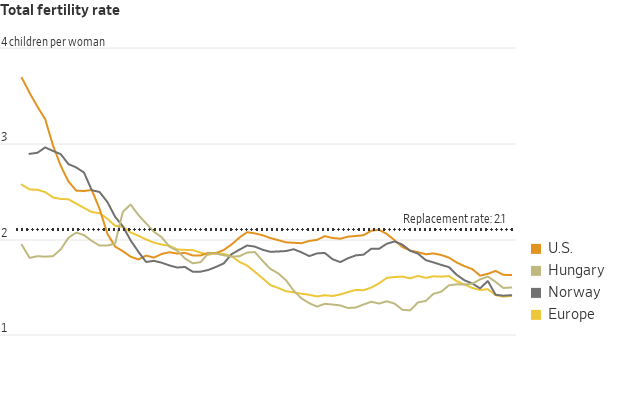

Birthrates have been falling across the developed world since the 1960s. But the decline hit Europe harder and faster than demographers expected—a foreshadowing of the sudden drop in the U.S. fertility rate in recent years.

Reversing the decline in birthrates has become a national priority among governments worldwide, including in China and Russia , where Vladimir Putin declared 2024 “the year of the family.” In the U.S., both Kamala Harris and Donald Trump have pledged to rethink the U.S.’s family policies . Harris wants to offer a $6,000 baby bonus. Trump has floated free in vitro fertilisation and tax deductions for parents.

Europe and other demographically challenged economies in Asia such as South Korea and Singapore have been pushing back against the demographic tide with lavish parental benefits for a generation. Yet falling fertility has persisted among nearly all age groups, incomes and education levels. Those who have many children often say they would have them even without the benefits. Those who don’t say the benefits don’t make enough of a difference.

Two European countries devote more resources to families than almost any other nation: Hungary and Norway. Despite their programs, they have fertility rates of 1.5 and 1.4 children for every woman, respectively—far below the replacement rate of 2.1, the level needed to keep the population steady. The U.S. fertility rate is 1.6.

Demographers suggest the reluctance to have kids is a fundamental cultural shift rather than a purely financial one.

“I used to say to myself, I’m too young. I have to finish my bachelor’s degree. I have to find a partner. Then suddenly I woke up and I was 28 years old, married, with a car and a house and a flexible job and there were no more excuses,” said Norwegian Nancy Lystad Herz. “Even though there are now no practical barriers, I realised that I don’t want children.”

Both Hungary and Norway spend more than 3% of GDP on their different approaches to promoting families—more than the amount they spend on their militaries, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

Hungary says in recent years its spending on policies for families has exceeded 5% of GDP. The U.S. spends around 1% of GDP on family support through child tax credits and programs aimed at low-income Americans.

Hungary’s subsidised housing loan program has helped almost 250,000 families buy or upgrade their homes, the government says. Orsolya Kocsis, a 28-year-old working in human resources, knows having kids would help her and her husband buy a larger house in Budapest, but it isn’t enough to change her mind about not wanting children.

“If we were to say we’ll have two kids, we could basically buy a new house tomorrow,” she said. “But morally, I would not feel right having brought a life into this world to buy a house.”

Promoting baby-making, known as pro natalism, is a key plank of Prime Minister Viktor Orbán ’s broader populist agenda . Hungary’s biennial Budapest Demographic Summit has become a meeting ground for prominent conservative politicians and thinkers. Former Fox News anchor Tucker Carlson and JD Vance, Trump’s vice president pick, have lauded Orbán’s family policies.

Orbán portrays having children inside what he has called a “traditional” family model as a national duty, as well as an alternative to immigration for growing the population. The benefits for child-rearing in Hungary are mostly reserved for married, heterosexual, middle-class couples. Couples who divorce lose subsidised interest rates and in some cases have to pay back the support.

Hungary’s population, now less than 10 million, has been shrinking since the 1980s. The country is about the size of Indiana.

“Because there are so few of us, there’s always this fear that we are disappearing,” said Zsuzsanna Szelényi, program director at the CEU Democracy Institute and author of a book on Orbán.

Hungary’s fertility rate collapsed after the fall of the Soviet Union and by 2010 was down to 1.25 children for every woman. Orbán, a father of five, and his Fidesz party swept back into power that year after being ousted in the early 2000s. He expanded the family support system over the next decade.

Hungary’s fertility rate rose to 1.6 children for every woman in 2021. Ivett Szalma, an associate professor at Corvinus University of Budapest, said that like in many other countries, women in Hungary who had delayed having children after the global financial crisis were finally catching up.

Then progress stalled. Hungary’s fertility rate has fallen for the past two years. Around 51,500 babies have been born there this year through August, a 10% drop compared with the same period last year. Many Hungarian women cite underfunded public health and education systems and difficulties balancing work and family as part of their hesitation to have more children.

Anna Nagy, a 35-year-old former lawyer, had her son in January 2021. She received a loan of about $27,300 that she didn’t have to start paying back until he turned 3. Nagy had left her job before getting pregnant but still received government-funded maternity payments, equal to 70% of her former salary, for the first two years and a smaller amount for a third year.

She used to think she wanted two or three kids, but now only wants one. She is frustrated at the implication that demographic challenges are her responsibility to solve. Economists point to increased immigration and a higher retirement age as other offsets to the financial strains on government budgets from a declining population.

“It’s not our duty as Hungarian women to keep the nation alive,” she said.

Hungary is especially generous to families who have several children, or who give birth at younger ages. Last year, the government announced it would restrict the loan program used by Nagy to women under 30. Families who pledge to have three or more children can get more than $150,000 in subsidised loans. Other benefits include a lifetime exemption from personal taxes for mothers with four or more kids, and up to seven extra annual vacation days for both parents.

Under another program that’s now expired, nearly 30,000 families used a subsidy to buy a minivan, the government said.

Critics of Hungary’s family policies say the money is wasted on people who would have had large families anyway. The government has also been criticised for excluding groups such as the minority Roma population and poorer Hungarians. Bank accounts, credit histories and a steady employment history are required for many of the incentives.

Orbán’s press office didn’t respond to requests for comment. Tünde Fűrész, head of a government-backed demographic research institute, disagreed that the policies are exclusionary and said the loans were used more heavily in economically depressed areas.

Government programs weren’t a determining factor for Eszter Gerencsér, 37, who said she and her husband always wanted a big family. They have four children, ages 3 to 10.

They received about $62,800 in low-interest loans through government programs and $35,500 in grants. They used the money to buy and renovate a house outside of Budapest. After she had her fourth child, the government forgave $11,000 of the debt. Her family receives a monthly payment of about $40 a month for each child.

Most Hungarian women stay home with their children until they turn 2, after which maternity payments are reduced. Publicly run nurseries are free for large families like hers. Gerencsér worked on and off between her pregnancies and returned full-time to work, in a civil-service job, earlier this year.

She still thinks Hungarian society is stacked against mothers and said she struggled to find a job because employers worried she would have to take lots of time off.

The country’s international reputation as family-friendly is “what you call good marketing,” she said.

Norway has been incentivising births for decades with generous parental leave and subsidised child care. New parents in Norway can share nearly a year of fully paid leave, or around 14 months at 80% pay. More than three months are reserved for fathers to encourage more equal caregiving. Mothers are entitled to take at least an hour at work to breast-feed or pump.

The government’s goal has never been explicitly to encourage people to have more children, but instead to make it easier for women to balance careers and children, said Trude Lappegard, a professor who researches demography at the University of Oslo. Norway doesn’t restrict benefits for unmarried parents or same-sex couples.

Its fertility rate of 1.4 children per woman has steadily fallen from nearly 2 in 2009. Unlike Hungary, Norway’s population is still growing for now, due mostly to immigration.

“It is difficult to say why the population is having fewer children,” Kjersti Toppe, the Norwegian Minister of Children and Families, said in an email. She said the government has increased monthly payments for parents and has formed a committee to investigate the baby bust and ways to reverse it.

More women in Norway are childless or have only one kid. The percentage of 45-year-old women with three or more children fell to 27.5% last year from 33% in 2010. Women are also waiting longer to have children—the average age at which women had their first child reached 30.3 last year. The global surge in housing costs and a longer timeline for getting established in careers likely plays a role, researchers say. Older first-time mothers can face obstacles: Women 35 and older are at higher risk of infertility and pregnancy complications.

Gina Ekholt, 39, said the government’s policies have helped offset much of the costs of having a child and allowed her to maintain her career as a senior adviser at the nonprofit Save the Children Norway. She had her daughter at age 34 after a round of state-subsidised IVF that cost about $1,600. She wanted to have more children but can’t because of fertility issues.

She receives a monthly stipend of about $160 a month, almost fully offsetting a $190 monthly nursery fee.

“On the economy side, it hasn’t made a bump. What’s been difficult for me is trying to have another kid,” she said. “The notion that we should have more kids, and you’re very selfish if you have only had one…those are the things that took a toll on me.”

Her friend Ewa Sapieżyńska, a 44-year-old Polish-Norwegian writer and social scientist with one son, has helped her see the upside of the one-child lifestyle. “For me, the decision is not about money. It’s about my life,” she said.