WHERE CEOS FIND TIME FOR TRIATHLON TRAINING AND MOTORCYCLE RACING

Leaders with epic hobbies seem to squeeze more hours out of the day than the rest of us

Leaders with epic hobbies seem to squeeze more hours out of the day than the rest of us

Many of us can barely keep up with our jobs, never mind hobbies. Yet some top executives run marathons, wineries or music-recording studios on the side. How can they have bigger responsibilities and more fun than we do?

It can seem like ultrahigh achievers find extra hours in the day. They say they’ve just figured out how to manage their 24 better than the rest of us.

They also admit they take full advantage of the privileges of being a boss—the power to delegate and the means to do things like jetting to Denmark for a long weekend of windsurfing.

Dan Streetman trains as many as 20 hours a week for Ironman triathlons in addition to his job as CEO of cybersecurity firm Tanium. It’s a big commitment for anyone, never mind a corporate leader who travels to meet with customers every week. He pulls it off by sleeping fewer than seven hours a night and waking around 5 a.m., planning his exercise sessions months in advance, and switching his brain from work mode to sport mode almost as fast as he transitions from swimming to cycling during a competition.

“I tend to work right up until the day of the race,” says Streetman, 56 years old. “I remember being on a board call on a Friday night, and Saturday morning was an Ironman. That’s just part of it.”

Ahead of business trips, he maps running routes in unfamiliar cities and scouts nearby pools, often at YMCAs. He rides stationary bikes in hotel gyms and, if they’re subpar, makes a note to book somewhere else next time he’s in town.

Leaders who eat, breathe and sleep business can appear out of touch at a time when employees crave work-life balance and expect their bosses to model it. Today’s prototypical CEO has a full life outside of work, or at least the appearance of one.

Their tactics include waking up early, multitasking and scheduling fun as if it were any other appointment. When you’re a top executive, hobbies tend to disappear unless they’re on the calendar. One CEO told me he disguises “me time” as important meetings. Only his assistant knows which calendar blocks are fake.

Ben Betts calls himself a “spreadsheet guy,” which is a bit like saying Michelangelo was a paint guy. With Excel as his canvas, Betts creates cell-by-cell checklists for just about everything he does, from cooking Christmas dinner to building a coop for newly hatched ducklings.

Betts, 41, is CEO of Learning Pool, a professional-development software maker. The duck home is part of his ambitious effort to restore an 18th-century farmhouse in England. He’s been renovating for about five years and aims to finish this fall.

On a recent Saturday, Betts’s spreadsheet called for stripping overhead beams by 5 p.m. so he could refinish them. Otherwise, the task would have to wait until the following weekend, throwing off his whole timeline. His vision of the home as a cozy enclave—completed in time for the holidays—can only come true if he sticks to a precise plan.

“Sometimes I stand in the doorway, and my wife probably wonders what I’m staring at,” he says. “I’m picturing us on a corner sofa with our two kids and the dog, watching a film in front of the fireplace I installed.”

John Sicard , president and CEO of supply-chain manager Kinaxis , got back into drumming many years after he let go of his dream to become a professional musician. He practices almost every day, but his sessions sometimes last only 20 minutes. He rehearses with bandmates two or three times a month. That’s enough to prepare Sicard, 61, to play Foo Fighters and Led Zeppelin covers at occasional charity gigs.

He also built a studio in his house, where he records up-and-coming artists. He finds time by sticking to this management philosophy: “The most successful CEOs do the least amount of work.”

For Sicard, that means letting his lieutenants take charge of—and responsibility for—their divisions. Many corporate leaders work harder than they need to because they micromanage or hire poorly and pick up the slack, he says.

Thomas Hansen , president of software maker Amplitude, is back to windsurfing, a sport he competed in as a teenager. He lives near the ocean in California but gets out on the water only about once a month, when the waves are just right. Hobbies don’t need to be daily activities to be fulfilling, he says, especially if they require training regimens.

To stay in shape for windsurfing, he rises at 4:30 a.m., seven days a week, for an hour of exercise. Hansen, 54, also guards his Saturdays and Sundays like the crown jewels of Denmark, his native country, limiting himself to two working weekends a year. Things that feel urgent can almost always wait till Monday, he contends.

When Christine Yen isn’t calling the shots at work, she’s circling a racetrack at 80 mph on her Honda CB300F motorcycle. The co-founder and CEO of Honeycomb, which helps engineers diagnose problems in their software, took up racing a few years ago.

Prepandemic, her motorcycle was strictly for commuting in San Francisco—and making an impression. She loved pulling up to investor meetings in her hornet-yellow helmet and leather riding suit.

“It fits me like a glove, and it makes me feel like a badass,” says Yen, 36.

The keys to spending full days at the track are planning and being willing to work at odd hours, Yen discovered. Her favorite track publishes racing schedules in 10-week batches. As soon as a slate is released, she circles the dates when she expects her workload will be lightest, aiming to participate in roughly half of the events.

“I have also been known to bring my laptop to the motel and get some work done in the evenings,” she says. “It sounds boring to say hobbies can be scheduled, but that’s how I protect my time.”

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

What a quarter-million dollars gets you in the western capital.

Alexandre de Betak and his wife are focusing on their most personal project yet.

Report by the San Francisco Fed shows small increase in premiums for properties further away from the sites of recent fires

Wildfires in California have grown more frequent and more catastrophic in recent years, and that’s beginning to reflect in home values, according to a report by the San Francisco Fed released Monday.

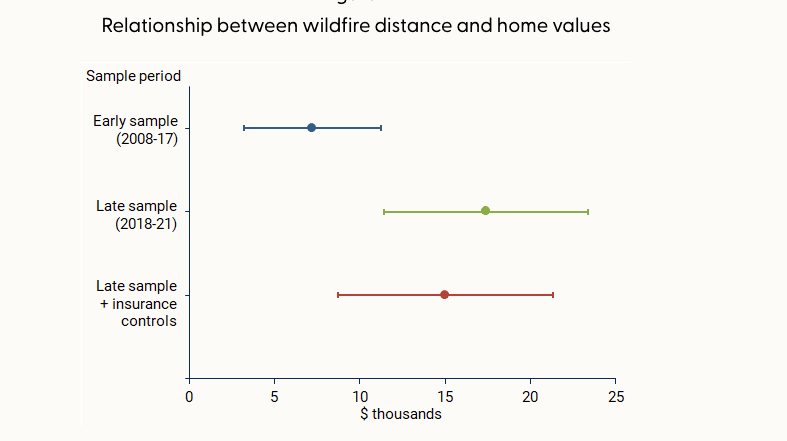

The effect on home values has grown over time, and does not appear to be offset by access to insurance. However, “being farther from past fires is associated with a boost in home value of about 2% for homes of average value,” the report said.

In the decade between 2010 and 2020, wildfires lashed 715,000 acres per year on average in California, 81% more than the 1990s. At the same time, the fires destroyed more than 10 times as many structures, with over 4,000 per year damaged by fire in the 2010s, compared with 355 in the 1990s, according to data from the United States Department of Agriculture cited by the report.

That was due in part to a number of particularly large and destructive fires in 2017 and 2018, such as the Camp and Tubbs fires, as well the number of homes built in areas vulnerable to wildfires, per the USDA account.

The Camp fire in 2018 was the most damaging in California by a wide margin, destroying over 18,000 structures, though it wasn’t even in the top 20 of the state’s largest fires by acreage. The Mendocino Complex fire earlier that same year was the largest ever at the time, in terms of area, but has since been eclipsed by even larger fires in 2020 and 2021.

As the threat of wildfires becomes more prevalent, the downward effect on home values has increased. The study compared how wildfires impacted home values before and after 2017, and found that in the latter period studied—from 2018 and 2021—homes farther from a recent wildfire earned a premium of roughly $15,000 to $20,000 over similar homes, about $10,000 more than prior to 2017.

The effect was especially pronounced in the mountainous areas around Los Angeles and the Sierra Nevada mountains, since they were closer to where wildfires burned, per the report.

The study also checked whether insurance was enough to offset the hit to values, but found its effect negligible. That was true for both public and private insurance options, even though private options provide broader coverage than the state’s FAIR Plan, which acts as an insurer of last resort and provides coverage for the structure only, not its contents or other types of damages covered by typical homeowners insurance.

“While having insurance can help mitigate some of the costs associated with fire episodes, our results suggest that insurance does little to improve the adverse effects on property values,” the report said.

While wildfires affect homes across the spectrum of values, many luxury homes in California tend to be located in areas particularly vulnerable to the threat of fire.

“From my experience, the high-end homes tend to be up in the hills,” said Ari Weintrub, a real estate agent with Sotheby’s in Los Angeles. “It’s up and removed from down below.”

That puts them in exposed, vegetated areas where brush or forest fires are a hazard, he said.

While the effect of wildfire risk on home values is minimal for now, it could grow over time, the report warns. “This pattern may become stronger in years to come if residential construction continues to expand into areas with higher fire risk and if trends in wildfire severity continue.”