Landing a Job Is All About Who You Know (Again)

Networking is making a comeback as employers drown in computer-generated job applications

Networking is making a comeback as employers drown in computer-generated job applications

Nine-hundred eighty-three people applied online for a job posted recently by tech recruiter Rob Tansey. The candidate who got the offer wasn’t one of them.

Tansey, who scouts potential hires for aviation-software maker Veryon, received a half dozen referrals from a woman he knew from past job searches. One of those six quickly became the front-runner. That’s often how Tansey operates: He estimates that just 40% of successful applicants come in cold through his company’s job portal.

“There’s an idealist in me that wants to look at all the résumés,” he says. “The reality is you just can’t.”

Who-you-know networking is back. As the number of job applicants has swelled in recent years, the key to landing a new position often turns on a personal connection that can pluck your résumé out of online obscurity and ensure it’s seen by a real person.

Behind the resurgence: frustration with the digital slog that bogs down U.S. hiring. Many hiring managers and applicants agree that the ease with which job hunters can respond to help-wanted postings has broken the online-application process by creating high volumes of candidates that hiring managers can’t hope to parse through. Meanwhile, applicants say automatic screening tools are shutting them out of opportunities.

Reverting to referrals threatens to undermine corporate diversity efforts, which were supposed to be aided by online applications. Software promised to democratise hiring by reducing human biases, but wider talent pipelines have overwhelmed some employers to the point where they’re reaching for what’s worked in the past.

To promote the use of connections, some employers, like software giant Dassault Systemes , have increased cash rewards for employees whose recommendations lead to hires. Others, including the University of Miami and its health system with 20,000 total employees, have launched new referral-bonus programs. Corporate hiring software can allow companies to identify referred candidates first, boosting those applicants over the competition.

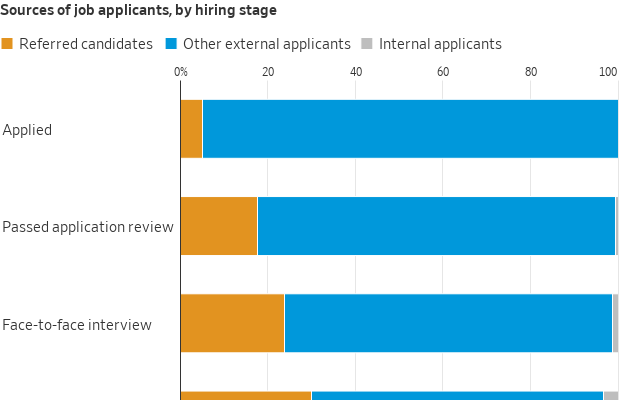

Whether recommendations come from in-house or outside the company, the advantages are significant, according to data compiled by the hiring-software company Greenhouse. For roles that were posted on Greenhouse job boards and filled in the first quarter of this year, applicants with referrals had a 50% chance of advancing past an initial résumé review, compared with 12% odds for other external candidates.

Thirty percent of eventual hires had referrals, even though people with referrals represented just 5% of the applicant pool.

“Candidates are so desperate to get noticed, and they’re asking, ‘What’s the cheat code? What’s the way to get through the filters?’” says Jon Stross, Greenhouse’s co-founder. “Get referred. It really increases your chances of getting through the first filter.”

The renewed reliance on networking comes as applicants and hiring managers are struggling to navigate the software that now dominates recruiting.

Companies are swamped by applicants in part because many job seekers are newly relying on ChatGPT and automated bots to fire off large volumes of résumés, or using other shortcuts like LinkedIn’s “easy apply” button.

Some human-resources professionals lament that cover letters sound eerily similar, as if written by the same nonhuman.

Candidates fume when they click “submit” and don’t hear back—and sometimes even when they do. Amanda Palasciano, in Red Bank, N.J., scored an interview for a senior copy-manager position as she sought a job in advertising. The catch was that her interviewer was an avatar, not a person.

The video call was awkward. Palasciano, 42, had a short window to record her response to each question. She didn’t know where to look. Soon after, she was rejected.

“It put a bad taste in my mouth about the company,” she says. “If that’s how much reliance you put on brand-new tools over people, this isn’t the right place for me.”

She decided to stop applying online and started asking former colleagues about short-term openings , aiming to convert one to a full-time job.

“This front door is locked,” Palasciano says. “We’re going through the back door, or we’re not working.”

Lindsay Broveleit, a Minneapolis-area vice president at the marketing agency Matato, didn’t bother posting a job listing online when she needed to fill a midlevel role this spring.

She feared that listing the position on LinkedIn or the company’s website would bring throngs of low-quality applications—and she was anxious about how truthful AI-enhanced applications might be.

“A couple of years ago, I would have absolutely pursued more digital channels that are more public-facing,” she says. Not now. “We don’t want that many applicants. We want good ones.”

She thought to tap her and her colleagues’ networks to fill the role, but she soon reconsidered—even those personal channels have become oversaturated with first- and second-degree connections looking for work.

Employees are “inundated with people asking for their help to navigate into open positions,” she says.

She contracted a staffing agency instead.

Whether using agencies or their own employees, more companies are turning to people to vet prospects.

Laserfiche, a maker of content-management software, has a longstanding employee-referral program and a renewed commitment to contact everyone who is recommended by an employee.

The guaranteed outreach does not ensure an offer, says Vice President of People Jenny Bode, but it is a chance for candidates with unconventional backgrounds to make a case for themselves. With about 400 applicants for a typical opening, that’s an opportunity not afforded to everyone.

Bode values referrals partly because one helped bring her to Laserfiche in 2022. She wasn’t even looking for a job when she heard from a former co-worker she’d kept in touch with.

“She reached out to me and said, ‘I have this position. Do you want to interview for it?’” Bode recalls.

Alison Mincey introduced referral bonuses of up to $2,500 when she became chief human resources officer at the University of Miami in 2022. She estimates one in 10 hires now starts with an employee referral. The program, she says, also helps with retention: Employees are more engaged when their input is valued, and newcomers are more likely to stay and thrive when they already know a co-worker.

On Greenhouse’s platform, when employees submit referrals, the software prompts them to “consider referring people from underrepresented backgrounds.”

That can be a challenge. People tend to know—and therefore recommend—people like themselves, says Ruth Thomas, chief of research and insights at PayScale, a compensation-management firm. (PayScale itself has lately doubled its usual share of new hires found through referrals, to 30%.)

Referral networks tend to reinforce demographic imbalances . A PayScale survey of 53,000 workers found that white men land more jobs and bigger raises through referrals than others because they are more likely to be connected to corporate decision makers.

Hiring managers might say, “They were in my club at Princeton, and therefore, they’re a good person,” says John Horton, an associate professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Sloan School of Management and co-author of a recent paper on artificial intelligence in hiring. “If people start to retreat away from an open market, and it happens much through who you know and references, that would be bad.”

Cisco Systems is leaning more heavily on referrals for hiring than it has in the past. But the network-equipment company knows the approach can run counter to diversity efforts, so it also launched an effort to hire more people of color and workers without four-year degrees, says Macy Andrews, vice president of employer branding for people and purpose. That hiring initiative looks to identify candidates with transferable skills rather than mandating college. Cisco so far has made over 100 hires through the initiative.

The company is looking to cut through the online-application morass in other ways as well. Cisco recruiters now visit college campuses with preprinted offer letters, so they can snap up students who make strong impressions.

“There is a bigger point here, which is that the process of sending in résumés and having thousands—sometimes millions—to go through isn’t the wave of the future,” she says.

Samuel Joynson, of Venice, Fla., launched a thoroughly modern job hunt after he lost his job when his company went through a reorganisation. He enlisted ChatGPT to edit his résumé and draft emails and cover letters.

The language didn’t sound like him—so he changed his approach.

Joynson, 28 years old, switched to writing his own letters and emails, investing about two hours into each application. He also pushed himself to contact everyone he knew at major tech companies including Apple, Google and Microsoft , where he talked to a friend from college. On calls, he asked them about their experiences at the companies, the office environment and remote-work policies.

“I took the approach of making it as human-based as possible,” he says.

Joynson’s old-fashioned strategy paid off. Many conversations led to introductions to other employees within his target companies. He landed a role and started as a senior technical program manager at Microsoft in April.

Francisco Denis recently discovered that connections—or lack thereof—can make all the difference. He says he was a finalist for a project-manager role at Disney but was told by a recruiter that the company decided to hire someone who had worked there in the past and could plug in immediately.

Denis, 40, has applied online for more than 100 jobs this year after moving on from an unsuccessful startup. His efforts have yielded only a handful of interviews, a jarring turn from a couple of years ago, when he was routinely headhunted. He’s pouring energy into networking for the first time in his career, reconnecting with former co-workers at companies he’d like to join. He often shares his résumé and describes his arduous job search to show that he’s not looking for a handout.

Still, even a system that relies on human connections can be gamed. On Fishbowl, an app for workplace venting and career advice, users have started a forum dubbed “Job Referrals!” It has drawn hundreds of thousands of members seeking endorsements from people they don’t know.

“Anyone willing to provide a referral to Amazon ?” one user posted.

In lieu of a handshake or business card, another offered an emoji: “Looking for a referral for Spotify, thanks in advance :).”

Bogus referrals could be win-wins for the people who give and receive them. The applicants gain an edge and, if they’re hired, their sponsors might be entitled to referral bonuses.

The companies that extended the offer? They’re left with one more hiring strategy that can’t be trusted.

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

What a quarter-million dollars gets you in the western capital.

Alexandre de Betak and his wife are focusing on their most personal project yet.

As Paris makes its final preparations for the Olympic games, its residents are busy with their own—packing their suitcases, confirming their reservations, and getting out of town.

Worried about the hordes of crowds and overall chaos the Olympics could bring, Parisians are fleeing the city in droves and inundating resort cities around the country. Hotels and holiday rentals in some of France’s most popular vacation destinations—from the French Riviera in the south to the beaches of Normandy in the north—say they are expecting massive crowds this year in advance of the Olympics. The games will run from July 26-Aug. 1.

“It’s already a major holiday season for us, and beyond that, we have the Olympics,” says Stéphane Personeni, general manager of the Lily of the Valley hotel in Saint Tropez. “People began booking early this year.”

Personeni’s hotel typically has no issues filling its rooms each summer—by May of each year, the luxury hotel typically finds itself completely booked out for the months of July and August. But this year, the 53-room hotel began filling up for summer reservations in February.

“We told our regular guests that everything—hotels, apartments, villas—are going to be hard to find this summer,” Personeni says. His neighbours around Saint Tropez say they’re similarly booked up.

As of March, the online marketplace Gens de Confiance (“Trusted People”), saw a 50% increase in reservations from Parisians seeking vacation rentals outside the capital during the Olympics.

Already, August is a popular vacation time for the French. With a minimum of five weeks of vacation mandated by law, many decide to take the entire month off, renting out villas in beachside destinations for longer periods.

But beyond the typical August travel, the Olympics are having a real impact, says Bertille Marchal, a spokesperson for Gens de Confiance.

“We’ve seen nearly three times more reservations for the dates of the Olympics than the following two weeks,” Marchal says. “The increase is definitely linked to the Olympic Games.”

According to the site, the most sought-out vacation destinations are Morbihan and Loire-Atlantique, a seaside region in the northwest; le Var, a coastal area within the southeast of France along the Côte d’Azur; and the island of Corsica in the Mediterranean.

Meanwhile, the Olympics haven’t necessarily been a boon to foreign tourism in the country. Many tourists who might have otherwise come to France are avoiding it this year in favour of other European capitals. In Paris, demand for stays at high-end hotels has collapsed, with bookings down 50% in July compared to last year, according to UMIH Prestige, which represents hotels charging at least €800 ($865) a night for rooms.

Earlier this year, high-end restaurants and concierges said the Olympics might even be an opportunity to score a hard-get-seat at the city’s fine dining.

In the Occitanie region in southwest France, the overall number of reservations this summer hasn’t changed much from last year, says Vincent Gare, president of the regional tourism committee there.

“But looking further at the numbers, we do see an increase in the clientele coming from the Paris region,” Gare told Le Figaro, noting that the increase in reservations has fallen directly on the dates of the Olympic games.

Michel Barré, a retiree living in Paris’s Le Marais neighbourhood, is one of those opting for the beach rather than the opening ceremony. In January, he booked a stay in Normandy for two weeks.

“Even though it’s a major European capital, Paris is still a small city—it’s a massive effort to host all of these events,” Barré says. “The Olympics are going to be a mess.”

More than anything, he just wants some calm after an event-filled summer in Paris, which just before the Olympics experienced the drama of a snap election called by Macron.

“It’s been a hectic summer here,” he says.

Parisians—Barré included—feel that the city, by over-catering to its tourists, is driving out many residents.

Parts of the Seine—usually one of the most popular summertime hangout spots —have been closed off for weeks as the city installs bleachers and Olympics signage. In certain neighbourhoods, residents will need to scan a QR code with police to access their own apartments. And from the Olympics to Sept. 8, Paris is nearly doubling the price of transit tickets from €2.15 to €4 per ride.

The city’s clear willingness to capitalise on its tourists has motivated some residents to do the same. In March, the number of active Airbnb listings in Paris reached an all-time high as hosts rushed to list their apartments. Listings grew 40% from the same time last year, according to the company.

With their regular clients taking off, Parisian restaurants and merchants are complaining that business is down.

“Are there any Parisians left in Paris?” Alaine Fontaine, president of the restaurant industry association, told the radio station Franceinfo on Sunday. “For the last three weeks, there haven’t been any here.”

Still, for all the talk of those leaving, there are plenty who have decided to stick around.

Jay Swanson, an American expat and YouTuber, can’t imagine leaving during the Olympics—he secured his tickets to see ping pong and volleyball last year. He’s also less concerned about the crowds and road closures than others, having just put together a series of videos explaining how to navigate Paris during the games.

“It’s been 100 years since the Games came to Paris; when else will we get a chance to host the world like this?” Swanson says. “So many Parisians are leaving and tourism is down, so not only will it be quiet but the only people left will be here for a party.”