The impetus for Judy Taylor to start her luxury handbag and jewellery resale company Madison Avenue Couture dates back to her career in investment banking more than two decades ago. At the time, she was an avid shopper for high-end clothing and had built a sizeable collection of corporate wear from designer labels.

Taylor eventually took an extended break from banking to travel the world and decided to sell the clothing on eBay.

“I was surprised at the money I netted by selling these used items and realized the potential of the online resale market,” Taylor says. “Not being someone to let an opportunity pass, I began to buy and sell new and almost new luxury clothing, shoes and handbags and saw how much they were in demand.”

Courtesy of Madison Avenue Couture

Her homespun venture quickly grew into a full-fledged profitable business, and in 2010, she established Madison Avenue Couture. Today, the brand bills itself to be the largest online independent reseller of new and never-worn Hermès holy grail bags, primarily Birkins and Kellys that are nearly impossible to find. It also sells a selection of pre-owned collectible and vintage Hermès, Chanel, Goyard, and Louis Vuitton bags, Hermès and Chanel jewellery, and accessories and sought-after fine jewellery.

Taylor says that her company enables any consumer with the means to buy highly in-demand goods.

“You can’t just go into Hermès and buy a Birkin because there usually aren’t any available, and if they are, customers are limited to buying two bags a year,” she says. “Chanel has also limited purchases since Covid, and other brands have imposed restrictions.”

According to Taylor, these tactics have increased market demand and have enabled luxury labels to increase their prices. However, since supply cannot meet demand, consumers are increasingly reaching out to the resale market, including her company, for these items.

“Our business continues to grow, and we have an extensive network to source handbags and jewellery,” Taylor says. “Unlike much of the traditional resale market, our items are primarily new and never used and carry a premium over [the] retail price.”

Taylor, 59, speaks with Penta about her company and the luxury resale market overall.

Can you talk about how the luxury resale market for handbags and jewelry has evolved in recent years, especially since the pandemic?

About three weeks into the pandemic, we started getting orders. They were slow at first but then accelerated.

With retail stores closed and travel restricted, people turned online to shop. The only place to purchase new Hermès and Chanel handbags was online and from dealers on the secondary market. They became comfortable with buying these brands online. Sales increased by 60% in 2020 and doubled in 2021, compared to the prior years. Even after the brand boutiques opened and travel resumed, online sales continued their momentum. Our sales quadrupled from 2019 to 2023.23.

Who are your customers, and have they changed over the years?

Our clients are primarily those who have disposable income and love to spend it on beautiful things. Partners of hedge funds, investment bankers and law firms, self-made entrepreneurs, physicians and dentists, celebrities and socialites represent the bulk. But we always have the aspiring—those for whom buying a Birkin or Kelly is a bit of a financial stretch.

What are the advantages of buying a resale bag or piece of jewellery?

Hermès and Chanel do not offer their handbags online. While Hermès.com may offer one or a few small bags on occasion, they are sold out in seconds. The same goes for branded jewellery, notably Van Cleef & Arpels. Try purchasing a popular VC&A Alhambra piece online or in one of their stores to take home immediately—it is almost impossible.

Madison Avenue Couture

The second is ease of purchase. Hermès has made getting a holy grail bag almost a “blood sport.” The machinations that someone goes through to get a Birkin or Kelly are anxiety-producing for most. First, you need to find a friendly sales associate. Then, a profile must be built, which involves spending on Hermès goods that are not leather handbags. The more the spend, the greater the chance of getting a handbag. Expensive furniture, fine jewelry, and watches have the greatest sway. Scarves or a pair of shoes won’t bat an eyelash. The amount needed to be spent is unknown, but we’ve heard it could be significantly more than the price of the bag. Plus, there is no guarantee that it will result in getting the bag of your dreams.

In the secondary market, you can pick the bag of your dreams without the hassle and stress of building a profile.

How do you source your items, and how are you able to guarantee their authenticity?

We purchase from individuals and other handbag dealers primarily. We usually get the original store receipt or a copy of it for most bags we purchase, which establishes provenance. Regardless of having the receipt or not, every bag goes through in-house and third-party authentication. We chose who we believe to be the best independent authenticators of Hermès and Chanel, which is where we find the most counterfeits.

What are some of the most in-demand brands and items for buyers who can afford them?

Hermès and Chanel handbags are generally in demand by professional and affluent women and men who give them as gifts. Goyard is popular because it evokes quiet luxury. In jewelry, we see the greatest demand is for Van Cleef & Arpels pieces, particularly the Alhambra series.

What advice do you have for people who want to find a specific piece from a source outside of the brand itself?

We recommend that people purchase only from dealers who guarantee authenticity and have a history of selling only authentic bags.

Furthermore, rely on a reseller that has its inventory on hand like us. We have already checked the condition, verified authenticity, and confirmed availability. Marketplaces, which aggregate different vendors, cannot know for certain if an item is available, in the stated condition or authentic. (Some authenticate after the item is sold, which delays getting the item.) Resellers that do not have an item in stock will source it, which can take weeks and may not be in the condition described.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

What a quarter-million dollars gets you in the western capital.

Alexandre de Betak and his wife are focusing on their most personal project yet.

Subsidised minivans, no income taxes: Countries have rolled out a range of benefits to encourage bigger families, with no luck

Imagine if having children came with more than $150,000 in cheap loans, a subsidised minivan and a lifetime exemption from income taxes.

Would people have more kids? The answer, it seems, is no.

These are among the benefits—along with cheap child care, extra vacation and free fertility treatments—that have been doled out to parents in different parts of Europe, a region at the forefront of the worldwide baby shortage. Europe’s overall population shrank during the pandemic and is on track to contract by about 40 million by 2050, according to United Nations statistics.

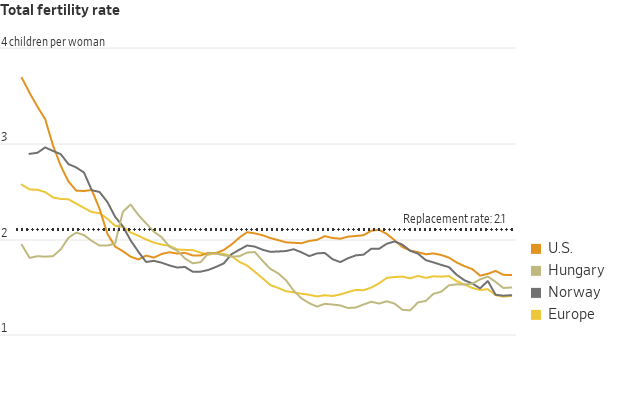

Birthrates have been falling across the developed world since the 1960s. But the decline hit Europe harder and faster than demographers expected—a foreshadowing of the sudden drop in the U.S. fertility rate in recent years.

Reversing the decline in birthrates has become a national priority among governments worldwide, including in China and Russia , where Vladimir Putin declared 2024 “the year of the family.” In the U.S., both Kamala Harris and Donald Trump have pledged to rethink the U.S.’s family policies . Harris wants to offer a $6,000 baby bonus. Trump has floated free in vitro fertilisation and tax deductions for parents.

Europe and other demographically challenged economies in Asia such as South Korea and Singapore have been pushing back against the demographic tide with lavish parental benefits for a generation. Yet falling fertility has persisted among nearly all age groups, incomes and education levels. Those who have many children often say they would have them even without the benefits. Those who don’t say the benefits don’t make enough of a difference.

Two European countries devote more resources to families than almost any other nation: Hungary and Norway. Despite their programs, they have fertility rates of 1.5 and 1.4 children for every woman, respectively—far below the replacement rate of 2.1, the level needed to keep the population steady. The U.S. fertility rate is 1.6.

Demographers suggest the reluctance to have kids is a fundamental cultural shift rather than a purely financial one.

“I used to say to myself, I’m too young. I have to finish my bachelor’s degree. I have to find a partner. Then suddenly I woke up and I was 28 years old, married, with a car and a house and a flexible job and there were no more excuses,” said Norwegian Nancy Lystad Herz. “Even though there are now no practical barriers, I realised that I don’t want children.”

The Hungarian model

Both Hungary and Norway spend more than 3% of GDP on their different approaches to promoting families—more than the amount they spend on their militaries, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

Hungary says in recent years its spending on policies for families has exceeded 5% of GDP. The U.S. spends around 1% of GDP on family support through child tax credits and programs aimed at low-income Americans.

Hungary’s subsidised housing loan program has helped almost 250,000 families buy or upgrade their homes, the government says. Orsolya Kocsis, a 28-year-old working in human resources, knows having kids would help her and her husband buy a larger house in Budapest, but it isn’t enough to change her mind about not wanting children.

“If we were to say we’ll have two kids, we could basically buy a new house tomorrow,” she said. “But morally, I would not feel right having brought a life into this world to buy a house.”

Promoting baby-making, known as pro natalism, is a key plank of Prime Minister Viktor Orbán ’s broader populist agenda . Hungary’s biennial Budapest Demographic Summit has become a meeting ground for prominent conservative politicians and thinkers. Former Fox News anchor Tucker Carlson and JD Vance, Trump’s vice president pick, have lauded Orbán’s family policies.

Orbán portrays having children inside what he has called a “traditional” family model as a national duty, as well as an alternative to immigration for growing the population. The benefits for child-rearing in Hungary are mostly reserved for married, heterosexual, middle-class couples. Couples who divorce lose subsidised interest rates and in some cases have to pay back the support.

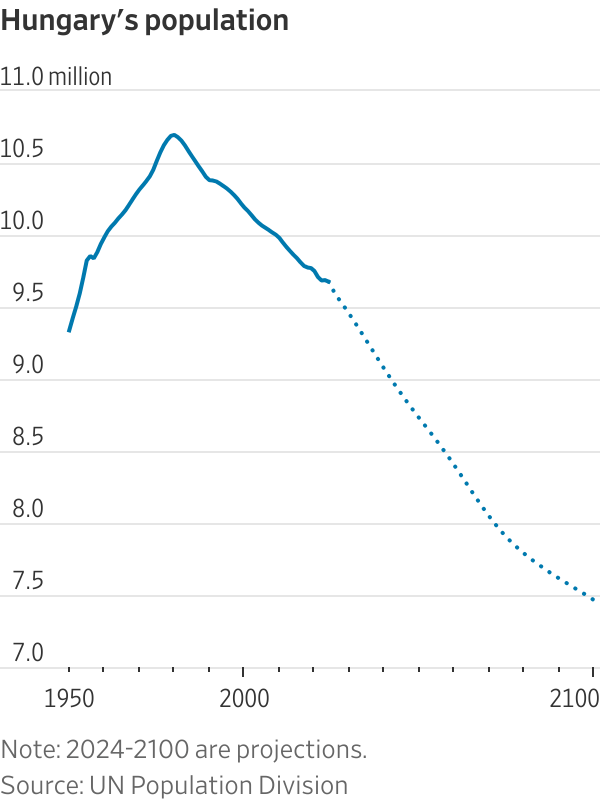

Hungary’s population, now less than 10 million, has been shrinking since the 1980s. The country is about the size of Indiana.

“Because there are so few of us, there’s always this fear that we are disappearing,” said Zsuzsanna Szelényi, program director at the CEU Democracy Institute and author of a book on Orbán.

Hungary’s fertility rate collapsed after the fall of the Soviet Union and by 2010 was down to 1.25 children for every woman. Orbán, a father of five, and his Fidesz party swept back into power that year after being ousted in the early 2000s. He expanded the family support system over the next decade.

Hungary’s fertility rate rose to 1.6 children for every woman in 2021. Ivett Szalma, an associate professor at Corvinus University of Budapest, said that like in many other countries, women in Hungary who had delayed having children after the global financial crisis were finally catching up.

Then progress stalled. Hungary’s fertility rate has fallen for the past two years. Around 51,500 babies have been born there this year through August, a 10% drop compared with the same period last year. Many Hungarian women cite underfunded public health and education systems and difficulties balancing work and family as part of their hesitation to have more children.

Anna Nagy, a 35-year-old former lawyer, had her son in January 2021. She received a loan of about $27,300 that she didn’t have to start paying back until he turned 3. Nagy had left her job before getting pregnant but still received government-funded maternity payments, equal to 70% of her former salary, for the first two years and a smaller amount for a third year.

She used to think she wanted two or three kids, but now only wants one. She is frustrated at the implication that demographic challenges are her responsibility to solve. Economists point to increased immigration and a higher retirement age as other offsets to the financial strains on government budgets from a declining population.

“It’s not our duty as Hungarian women to keep the nation alive,” she said.

Big families

Hungary is especially generous to families who have several children, or who give birth at younger ages. Last year, the government announced it would restrict the loan program used by Nagy to women under 30. Families who pledge to have three or more children can get more than $150,000 in subsidised loans. Other benefits include a lifetime exemption from personal taxes for mothers with four or more kids, and up to seven extra annual vacation days for both parents.

Under another program that’s now expired, nearly 30,000 families used a subsidy to buy a minivan, the government said.

Critics of Hungary’s family policies say the money is wasted on people who would have had large families anyway. The government has also been criticised for excluding groups such as the minority Roma population and poorer Hungarians. Bank accounts, credit histories and a steady employment history are required for many of the incentives.

Orbán’s press office didn’t respond to requests for comment. Tünde Fűrész, head of a government-backed demographic research institute, disagreed that the policies are exclusionary and said the loans were used more heavily in economically depressed areas.

Government programs weren’t a determining factor for Eszter Gerencsér, 37, who said she and her husband always wanted a big family. They have four children, ages 3 to 10.

They received about $62,800 in low-interest loans through government programs and $35,500 in grants. They used the money to buy and renovate a house outside of Budapest. After she had her fourth child, the government forgave $11,000 of the debt. Her family receives a monthly payment of about $40 a month for each child.

Most Hungarian women stay home with their children until they turn 2, after which maternity payments are reduced. Publicly run nurseries are free for large families like hers. Gerencsér worked on and off between her pregnancies and returned full-time to work, in a civil-service job, earlier this year.

She still thinks Hungarian society is stacked against mothers and said she struggled to find a job because employers worried she would have to take lots of time off.

The country’s international reputation as family-friendly is “what you call good marketing,” she said.

Nordic largesse

Norway has been incentivising births for decades with generous parental leave and subsidised child care. New parents in Norway can share nearly a year of fully paid leave, or around 14 months at 80% pay. More than three months are reserved for fathers to encourage more equal caregiving. Mothers are entitled to take at least an hour at work to breast-feed or pump.

The government’s goal has never been explicitly to encourage people to have more children, but instead to make it easier for women to balance careers and children, said Trude Lappegard, a professor who researches demography at the University of Oslo. Norway doesn’t restrict benefits for unmarried parents or same-sex couples.

Its fertility rate of 1.4 children per woman has steadily fallen from nearly 2 in 2009. Unlike Hungary, Norway’s population is still growing for now, due mostly to immigration.

“It is difficult to say why the population is having fewer children,” Kjersti Toppe, the Norwegian Minister of Children and Families, said in an email. She said the government has increased monthly payments for parents and has formed a committee to investigate the baby bust and ways to reverse it.

More women in Norway are childless or have only one kid. The percentage of 45-year-old women with three or more children fell to 27.5% last year from 33% in 2010. Women are also waiting longer to have children—the average age at which women had their first child reached 30.3 last year. The global surge in housing costs and a longer timeline for getting established in careers likely plays a role, researchers say. Older first-time mothers can face obstacles: Women 35 and older are at higher risk of infertility and pregnancy complications.

Gina Ekholt, 39, said the government’s policies have helped offset much of the costs of having a child and allowed her to maintain her career as a senior adviser at the nonprofit Save the Children Norway. She had her daughter at age 34 after a round of state-subsidised IVF that cost about $1,600. She wanted to have more children but can’t because of fertility issues.

She receives a monthly stipend of about $160 a month, almost fully offsetting a $190 monthly nursery fee.

“On the economy side, it hasn’t made a bump. What’s been difficult for me is trying to have another kid,” she said. “The notion that we should have more kids, and you’re very selfish if you have only had one…those are the things that took a toll on me.”

Her friend Ewa Sapieżyńska, a 44-year-old Polish-Norwegian writer and social scientist with one son, has helped her see the upside of the one-child lifestyle. “For me, the decision is not about money. It’s about my life,” she said.