Alexa Is in Millions of Households—and Amazon Is Losing Billions

Company’s strategy to set prices low for Echo speakers and other smart devices, expecting them to generate income elsewhere in the tech giant, hasn’t paid off

Company’s strategy to set prices low for Echo speakers and other smart devices, expecting them to generate income elsewhere in the tech giant, hasn’t paid off

Amazon.com ’s Echo speakers are the type of business success companies don’t want: a widely purchased product that is also a giant money loser.

Chief Executive Andy Jassy is trying to plug that hole—and move away from the Amazon accounting tactic that helped create it.

When Amazon launched the Echo smart home devices with its Alexa voice assistant in 2014, it pulled a page from shaving giant Gillette’s classic playbook: sell the razors for a pittance in the hope of making heaps of money on purchases of the refill blades.

A decade later, the payoff for Echo hasn’t arrived. While hundreds of millions of customers have Alexa-enabled devices, the idea that people would spend meaningful amounts of money to buy goods on Amazon by talking to the iconic voice assistant on the underpriced speakers didn’t take off.

Customers actually used Echo mostly for free apps such as setting alarms and checking the weather. “We worried we’ve hired 10,000 people and we’ve built a smart timer,” said a former senior employee.

As a result, Amazon has lost tens of billions of dollars on its devices business, which includes Echos and other products such as Kindles , Fire TV Sticks and video doorbells, according to internal documents and people familiar with the business.

Between 2017 and 2021, Amazon had more than $25 billion in losses from its devices business, according to the documents. The losses for the years before and after that period couldn’t be determined.

It is a high-stakes miscalculation the tech giant made under founder Jeff Bezos that current CEO Jassy, who took the helm in 2021 , is now trying to change. As part of a plan to reverse losses, Amazon is launching a paid tier of Alexa as soon as this month, a move even some engineers working on the project worry won’t work, according to people familiar with those efforts.

An Amazon spokeswoman said the devices division has established numerous profitable businesses and is well-positioned to continue doing so, adding: “Hundreds of millions of Amazon devices are used by customers around the world, and to us, there is no greater measure of success.” The company declined to make Jassy or Panos Panay, who leads devices, available for an interview.

As Jassy tries to fix it, he is rethinking the obscure Bezos-era metric inside Amazon that helps explain why Echo and other devices could accrue such huge losses for so long with little repercussion. Called “downstream impact,” or DSI, it assigns a financial value to a product or a service based on how customers spend within Amazon’s ecosystem after they buy it.

Downstream impact has been used across Amazon business lines, from its Prime membership program to its video offerings and music.

The metric was developed in 2011 by a team of economists including an eventual Nobel Prize winner. In some instances, the model worked clearly. When customers buy Amazon’s Kindle e-reader—one of Amazon’s profitable devices—they are very likely to then buy ebooks to read on that device. Ebooks are part of the books business, not the devices business, but Amazon leaders said it made sense for the Kindle team to claim part of revenue when assessing their product’s internal value.

Similarly, some revenue from advertisements displayed on Fire TV streaming devices is also claimed as Fire TV revenue.

Some Amazon devices can count on direct revenue, such as by selling users subscriptions attached to the product. More than half of customers who buy smart-camera doorbells from Ring, another profitable Amazon device that the company bought in 2018, purchase security subscriptions.

In other cases—especially Echo devices—the downstream impact idea broke down, said the people familiar with the devices business.

Unlike the revenue, operating profit and other financial metrics Amazon and other companies report publicly, downstream impact is an estimate used internally, and not a particularly scientific or precise one.

Echo and other devices are generally sold at or below the cost to make them. The devices team, in internal pitch meetings to senior management, would claim the top end of a range of estimated revenue from downstream impact, some of the people said. The team relied heavily on the metric to justify costs related to Echo and other devices and the growing size of staff devoted to the business, which at one point swelled to more than 15,000 employees across all its products.

The system also enabled divisions to count the same revenue more than once, according to former executives. For example, if a customer bought an Echo device and Amazon’s Fire TV streaming stick, and then signed up for Amazon Prime, both the Echo team and the Fire TV team could claim cuts of the revenue from the Prime subscription.

Other downstream impact revenue that helped Echo devices look financially better on paper internally came from Amazon Music, a Spotify competitor with a $10 monthly subscription version.

The devices team also claimed a piece of shopping revenue, because people can use Alexa to order or reorder goods—though former employees on the Alexa shopping team say that doesn’t contribute meaningful e-commerce revenue.

The Amazon spokeswoman said more than half of Echo owners have used it to shop but declined to answer questions on how much they buy or how often they do so.

“Basically DSI was the golden thing that kept us all afloat all these years,” said a former longtime Amazon employee who worked on Echo.

Amazon’s devices operation was a pet project of Bezos, and the Alexa voice assistant and the Echo speakers through which it communicated were inspired by his interest in the spaceship computer in “Star Trek.”

“When launching products back then, we didn’t have to have a profit timeline for them,” said a former longtime devices executive. “We had to get the system in people’s homes and we’d win. Innovate, and then figure out how to make money later.”

To do that, the team had to keep prices low. Amazon sometimes even gave away versions of the smart speaker as part of promotions in a bid to get a larger base of users.

“We don’t have to make money when we sell you the device,” former Amazon devices senior vice president Dave Limp told The Wall Street Journal in 2019. “Instead, we make money when people actually use the device.”

Amazon was up against competition from giant rivals including Google, whose line of smart speakers was priced very low. Both companies were trying to grab space in as many homes as possible. “We were constantly checking their pricing. There would be water cooler talk like ‘what are we trying to [do], race Google to the bottom?’” said a former person on the Echo team.

Bezos protected the devices team, even as losses mounted, said people familiar with the unit, continuing investment and expanding staffing.

In 2018, devices lost more than $5 billion. It was spending lavishly to develop devices such as an in-home robot eventually named Astro that could act as a smart butler. Unveiled in 2021 but still sold only by invitation, Astro boasts a $1,600 price tag and more than $1 billion in total development costs. This month, Amazon killed off its Astro for Business product.

An Amazon spokeswoman denied Bezos shielded the devices business or treated it any differently than Amazon’s other businesses.

Despite Bezos’ well-known mantra to take risks and “fail fast,” the losses racked up over years. Customers weren’t shopping on the device, and attempts to sell services such as security through Alexa also floundered. Pushing advertisements through the smart speakers bothered users, so Amazon limited their use.

In 2019, device losses increased to more than $6 billion, according to internal documents. Still, the device team introduced new products, such as the Luna gaming streaming service with corresponding devices and the Halo fitness tracker.

Jassy, who had headed Amazon’s lucrative cloud-computing business before becoming CEO, has a reputation as an operator laser-focused on profits.

Soon after taking the reins from Bezos three years ago, he did a profitability review of Amazon’s business lines, from retail and logistics to advertising. He zeroed in on the money-losing devices business , the Journal has reported.

Teams working on new devices without a clear path to profitability were disbanded. Those working on more mature products that weren’t showing revenue or profits were instructed to develop revenue streams. Jassy often asked leaders to demonstrate a path to profitability without using downstream impact as a crutch, according to people familiar with the discussions.

In October 2022, Amazon killed off Amazon Glow, a video-calling gadget that was losing money on each sale—and wasn’t recouping the losses when customers used it or paid a fee for content. The product had launched only a year earlier. Jassy had told the team that he wanted it to be profitable before downstream impact.

The Amazon spokeswoman said the company plans to continue measuring the success of its businesses in part by how they help other parts of the company grow.

In late 2022, Amazon’s senior team put plans in place to begin laying off corporate employees in order to shore up profits across Amazon. Devices were a focus of the cuts.

More devices were shut down last year, including the Halo, Amazon’s fitness wearable. In late 2023, Limp, the Amazon devices head, left Amazon after more than 13 years at the company. He said in a note to employees that “It’s not because I am less bullish about the devices and services business.”

Jassy’s team also zeroed in on Alexa and the Echo device. While the technology behind Echo is wildly popular—there are more than 500 million Alexa-enabled devices globally—Jassy urged the teams to find ways to monetize the device and its technology.

A group was assembled under Amazon vice president Heather Zorn to create a way to charge customers a fee for Alexa. Code-named “Banyan,” like the tree, the group has been working to create a product called “Remarkable Alexa,” that would be built on an entirely new technology stack and have more capabilities than the current version of Alexa installed on Amazon devices, according to people familiar with the matter. Business Insider previously reported some details about Remarkable Alexa.

The new technology would more seamlessly allow users to control functions like smart home devices using their voices rather than opening an app. It will also incorporate generative artificial intelligence more than the current Echo experience. Bezos hinted at a new version of Alexa in a podcast interview in December. “Alexa is about to get a lot smarter,” he told the host.

Zorn’s team is slated to launch the new Alexa subscription service as soon as this month, and the team is still figuring out what it should charge, according to one of the people.

One person who worked on the team said some members were skeptical about whether customers would want to pay for yet another subscription in an age of cord-cutting, since people already pay a la carte for subscriptions such as Netflix, Spotify and even Amazon’s own services Prime and Amazon Music. The person also said some members worried that the new Alexa didn’t offer a compelling enough product worth paying for.

“The technology isn’t there, but they have a deadline” to launch the product, the person said.

The Amazon spokeswoman said that Amazon is closer than ever to building the world’s best personal assistant and that the opportunity is greater than what would appear on a balance sheet.

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

What a quarter-million dollars gets you in the western capital.

Alexandre de Betak and his wife are focusing on their most personal project yet.

Subsidised minivans, no income taxes: Countries have rolled out a range of benefits to encourage bigger families, with no luck

Imagine if having children came with more than $150,000 in cheap loans, a subsidised minivan and a lifetime exemption from income taxes.

Would people have more kids? The answer, it seems, is no.

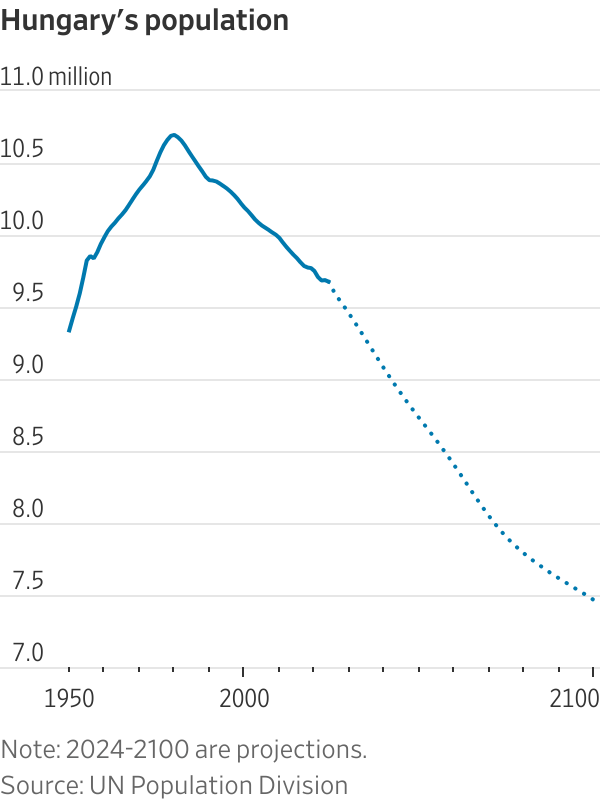

These are among the benefits—along with cheap child care, extra vacation and free fertility treatments—that have been doled out to parents in different parts of Europe, a region at the forefront of the worldwide baby shortage. Europe’s overall population shrank during the pandemic and is on track to contract by about 40 million by 2050, according to United Nations statistics.

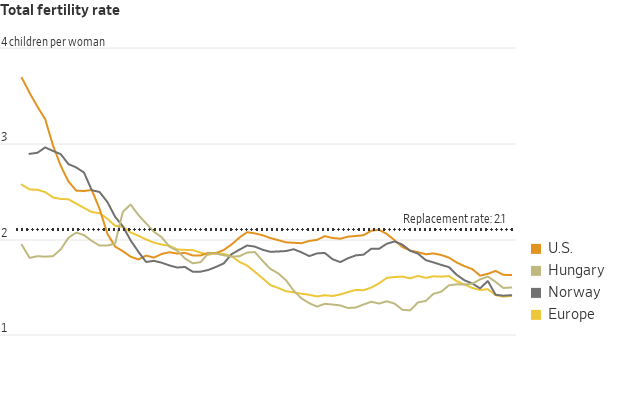

Birthrates have been falling across the developed world since the 1960s. But the decline hit Europe harder and faster than demographers expected—a foreshadowing of the sudden drop in the U.S. fertility rate in recent years.

Reversing the decline in birthrates has become a national priority among governments worldwide, including in China and Russia , where Vladimir Putin declared 2024 “the year of the family.” In the U.S., both Kamala Harris and Donald Trump have pledged to rethink the U.S.’s family policies . Harris wants to offer a $6,000 baby bonus. Trump has floated free in vitro fertilisation and tax deductions for parents.

Europe and other demographically challenged economies in Asia such as South Korea and Singapore have been pushing back against the demographic tide with lavish parental benefits for a generation. Yet falling fertility has persisted among nearly all age groups, incomes and education levels. Those who have many children often say they would have them even without the benefits. Those who don’t say the benefits don’t make enough of a difference.

Two European countries devote more resources to families than almost any other nation: Hungary and Norway. Despite their programs, they have fertility rates of 1.5 and 1.4 children for every woman, respectively—far below the replacement rate of 2.1, the level needed to keep the population steady. The U.S. fertility rate is 1.6.

Demographers suggest the reluctance to have kids is a fundamental cultural shift rather than a purely financial one.

“I used to say to myself, I’m too young. I have to finish my bachelor’s degree. I have to find a partner. Then suddenly I woke up and I was 28 years old, married, with a car and a house and a flexible job and there were no more excuses,” said Norwegian Nancy Lystad Herz. “Even though there are now no practical barriers, I realised that I don’t want children.”

Both Hungary and Norway spend more than 3% of GDP on their different approaches to promoting families—more than the amount they spend on their militaries, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

Hungary says in recent years its spending on policies for families has exceeded 5% of GDP. The U.S. spends around 1% of GDP on family support through child tax credits and programs aimed at low-income Americans.

Hungary’s subsidised housing loan program has helped almost 250,000 families buy or upgrade their homes, the government says. Orsolya Kocsis, a 28-year-old working in human resources, knows having kids would help her and her husband buy a larger house in Budapest, but it isn’t enough to change her mind about not wanting children.

“If we were to say we’ll have two kids, we could basically buy a new house tomorrow,” she said. “But morally, I would not feel right having brought a life into this world to buy a house.”

Promoting baby-making, known as pro natalism, is a key plank of Prime Minister Viktor Orbán ’s broader populist agenda . Hungary’s biennial Budapest Demographic Summit has become a meeting ground for prominent conservative politicians and thinkers. Former Fox News anchor Tucker Carlson and JD Vance, Trump’s vice president pick, have lauded Orbán’s family policies.

Orbán portrays having children inside what he has called a “traditional” family model as a national duty, as well as an alternative to immigration for growing the population. The benefits for child-rearing in Hungary are mostly reserved for married, heterosexual, middle-class couples. Couples who divorce lose subsidised interest rates and in some cases have to pay back the support.

Hungary’s population, now less than 10 million, has been shrinking since the 1980s. The country is about the size of Indiana.

“Because there are so few of us, there’s always this fear that we are disappearing,” said Zsuzsanna Szelényi, program director at the CEU Democracy Institute and author of a book on Orbán.

Hungary’s fertility rate collapsed after the fall of the Soviet Union and by 2010 was down to 1.25 children for every woman. Orbán, a father of five, and his Fidesz party swept back into power that year after being ousted in the early 2000s. He expanded the family support system over the next decade.

Hungary’s fertility rate rose to 1.6 children for every woman in 2021. Ivett Szalma, an associate professor at Corvinus University of Budapest, said that like in many other countries, women in Hungary who had delayed having children after the global financial crisis were finally catching up.

Then progress stalled. Hungary’s fertility rate has fallen for the past two years. Around 51,500 babies have been born there this year through August, a 10% drop compared with the same period last year. Many Hungarian women cite underfunded public health and education systems and difficulties balancing work and family as part of their hesitation to have more children.

Anna Nagy, a 35-year-old former lawyer, had her son in January 2021. She received a loan of about $27,300 that she didn’t have to start paying back until he turned 3. Nagy had left her job before getting pregnant but still received government-funded maternity payments, equal to 70% of her former salary, for the first two years and a smaller amount for a third year.

She used to think she wanted two or three kids, but now only wants one. She is frustrated at the implication that demographic challenges are her responsibility to solve. Economists point to increased immigration and a higher retirement age as other offsets to the financial strains on government budgets from a declining population.

“It’s not our duty as Hungarian women to keep the nation alive,” she said.

Hungary is especially generous to families who have several children, or who give birth at younger ages. Last year, the government announced it would restrict the loan program used by Nagy to women under 30. Families who pledge to have three or more children can get more than $150,000 in subsidised loans. Other benefits include a lifetime exemption from personal taxes for mothers with four or more kids, and up to seven extra annual vacation days for both parents.

Under another program that’s now expired, nearly 30,000 families used a subsidy to buy a minivan, the government said.

Critics of Hungary’s family policies say the money is wasted on people who would have had large families anyway. The government has also been criticised for excluding groups such as the minority Roma population and poorer Hungarians. Bank accounts, credit histories and a steady employment history are required for many of the incentives.

Orbán’s press office didn’t respond to requests for comment. Tünde Fűrész, head of a government-backed demographic research institute, disagreed that the policies are exclusionary and said the loans were used more heavily in economically depressed areas.

Government programs weren’t a determining factor for Eszter Gerencsér, 37, who said she and her husband always wanted a big family. They have four children, ages 3 to 10.

They received about $62,800 in low-interest loans through government programs and $35,500 in grants. They used the money to buy and renovate a house outside of Budapest. After she had her fourth child, the government forgave $11,000 of the debt. Her family receives a monthly payment of about $40 a month for each child.

Most Hungarian women stay home with their children until they turn 2, after which maternity payments are reduced. Publicly run nurseries are free for large families like hers. Gerencsér worked on and off between her pregnancies and returned full-time to work, in a civil-service job, earlier this year.

She still thinks Hungarian society is stacked against mothers and said she struggled to find a job because employers worried she would have to take lots of time off.

The country’s international reputation as family-friendly is “what you call good marketing,” she said.

Norway has been incentivising births for decades with generous parental leave and subsidised child care. New parents in Norway can share nearly a year of fully paid leave, or around 14 months at 80% pay. More than three months are reserved for fathers to encourage more equal caregiving. Mothers are entitled to take at least an hour at work to breast-feed or pump.

The government’s goal has never been explicitly to encourage people to have more children, but instead to make it easier for women to balance careers and children, said Trude Lappegard, a professor who researches demography at the University of Oslo. Norway doesn’t restrict benefits for unmarried parents or same-sex couples.

Its fertility rate of 1.4 children per woman has steadily fallen from nearly 2 in 2009. Unlike Hungary, Norway’s population is still growing for now, due mostly to immigration.

“It is difficult to say why the population is having fewer children,” Kjersti Toppe, the Norwegian Minister of Children and Families, said in an email. She said the government has increased monthly payments for parents and has formed a committee to investigate the baby bust and ways to reverse it.

More women in Norway are childless or have only one kid. The percentage of 45-year-old women with three or more children fell to 27.5% last year from 33% in 2010. Women are also waiting longer to have children—the average age at which women had their first child reached 30.3 last year. The global surge in housing costs and a longer timeline for getting established in careers likely plays a role, researchers say. Older first-time mothers can face obstacles: Women 35 and older are at higher risk of infertility and pregnancy complications.

Gina Ekholt, 39, said the government’s policies have helped offset much of the costs of having a child and allowed her to maintain her career as a senior adviser at the nonprofit Save the Children Norway. She had her daughter at age 34 after a round of state-subsidised IVF that cost about $1,600. She wanted to have more children but can’t because of fertility issues.

She receives a monthly stipend of about $160 a month, almost fully offsetting a $190 monthly nursery fee.

“On the economy side, it hasn’t made a bump. What’s been difficult for me is trying to have another kid,” she said. “The notion that we should have more kids, and you’re very selfish if you have only had one…those are the things that took a toll on me.”

Her friend Ewa Sapieżyńska, a 44-year-old Polish-Norwegian writer and social scientist with one son, has helped her see the upside of the one-child lifestyle. “For me, the decision is not about money. It’s about my life,” she said.