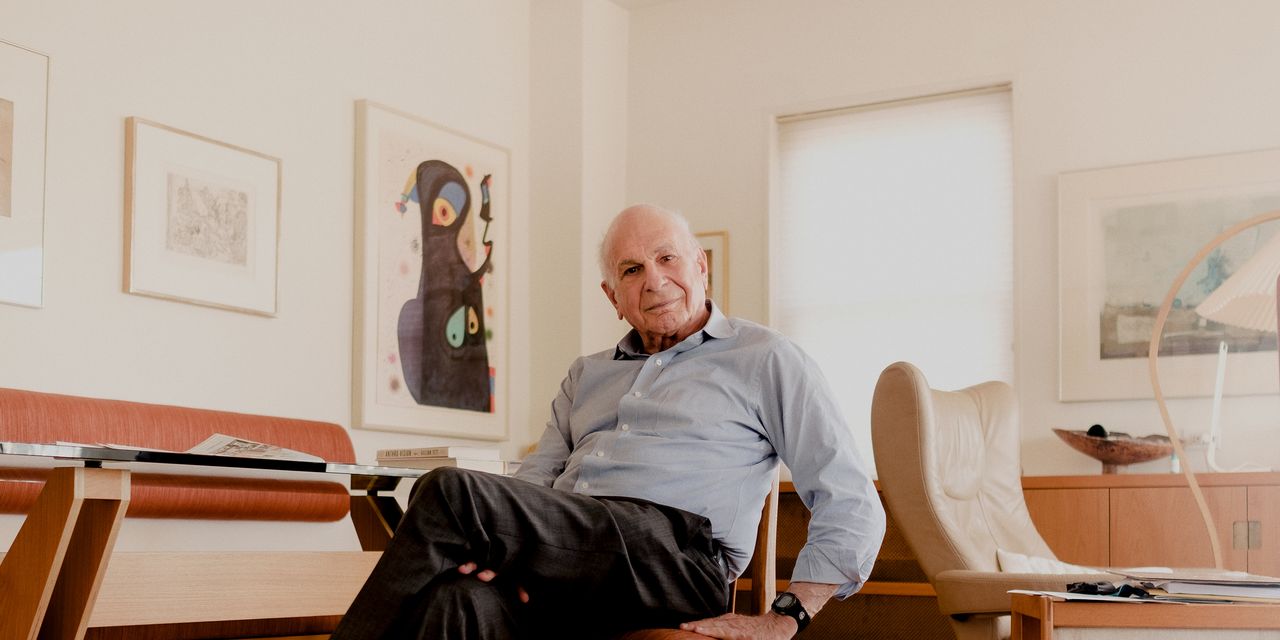

Daniel Kahneman explained investors to themselves.

A psychologist at Princeton University and winner of the Nobel Prize in economics, Kahneman died on March 27, age 90.

Before the pioneering work done by Kahneman and his research partner, Amos Tversky, who died in 1996, economists had assumed that people were “rational,” meaning we are self-interested, use all available information to make unbiased decisions, and our preferences are consistent.

Kahneman and Tversky showed that’s nonsense. Their findings, directly or indirectly, inspired change across the business world, including the redesign of organ-donation programs and improvements in planning for multibillion-dollar infrastructure projects .

Kahneman was a pioneer of what became known as behavioural economics, although he always saw himself as a psychologist. Investors who take Kahneman and Tversky’s lessons to heart can minimise fees, losses and regrets. Kahneman may well have had more influence on investing than anyone else who wasn’t a professional investor.

I first met Danny, as everyone called him, at a conference on behavioural economics in 1996. For years, as an investing journalist, I had wondered: Why are smart people so stupid about money?

About five minutes into Danny’s presentation, I realised he had the answers—not only to that question, but to nearly every mystery of financial behaviour.

Why do we sell our winners too soon and hang onto our losers too long? Why don’t we realize that most hot streaks are just luck? Why do we say we have a high tolerance for risk and then suffer the torments of the damned when the market falls? Why do we ignore the odds when we know they’re stacked against us?

Danny paced softly back and forth at the front of the room, his blue-green eyes sparkling with amusement as he documented these behaviours and demolished conventional economic theory.

For decades, he and Tversky had conducted experiments, almost childlike in their simplicity, to see how people really think and behave.

No, Danny said, money lost isn’t the same as money gained. Losses feel at least twice as painful as gains feel pleasant. He asked the conference attendees: If you’d lose $100 on a coin toss if it came up tails, how much would you have to win on heads before you’d take the bet? Most of us said $200 or more.

No, people don’t incorporate all available information. We think short streaks in a random process enable us to predict what comes next. We think jackpots happen more often than they do, making us overconfident. We think disasters are more common than they are, making us suckers for schemes that purport to protect us.

Ask people if they want to take a risk with an 80% chance of success, and most say yes. Ask instead if they’d incur the same risk with a 20% chance of failure, and many say no.

Noting that the stocks people sell outperform the ones they buy, Danny joked that “the cost of having an idea is 4%.”

I wasn’t just struck by his insights; I was stricken by them. I immediately bought all three of the books he had edited. For days, I sat in a windowless room, reading feverishly, red pen in hand, scribbling notes, underlining entire paragraphs, peppering the margins with arrows and exclamation points.

In 2001, a year before Danny won the Nobel, I wrote a long profile of him .

“The most important question to ask before making a decision,” he told me, “is ‘What is the base rate?’”

He meant you should begin every major decision by figuring out the objective odds of success, given the historical range of outcomes in similar situations.

If you’re thinking of starting a new business, your gut might tell you there’s no way you can fail. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, however, half of new businesses die within the first five years . That base rate comes from millions of startups, each of which also expected to succeed. You, on the other hand, are a sample of one.

Knowing that the base rate is 50/50 shouldn’t deter you from trying, but it should prevent you from being unrealistically optimistic.

Danny knew base rates weren’t quite everything. He told me that before he proposed to his second wife, Anne Treisman, he said to her: “I’m Jewish, you’re not. I’m neurotic, you’re not. Almost half of all marriages end in divorce. The base rates are against us.”

“Oh, who cares about base rates!” she replied. Their marriage lasted four decades; Treisman died in 2018.

In 1969, Danny was teaching at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem when he asked Tversky, a mathematical psychologist and colleague there, to visit his class.

In his guest lecture, Tversky argued humans aren’t that bad at estimating risks and probabilities.

“I just don’t believe it!” exclaimed Danny, who was studying visual perception. He already believed that just as optical illusions fool the eye, cognitive illusions fool the mind.

The two men continued their debate over lunch—and for many years after . Amos was organized, confident, quantitatively brilliant. Danny was untidy, self-doubting, astoundingly intuitive. Together, they were intellectual lightning in a bottle.

In 1971, to decide whose name would be listed as lead author on the first scientific paper they published together, the two men flipped a coin. Over the next quarter-century, they published more than two dozen papers together.

In 2006, Danny asked me to help him write a book . I auditioned for a few months, coming up with several different proposals for how to structure the project. We finally got started in early 2007.

What eventually emerged was “ Thinking, Fast and Slow ,” published late in 2011: an internationally bestselling memoir that also offered an encyclopaedic explanation of how the human mind works.

Early on, Danny took me to lunch with his wife near the Princeton campus. When he stepped away, I asked Anne, “Do you think Danny is crazy for wanting to do this book with me?”

“No,” she said. “But you might be crazy for wanting to do it with him.”

In the beginning, I wrote the first drafts of chapters that never saw the light of day. Gradually, Danny took over the writing, agonising over every sentence, as I rewrote and edited.

Late in 2007, as we were polishing the chapter called “The Illusion of Validity,” I woke up one night in an icy sweat, pulse racing, gasping for air. My wife rushed me to the emergency room. It turned out I hadn’t had a heart attack; I’d had a panic attack, the only one in my life before or since.

Danny was even more alarmed than I was.

In 2008 I moved on, joining The Wall Street Journal. Neither of us would ever publicly discuss our book divorce; Danny finished the final third of the book without me.

“Collaborations don’t always end well,” he’d warned me on our first day of work together, “so I want to make sure you will always think of me as a mensch,” a good person.

And so I do—the most complicated mensch I’ve ever known.

Working on the book exposed me to three of Danny’s qualities I hadn’t previously encountered in their full intensity. Only years later did I realise that I’ve internalised them as a journalist and an investor. Or so I hope.

First, Danny saw everything through a child’s eyes or, as some people call it, “beginner’s mind.” No one else I’ve ever known has so often asked: Why? Instead of assuming the status quo is valid, Danny always started by wondering whether it made any sense.

He was also relentlessly self-critical. I once showed him a letter I’d gotten from a reader telling me—correctly but rudely—that I was wrong about something. “Do you have any idea how lucky you are to have thousands of people who can tell you you’re wrong?” Danny said.

Finally, Danny could rework what we had already done as if it had never existed. Most people hate changing their mind; he liked nothing better, when the evidence justified it. “I have no sunk costs,” he would say.

One of his favourite words, while working on the book, was “miserable.” He used it to describe whatever we had just written; the process of writing a book; and, above all, himself.

Danny’s misery was largely rooted in the decades he and Amos had spent exploring the failings of the human mind by picking apart their own errors of thought and judgment.

Taking the outside view on everything else had given Danny the outside view on himself. He embodied the ultimate form of self-knowledge: to distrust yourself above all.

He knew full well how smart he was, but he also knew how foolish he could be. Noticing that he intuitively stereotyped a bespectacled child as “the young professor,” Danny realised people extrapolate the future from almost no data at all. After buying an expensive apartment, he laughed at knowing that he would also overpay to furnish it.

Born in 1934 in what today is Tel Aviv, Israel, while his mother was visiting there, Danny was raised in France. He spent much of his childhood hiding from the Nazis in barns and chicken coops in the French countryside.

He insisted that didn’t explain much about him; after all, not every survivor of the Holocaust had become a self-critical psychologist fascinated by financial behaviour.

Instead, he credited his success to hard work—but even more to luck, especially meeting Tversky.

Danny also insisted that studying the pitfalls and paradoxes of the human mind didn’t make him any better at problem-solving than anybody else: “I’m just better at recognising my mistakes after I make them.”

For all his knowledge of how foolish investors can be, Danny didn’t try to outsmart the market. “I don’t try to be clever at all,” he told me. Most of his money was in index funds. “The idea that I could see what no one else can is an illusion,” he said.

“All of us would be better investors,” he often said, “if we just made fewer decisions.”

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

What a quarter-million dollars gets you in the western capital.

Alexandre de Betak and his wife are focusing on their most personal project yet.

CIOs can take steps now to reduce risks associated with today’s IT landscape

As tech leaders race to bring Windows systems back online after Friday’s software update by cybersecurity company CrowdStrike crashed around 8.5 million machines worldwide, experts share with CIO Journal their takeaways for preparing for the next major information technology outage.

Be familiar with how vendors develop, test and release their software

IT leaders should hold vendors deeply integrated within IT systems, such as CrowdStrike , to a “very high standard” of development, release quality and assurance, said Neil MacDonald , a Gartner vice president.

“Any security vendor has a responsibility to do extensive regression testing on all versions of Windows before an update is rolled out,” he said.

That involves asking existing vendors to explain how they write software, what testing they do and whether customers may choose how quickly to roll out an update.

“Incidents like this remind all of us in the CIO community of the importance of ensuring availability, reliability and security by prioritizing guardrails such as deployment and testing procedures and practices,” said Amy Farrow, chief information officer of IT automation and security company Infoblox.

Re-evaluate how your firm accepts software updates from ‘trusted’ vendors

While automatically accepting software updates has become the norm—and a recommended security practice—the CrowdStrike outage is a reminder to take a pause, some CIOs said.

“We still should be doing the full testing of packages and upgrades and new features,” said Paul Davis, a field chief information security officer at software development platform maker JFrog . undefined undefined Though it’s not feasible to test every update, especially for as many as hundreds of software vendors, Davis said he makes it a priority to test software patches according to their potential severity and size.

Automation, and maybe even artificial intelligence-based IT tools, can help.

“Humans are not very good at catching errors in thousands of lines of code,” said Jack Hidary, chief executive of AI and quantum company SandboxAQ. “We need AI trained to look for the interdependence of new software updates with the existing stack of software.”

Develop a disaster recovery plan

An incident rendering Windows computers unusable is similar to a natural disaster with systems knocked offline, said Gartner’s MacDonald. That’s why businesses should consider natural disaster recovery plans for maintaining the resiliency of their operations.

One way to do that is to set up a “clean room,” or an environment isolated from other systems, to use to bring critical systems back online, according to Chirag Mehta, a cybersecurity analyst at Constellation Research.

Businesses should also hold tabletop exercises to simulate risk scenarios, including IT outages and potential cyber threats, Mehta said.

Companies that back up data regularly were likely less impacted by the CrowdStrike outage, according to Victor Zyamzin, chief business officer of security company Qrator Labs. “Another suggestion for companies, and we’ve been saying that again and again for decades, is that you should have some backup procedure applied, running and regularly tested,” he said.

Review vendor and insurance contracts

For any vendor with a significant impact on company operations , MacDonald said companies can review their contracts and look for clauses indicating the vendors must provide reliable and stable software.

“That’s where you may have an advantage to say, if an update causes an outage, is there a clause in the contract that would cover that?” he said.

If it doesn’t, tech leaders can aim to negotiate a discount serving as a form of compensation at renewal time, MacDonald added.

The outage also highlights the importance of insurance in providing companies with bottom-line protection against cyber risks, said Peter Halprin, a partner with law firm Haynes Boone focused on cyber insurance.

This coverage can include protection against business income losses, such as those associated with an outage, whether caused by the insured company or a service provider, Halprin said.

Weigh the advantages and disadvantages of the various platforms

The CrowdStrike update affected only devices running Microsoft Windows-based systems , prompting fresh questions over whether enterprises should rely on Windows computers.

CrowdStrike runs on Windows devices through access to the kernel, the part of an operating system containing a computer’s core functions. That’s not the same for Apple ’s Mac operating system and Linux, which don’t allow the same level of access, said Mehta.

Some businesses have converted to Chromebooks , simple laptops developed by Alphabet -owned Google that run on the Chrome operating system . “Not all of them require deeper access to things,” Mehta said. “What are you doing on your laptop that actually requires Windows?”