General Motors shook up the car industry this past week, saying it is aiming to stop selling gasoline-powered cars by 2035, much sooner than many on Wall Street would have predicted.

It is a sign that analysts and investors should be sharpening their pencils to figure out what is likely—and what is possible—for global electric-vehicle demand. The results of that number crunching will help to show whether the market has valued highflying EV stocks correctly and which, if any, still offer good value.

It isn’t an easy equation to solve. Auto makers express their goals—one indication of what might happen in the market—in different ways.

General Motors (ticker: GM) has its target for 2035. Tesla (TSLA) CEO Elon Musk has talked about selling 20 million EVs by 2030 and plans to increase its production volume at 50% a year for the foreseeable future.

Volkswagen (VOW. Germany) wants up to 25% of vehicle sales to come from battery-powered electric vehicles by 2030. And Toyota (TM) plans to sell 5.5 million electrified vehicles by 2030—a figure that includes hybrid electric cars as well as fuel-cell vehicles.

Barron’s added up the numbers in the publicly announced goals, aligning them by year and filling in some gaps. We calculate that, based on company comments, somewhere between 15 million and 20 million EVs will be sold a year by 2025. That implies an average annual growth rate of about 50% between last year and then. With that growth, EVs would account for roughly 15% to 20% of total light-vehicle sales.

Wedbush analyst Dan Ives qualifies as an electric-vehicle bull, but his estimate of EVs’ share of the market isn’t that high. “I am laser-focused on the skyrocketing EV demand out of China, Biden green initiatives, and [battery innovation] across the EV supply chain,” he tells Barron’s. “It looks like a golden age for EVs.”

Still, he is assuming EVs will win about 10% of the global market by 2025.

Focusing on China is a good idea. It’s the largest new-car market in the world and government incentives make buying an EV a “no brainer” for most consumers, according to Ives. Goldman Sachs analyst Fei Fang has predicted EVs will have 20% of the Chinese market by 2025.

RBC analyst Joseph Spak recently projected battery- and hybrid-electric vehicles could account for roughly 15% of new-car sales by 2025. That call was made back in December, before GM announced its aspiration to be all-electric by 2035.

Now Spak believes his projection could be too low. He did his own math to illustrate why.

“GM historically has had [about] 17% total U.S. market share,” he wrote in a recent research note. In December, he expected EVs to account for 40% of U.S. new-car sales by 2035. But for GM to go all-electric by then, assuming it keeps its historic 17% of the market, it would have to win 43% of U.S. EV sales, he said.

“The other way to interpret this [math] is that there could be upside to our 40% [battery electric] mix assumption,” added the analyst. That would be bullish for EV stocks, but he has a word of caution too. “A massive ramp in battery supply is needed to support this,” he said.

That gets at another important point for investors. There are many tertiary effects from faster EV penetration.

For one, as EVs take a bigger share of the market, they will start to get more of the capital the industry is willing to spend on product development. GM, for instance, is spending about half its capital over the next few years on EV and autonomous-driving technologies. By 2030, cars powered by internal combustion engines—ICE cars, in industry jargon—won’t look as attractive, relatively speaking, as those programs are drained of resources.

Electricity infrastructure is another critical issue. Right now oil and the refining industry essentially power cars. In the future, utilities and the electric grid will bear the burden.

The math needed to predict global electricity demand is harder, but higher EV penetration in 2025 would probably boost growth, now at roughly 3% a year, by a couple of percentage points. That seems manageable, but it means more investment in utilities.

The other side off the electricity equation is oil. Oil demand could fall slightly compared with 2019, a pre-pandemic year, if the world’s pool of EVs grows faster than expected. There are roughly 2 billion light vehicles on the road and nearly all take gasoline.

The next step in this math class is to value the EV sector. That isn’t easy either.

Given the growth and accelerating penetration, figures for 2025, when EV companies should be making real money, seem like a reasonable place to start. Apple (AAPL), the world’s most valuable company, trades for about 19 times estimated 2025 cash flow of about $120 billion.

Tesla is trading for about 65 times estimated 2025 cash flows. That is triple the figure for Apple, although if Musk’s goals are met, Tesla’s annual sales will go from more than 4 million vehicles to about 20 million over the next five years—between 2025 and 2030.

China’s NIO (NIO) is another highly valued EV stock. Analysts haven’t made public projections for its 2025 financials. But its shares trade for about 30 times estimated 2024 cash flow. According to analysts, NIO vehicle shipments are expected to go from roughly 345,000 to about 800,00 from 2025 to 2030. That is less growth than Tesla is looking to produce, but it still implies sales would more than double.

The 2025 valuation math can’t tell investors to buy or sell the stock, or the sector, but it does offer context about the coming golden age of EVs. Tesla stock is up about 21% year to date. NIO shares are up almost 19%. The S&P 500 is up about 2%.

Investors expect a lot. Morgan Stanley’s Adam Jonas pointed out that January EV sales in the U.S. were still less than 3% of the total, but he isn’t an EV bear. He rates Tesla stock at Buy and has a target of $880 for the stock-price target.

The ICE Age is ending. If the switch to EVs is rapid, valuations for manufacturers might not be unreasonable. The effects on other industries are just starting to be felt.

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

Copyright 2020, Dow Jones & Company, Inc. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. LEARN MORE

What a quarter-million dollars gets you in the western capital.

Alexandre de Betak and his wife are focusing on their most personal project yet.

Report by the San Francisco Fed shows small increase in premiums for properties further away from the sites of recent fires

Wildfires in California have grown more frequent and more catastrophic in recent years, and that’s beginning to reflect in home values, according to a report by the San Francisco Fed released Monday.

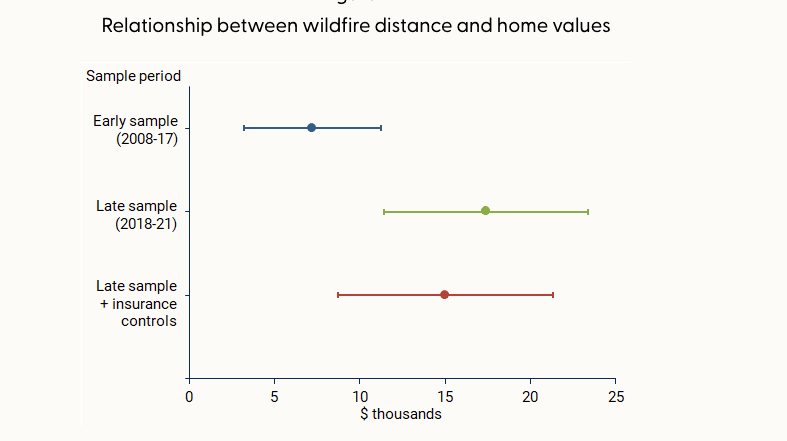

The effect on home values has grown over time, and does not appear to be offset by access to insurance. However, “being farther from past fires is associated with a boost in home value of about 2% for homes of average value,” the report said.

In the decade between 2010 and 2020, wildfires lashed 715,000 acres per year on average in California, 81% more than the 1990s. At the same time, the fires destroyed more than 10 times as many structures, with over 4,000 per year damaged by fire in the 2010s, compared with 355 in the 1990s, according to data from the United States Department of Agriculture cited by the report.

That was due in part to a number of particularly large and destructive fires in 2017 and 2018, such as the Camp and Tubbs fires, as well the number of homes built in areas vulnerable to wildfires, per the USDA account.

The Camp fire in 2018 was the most damaging in California by a wide margin, destroying over 18,000 structures, though it wasn’t even in the top 20 of the state’s largest fires by acreage. The Mendocino Complex fire earlier that same year was the largest ever at the time, in terms of area, but has since been eclipsed by even larger fires in 2020 and 2021.

As the threat of wildfires becomes more prevalent, the downward effect on home values has increased. The study compared how wildfires impacted home values before and after 2017, and found that in the latter period studied—from 2018 and 2021—homes farther from a recent wildfire earned a premium of roughly $15,000 to $20,000 over similar homes, about $10,000 more than prior to 2017.

The effect was especially pronounced in the mountainous areas around Los Angeles and the Sierra Nevada mountains, since they were closer to where wildfires burned, per the report.

The study also checked whether insurance was enough to offset the hit to values, but found its effect negligible. That was true for both public and private insurance options, even though private options provide broader coverage than the state’s FAIR Plan, which acts as an insurer of last resort and provides coverage for the structure only, not its contents or other types of damages covered by typical homeowners insurance.

“While having insurance can help mitigate some of the costs associated with fire episodes, our results suggest that insurance does little to improve the adverse effects on property values,” the report said.

While wildfires affect homes across the spectrum of values, many luxury homes in California tend to be located in areas particularly vulnerable to the threat of fire.

“From my experience, the high-end homes tend to be up in the hills,” said Ari Weintrub, a real estate agent with Sotheby’s in Los Angeles. “It’s up and removed from down below.”

That puts them in exposed, vegetated areas where brush or forest fires are a hazard, he said.

While the effect of wildfire risk on home values is minimal for now, it could grow over time, the report warns. “This pattern may become stronger in years to come if residential construction continues to expand into areas with higher fire risk and if trends in wildfire severity continue.”