The Inside Tale of Tesla’s Fall to Earth

Sales are dropping. It’s cutting prices. And its latest big bets have yet to pan out. Can the world’s most valuable carmaker get its mojo back?

Sales are dropping. It’s cutting prices. And its latest big bets have yet to pan out. Can the world’s most valuable carmaker get its mojo back?

Tesla Chief Executive Elon Musk has spent years trying to build the automaker of the future. It’s the electric-car company of the present that’s now giving him trouble.

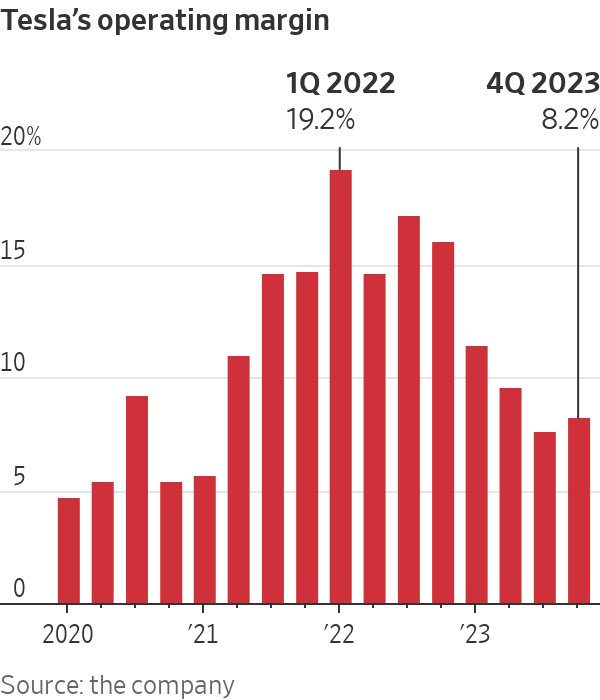

After a period of rapid expansion, the company has seen its sales fall and its once-enviable margins shrink. For the first time in years, the biggest question for Tesla is not whether it will be able to make enough cars, but whether people will buy them.

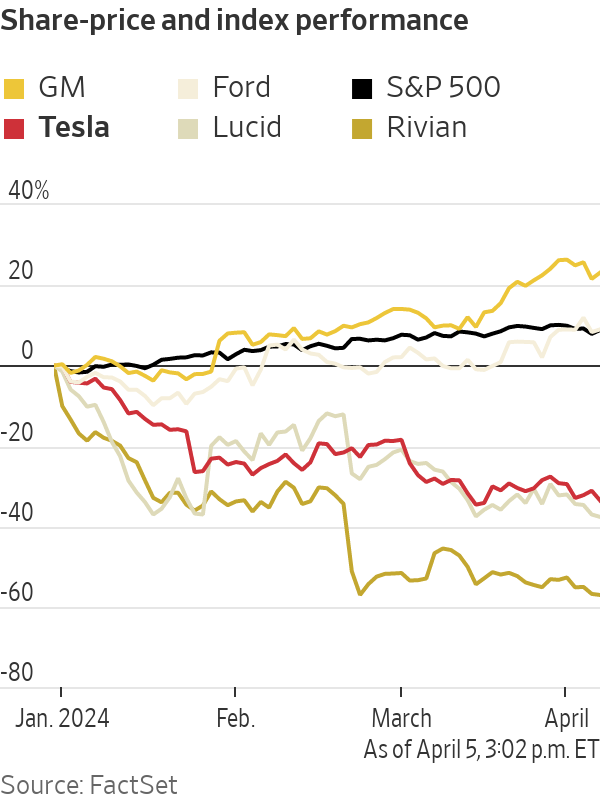

The company’s stock, down 34% this year, has been the worst performer in the S&P 500 index. While Tesla remains the world’s most valuable automaker by a wide margin, its market capitalisation has tumbled by more than half since it peaked in 2021.

Consumer appetite for electric vehicles is cooling. The core of Tesla’s lineup is dated. The company has been cutting prices to spur demand. Big, moonshot bets have not panned out as Musk predicted—at least not yet. And Chinese carmakers are now the ones that look like nimble, tech-savvy upstarts.

Musk’s attention, meanwhile, has sometimes been elsewhere. He bought Twitter, sold some Tesla stock along the way and started an artificial-intelligence company . Of late, he has been picking fights with everyone from OpenAI to Disney Chief Executive Bob Iger . Surveys suggest his public persona has alienated some would-be Tesla buyers.

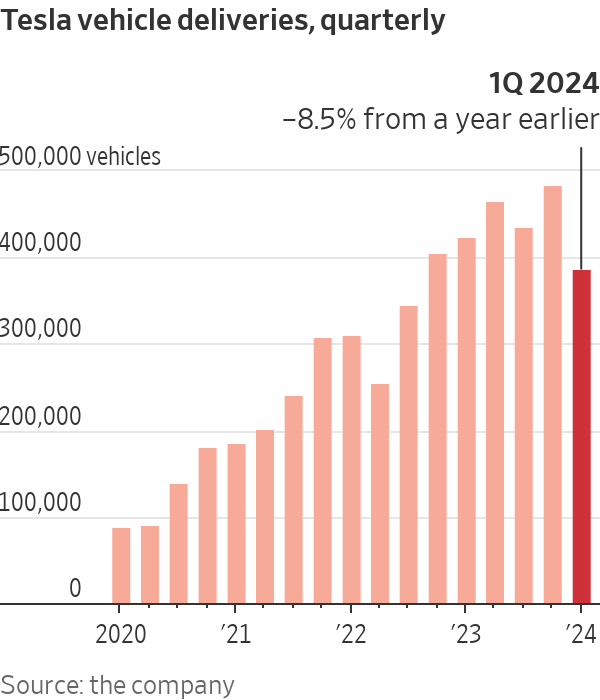

This week, the company reported its first year-over-year decline in quarterly deliveries since 2020—a result that badly missed Wall Street’s expectations.

Musk’s company remains a formidable player in the electric-vehicle market globally and is the clear leader in the U.S. It is still making money on its vehicles, while many established car companies are struggling to turn a profit on their EVs, after committing tens of billions of dollars to expand their offerings. But the boom times of Tesla’s past have faded, and the bright future imagined by Musk—where people will ride around in fully autonomous Teslas—remains distant.

“Tesla is going from the golden era to a really challenging era,” said Mark Fields , a former CEO of Ford Motor who now serves on several corporate boards. Tesla and Musk didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Three years ago, Tesla appeared all but unstoppable.

After years of financial uncertainty and production challenges, the company had turned a corner and was delivering quarter after quarter of record profit.

Its factories were humming , even as a global shortage of semiconductors led many rivals to curtail auto production. Consumer demand was strong enough that Tesla was hiking prices, and waiting lists for new vehicles grew long enough that some buyers were paying a premium for lightly used ones.

As automakers set about remaking themselves in Tesla’s image, Musk—a master salesman with an uncanny knack for inspiring investors to believe in his vision —sought to catch the next market wave: artificial intelligence.

At a Tesla recruiting event in the summer of 2021, the billionaire took the stage in Palo Alto, Calif., dressed all in black, as is his custom.

Tesla had for years been working to develop technology that would allow a computer to assume more of the driving tasks, rolling out the software as part of its Autopilot system.

In an attempt to emphasise Tesla’s might in the artificial-intelligence space—and ambitions beyond the competitive, traditionally low-margin automotive business—Musk unveiled the company’s latest effort: a friendly humanoid robot. The robot, Optimus, was not ready yet. In its place, a human dressed in a robot costume danced on stage.

“Tesla is much more than an electric-car company,” Musk told the crowd. “In the future, physical work will be a choice.”

In late October 2021, rental-car company Hertz Global Holdings said it was ordering 100,000 Tesla vehicles as it looked to expand its fleet of EVs. For investors, the deal was a sign that EVs were becoming mainstream—and soon more drivers would have an opportunity to try one.

Tesla’s market value eventually peaked above $1.2 trillion in early November, up more than 2,000% in two years.

The euphoria was short-lived.

Musk soon began unloading Tesla stock, embarking on a spree that continued for more than a year and resulted in his selling more than $39 billion in shares. The sales—executed in part to fund Musk’s eventual purchase of Twitter—spooked the market and weighed on Tesla’s stock.

The surprises kept coming in 2022.

On a late-January earnings call, Musk revealed Tesla would not be introducing any new models that year, attributing the decision to supply-chain constraints. Instead, the company would churn out as many of its existing models as possible.

Tesla sold four models at the time, but just two drove the lion’s share of the company’s sales: the Model Y sport-utility vehicle and the Model 3 sedan.

Plans for a $25,000 car—a model Musk had teased in late 2020 and said likely would be ready in three years—had been put on ice.

“We have enough on our plate right now,” Musk said.

The move was risky. In the car business, new and redesigned models are critical to holding buyers’ interest and maintaining pricing power.

Analysts were perplexed. One questioned whether Tesla could hit its growth targets with fewer than a half-dozen passenger-vehicle models in its lineup.

Musk brushed off the concern. Instead, he alluded to his vision for a future where Teslas would be able to operate autonomously around the clock—making them even more valuable.

“It’s apparent from the questions that the gravity of Full Self-Driving is not fully appreciated,” Musk said, referring to a souped-up version of Tesla’s driver-assistance technology. (The system doesn’t currently make Tesla vehicles autonomous.)

As the year wore on, investors grew increasingly jittery. Musk’s pursuit of Twitter only amplified concerns on Wall Street that the Tesla CEO was not focused enough on his carmaker.

“Twitter is a distraction,” Gary Black, managing partner of the Future Fund, a Tesla investor, said at the time. “All of the space has been sucked up by him talking about Twitter, and so you don’t hear him tweeting about EVs.”

Warning signs flashed in China, where wait times for new Teslas fell to about a month as of September 2022, from four-plus months in the spring, according to Bernstein Research.

Tesla executives, including chief designer Franz von Holzhausen, pressed Musk to revive plans for the company’s more affordable, mass-market car, arguing it was necessary for Tesla to reach its growth targets, according to Walter Isaacson ’s biography of the CEO. Musk had been more interested in developing autonomous cars that could operate in a robotaxi fleet.

“Our responsibility is to try to get as many people into an EV as possible,” von Holzhausen told The Wall Street Journal earlier this year.

And while he is optimistic about the promise of self-driving cars and encouraged by Tesla’s recent progress, von Holzhausen said the transition will not be simple.

“Maybe I’m more pragmatic about it, but I think autonomy is…it’s going to be a challenge,” he said. “It’s still sci-fi to a lot of people.”

In late October, Tesla cut prices in China by an average of around 7%, according to Bernstein.

Soon after, it began offering temporary discounts on its most popular models in the U.S.—by $3,750 at first, then $7,500 plus 10,000 miles of free fast-chargin g if customers took delivery before year-end.

Tesla’s 2022 ended on a downbeat note. Its annual vehicle deliveries—up 40% over the prior year— fell short of the company’s initial goal and underperformed Wall Street’s expectations. The stock suffered its worst annual performance on record, declining 65%.

By early January 2023, it became clear within Tesla’s finance department that the company needed to take more aggressive action to move cars, people familiar with the matter said.

Tesla had opened two new factories in 2022—one in Germany and another in Texas—expanding its production capacity roughly 80% in less than a year. Unsold inventory climbed to 13 days’ worth of supply in the final three months of 2022, from just four days in the second quarter, according to Tesla’s financial disclosures.

As January unfolded, orders weren’t keeping pace with internal forecasts, one of the people said.

Employees developed a plan that called for Tesla to cut prices more permanently, an unusual strategy in an industry where companies typically try to be more discreet with their incentives.

Elsewhere in the auto industry, Tesla’s rivals were unleashing a barrage of new EV models, including ones designed to directly compete with the Model Y and Model 3.

On a Thursday night in January 2023, Tesla quietly updated its website, slashing prices across its lineup, in some cases by nearly 20%.

Tesla made cuts that were even deeper than the finance department had initially proposed, the people familiar with the matter said.

For Musk, it was a calculated gamble. Tesla’s double-digit operating margins meant it could better absorb the price cuts than rivals, and the move would also put the squeeze on competitors—many of which were losing money on their EVs.

Across the Atlantic, Vincent Cobée, then-CEO of Stellantis ’s Citroën brand, was at the Brussels Motor Show when a journalist told him about Tesla’s price cuts.

Cobée’s first thought: “He’s completely nuts.”

Then: “We’re in deep trouble,” he recalled later.

The maneouvre did boost sales at Tesla—for a time. The company’s vehicle prices fell by an average of 12% globally in the first half of 2023, and deliveries rose 19% compared with the prior six months, according to Wells Fargo.

But in the second half of 2023, as Tesla continued to lower prices and layer on incentives, the company’s vehicle-delivery growth slowed to 3%, compared with the first half—a figure that Wells Fargo analysts described as “concerningly low.”

Some in the auto industry were also starting to sour on electric vehicles.

Dealers who once were bullish about the technology began worrying about the cars stacking up on their lots. Companies that had been racing to scale up EV production suddenly began delaying their investments and shifting their attention to hybrids, which were selling well.

For Tesla, the only new model on the horizon was the Cybertruck—a long-delayed and difficult-to-manufacture pickup truck that eventually hit the market in November . Even so, the model is only available in North America, and Musk has warned it is unlikely to generate significant cash flow before the end of this year.

In China, the world’s largest car market and a production hub for Tesla, a price war had already broken out. The country’s leading EV maker, BYD, and other Chinese car manufacturers were mounting their own offensive, rapidly releasing more affordable EVs that were winning over the domestic market and beginning to make inroads overseas.

In January of this year, Hertz delivered another blow, saying it was selling about a third of its global EV fleet —much of it made up of Tesla vehicles. The rental-car company had previously flagged problems with fast-falling EV resale values and pricey repairs.

Then came the news from earlier this week: Tesla delivered 386,810 vehicles globally in the first three months of 2024, down 8.5% from a year earlier . It was the company’s lowest quarterly performance since the third quarter of 2022.

Wall Street analysts had slashed their expectations for Tesla’s first-quarter performance in the weeks before the disclosure on Tuesday, but the company still came up short.

Musk has sought to quell concerns by describing the company as being in between two growth waves—the first driven by the Model 3 and Model Y, the second to be propelled by the company’s next generation of vehicles, including the much-anticipated low-cost car , which he said in January is due to enter production in late 2025.

In recent weeks, employees were told to prioritise development of a robotaxi, according to a person familiar with the matter.

Reuters on Friday reported that Tesla had canceled plans for the inexpensive car. Musk denied the report on X, as Twitter is now known. Hours later, he added that Tesla plans to unveil its robotaxi model in August.

As Musk has used his social-media platform to address polarising topics such as immigration and race, there is evidence that Musk is doing Tesla no favours with his extracurricular activities.

The company’s reputation among potential U.S. buyers has taken a hit since Musk acquired Twitter, according to market-intelligence firm Caliber. The automaker’s “consideration” rate—where survey respondents said whether they are very likely to buy, or continue buying, products from Tesla—fell from 46% to 35% between September 2022 and this March, Caliber said.

As Tesla’s profitability has weakened, Musk has talked up the potential of the company’s autonomous-driving strategy.

“Most people still have no idea how crushingly good Tesla FSD will get,” he posted on X in late March. “Cars will take you where you want automatically, just like getting in an elevator and pressing a button, something that also used to be manual.”

Despite the recent stock decline, Tesla’s valuation—$525 billion at Friday’s close—still towers over those of other automakers.

Many investors remain confident that Musk, who has defied the odds many times before, can deliver on this vision. Some, such as Owuraka Koney, a managing director at investment manager Jennison Associates, are betting Tesla will be able to generate ample revenue by selling downloadable software, such as its driver-assistance technology, long after it makes that initial car sale.

Said Koney: “We remain very bullish over the long-term.”

— Ryan Felton, Tim Higgins, Mike Colias and Sean McLain contributed to this article.

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

What a quarter-million dollars gets you in the western capital.

Alexandre de Betak and his wife are focusing on their most personal project yet.

Subsidised minivans, no income taxes: Countries have rolled out a range of benefits to encourage bigger families, with no luck

Imagine if having children came with more than $150,000 in cheap loans, a subsidised minivan and a lifetime exemption from income taxes.

Would people have more kids? The answer, it seems, is no.

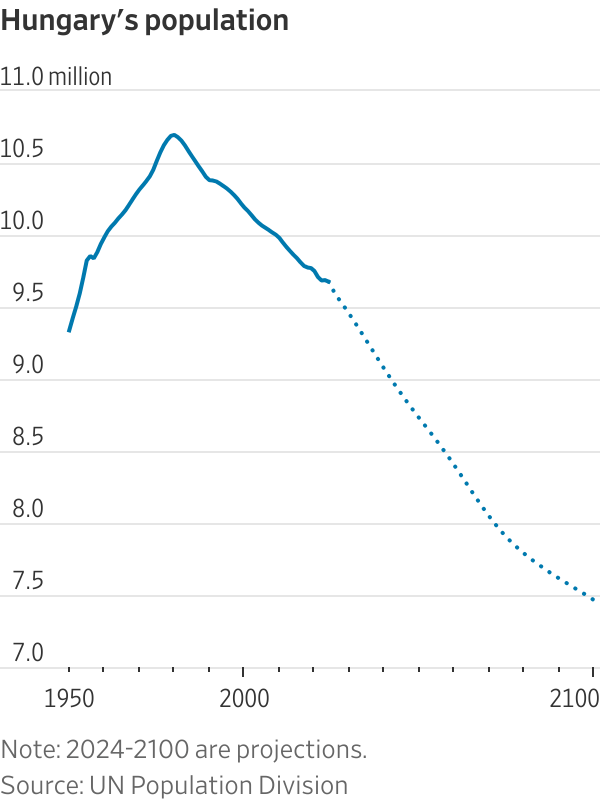

These are among the benefits—along with cheap child care, extra vacation and free fertility treatments—that have been doled out to parents in different parts of Europe, a region at the forefront of the worldwide baby shortage. Europe’s overall population shrank during the pandemic and is on track to contract by about 40 million by 2050, according to United Nations statistics.

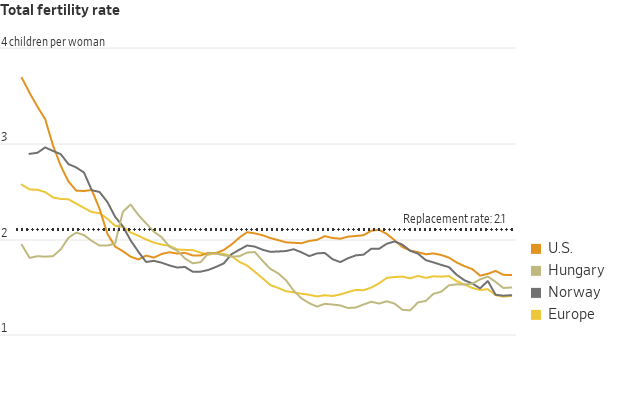

Birthrates have been falling across the developed world since the 1960s. But the decline hit Europe harder and faster than demographers expected—a foreshadowing of the sudden drop in the U.S. fertility rate in recent years.

Reversing the decline in birthrates has become a national priority among governments worldwide, including in China and Russia , where Vladimir Putin declared 2024 “the year of the family.” In the U.S., both Kamala Harris and Donald Trump have pledged to rethink the U.S.’s family policies . Harris wants to offer a $6,000 baby bonus. Trump has floated free in vitro fertilisation and tax deductions for parents.

Europe and other demographically challenged economies in Asia such as South Korea and Singapore have been pushing back against the demographic tide with lavish parental benefits for a generation. Yet falling fertility has persisted among nearly all age groups, incomes and education levels. Those who have many children often say they would have them even without the benefits. Those who don’t say the benefits don’t make enough of a difference.

Two European countries devote more resources to families than almost any other nation: Hungary and Norway. Despite their programs, they have fertility rates of 1.5 and 1.4 children for every woman, respectively—far below the replacement rate of 2.1, the level needed to keep the population steady. The U.S. fertility rate is 1.6.

Demographers suggest the reluctance to have kids is a fundamental cultural shift rather than a purely financial one.

“I used to say to myself, I’m too young. I have to finish my bachelor’s degree. I have to find a partner. Then suddenly I woke up and I was 28 years old, married, with a car and a house and a flexible job and there were no more excuses,” said Norwegian Nancy Lystad Herz. “Even though there are now no practical barriers, I realised that I don’t want children.”

Both Hungary and Norway spend more than 3% of GDP on their different approaches to promoting families—more than the amount they spend on their militaries, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

Hungary says in recent years its spending on policies for families has exceeded 5% of GDP. The U.S. spends around 1% of GDP on family support through child tax credits and programs aimed at low-income Americans.

Hungary’s subsidised housing loan program has helped almost 250,000 families buy or upgrade their homes, the government says. Orsolya Kocsis, a 28-year-old working in human resources, knows having kids would help her and her husband buy a larger house in Budapest, but it isn’t enough to change her mind about not wanting children.

“If we were to say we’ll have two kids, we could basically buy a new house tomorrow,” she said. “But morally, I would not feel right having brought a life into this world to buy a house.”

Promoting baby-making, known as pro natalism, is a key plank of Prime Minister Viktor Orbán ’s broader populist agenda . Hungary’s biennial Budapest Demographic Summit has become a meeting ground for prominent conservative politicians and thinkers. Former Fox News anchor Tucker Carlson and JD Vance, Trump’s vice president pick, have lauded Orbán’s family policies.

Orbán portrays having children inside what he has called a “traditional” family model as a national duty, as well as an alternative to immigration for growing the population. The benefits for child-rearing in Hungary are mostly reserved for married, heterosexual, middle-class couples. Couples who divorce lose subsidised interest rates and in some cases have to pay back the support.

Hungary’s population, now less than 10 million, has been shrinking since the 1980s. The country is about the size of Indiana.

“Because there are so few of us, there’s always this fear that we are disappearing,” said Zsuzsanna Szelényi, program director at the CEU Democracy Institute and author of a book on Orbán.

Hungary’s fertility rate collapsed after the fall of the Soviet Union and by 2010 was down to 1.25 children for every woman. Orbán, a father of five, and his Fidesz party swept back into power that year after being ousted in the early 2000s. He expanded the family support system over the next decade.

Hungary’s fertility rate rose to 1.6 children for every woman in 2021. Ivett Szalma, an associate professor at Corvinus University of Budapest, said that like in many other countries, women in Hungary who had delayed having children after the global financial crisis were finally catching up.

Then progress stalled. Hungary’s fertility rate has fallen for the past two years. Around 51,500 babies have been born there this year through August, a 10% drop compared with the same period last year. Many Hungarian women cite underfunded public health and education systems and difficulties balancing work and family as part of their hesitation to have more children.

Anna Nagy, a 35-year-old former lawyer, had her son in January 2021. She received a loan of about $27,300 that she didn’t have to start paying back until he turned 3. Nagy had left her job before getting pregnant but still received government-funded maternity payments, equal to 70% of her former salary, for the first two years and a smaller amount for a third year.

She used to think she wanted two or three kids, but now only wants one. She is frustrated at the implication that demographic challenges are her responsibility to solve. Economists point to increased immigration and a higher retirement age as other offsets to the financial strains on government budgets from a declining population.

“It’s not our duty as Hungarian women to keep the nation alive,” she said.

Hungary is especially generous to families who have several children, or who give birth at younger ages. Last year, the government announced it would restrict the loan program used by Nagy to women under 30. Families who pledge to have three or more children can get more than $150,000 in subsidised loans. Other benefits include a lifetime exemption from personal taxes for mothers with four or more kids, and up to seven extra annual vacation days for both parents.

Under another program that’s now expired, nearly 30,000 families used a subsidy to buy a minivan, the government said.

Critics of Hungary’s family policies say the money is wasted on people who would have had large families anyway. The government has also been criticised for excluding groups such as the minority Roma population and poorer Hungarians. Bank accounts, credit histories and a steady employment history are required for many of the incentives.

Orbán’s press office didn’t respond to requests for comment. Tünde Fűrész, head of a government-backed demographic research institute, disagreed that the policies are exclusionary and said the loans were used more heavily in economically depressed areas.

Government programs weren’t a determining factor for Eszter Gerencsér, 37, who said she and her husband always wanted a big family. They have four children, ages 3 to 10.

They received about $62,800 in low-interest loans through government programs and $35,500 in grants. They used the money to buy and renovate a house outside of Budapest. After she had her fourth child, the government forgave $11,000 of the debt. Her family receives a monthly payment of about $40 a month for each child.

Most Hungarian women stay home with their children until they turn 2, after which maternity payments are reduced. Publicly run nurseries are free for large families like hers. Gerencsér worked on and off between her pregnancies and returned full-time to work, in a civil-service job, earlier this year.

She still thinks Hungarian society is stacked against mothers and said she struggled to find a job because employers worried she would have to take lots of time off.

The country’s international reputation as family-friendly is “what you call good marketing,” she said.

Norway has been incentivising births for decades with generous parental leave and subsidised child care. New parents in Norway can share nearly a year of fully paid leave, or around 14 months at 80% pay. More than three months are reserved for fathers to encourage more equal caregiving. Mothers are entitled to take at least an hour at work to breast-feed or pump.

The government’s goal has never been explicitly to encourage people to have more children, but instead to make it easier for women to balance careers and children, said Trude Lappegard, a professor who researches demography at the University of Oslo. Norway doesn’t restrict benefits for unmarried parents or same-sex couples.

Its fertility rate of 1.4 children per woman has steadily fallen from nearly 2 in 2009. Unlike Hungary, Norway’s population is still growing for now, due mostly to immigration.

“It is difficult to say why the population is having fewer children,” Kjersti Toppe, the Norwegian Minister of Children and Families, said in an email. She said the government has increased monthly payments for parents and has formed a committee to investigate the baby bust and ways to reverse it.

More women in Norway are childless or have only one kid. The percentage of 45-year-old women with three or more children fell to 27.5% last year from 33% in 2010. Women are also waiting longer to have children—the average age at which women had their first child reached 30.3 last year. The global surge in housing costs and a longer timeline for getting established in careers likely plays a role, researchers say. Older first-time mothers can face obstacles: Women 35 and older are at higher risk of infertility and pregnancy complications.

Gina Ekholt, 39, said the government’s policies have helped offset much of the costs of having a child and allowed her to maintain her career as a senior adviser at the nonprofit Save the Children Norway. She had her daughter at age 34 after a round of state-subsidised IVF that cost about $1,600. She wanted to have more children but can’t because of fertility issues.

She receives a monthly stipend of about $160 a month, almost fully offsetting a $190 monthly nursery fee.

“On the economy side, it hasn’t made a bump. What’s been difficult for me is trying to have another kid,” she said. “The notion that we should have more kids, and you’re very selfish if you have only had one…those are the things that took a toll on me.”

Her friend Ewa Sapieżyńska, a 44-year-old Polish-Norwegian writer and social scientist with one son, has helped her see the upside of the one-child lifestyle. “For me, the decision is not about money. It’s about my life,” she said.